The American Promise:

Printed Page 640

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 600

The Great Migrations of African Americans and Mexicans

Before the Red scare lost steam, the government raised alarms about the loyalty of African Americans. A Justice Department investigation concluded that Reds were fomenting racial unrest among blacks. Although the report was wrong about Bolshevik influence, it was correct in noticing a new stirring among African Americans.

In 1900, nine of every ten blacks still lived in the South, where poverty, disfranchisement, segregation, and violence dominated their lives. A majority of black men worked as dirt-

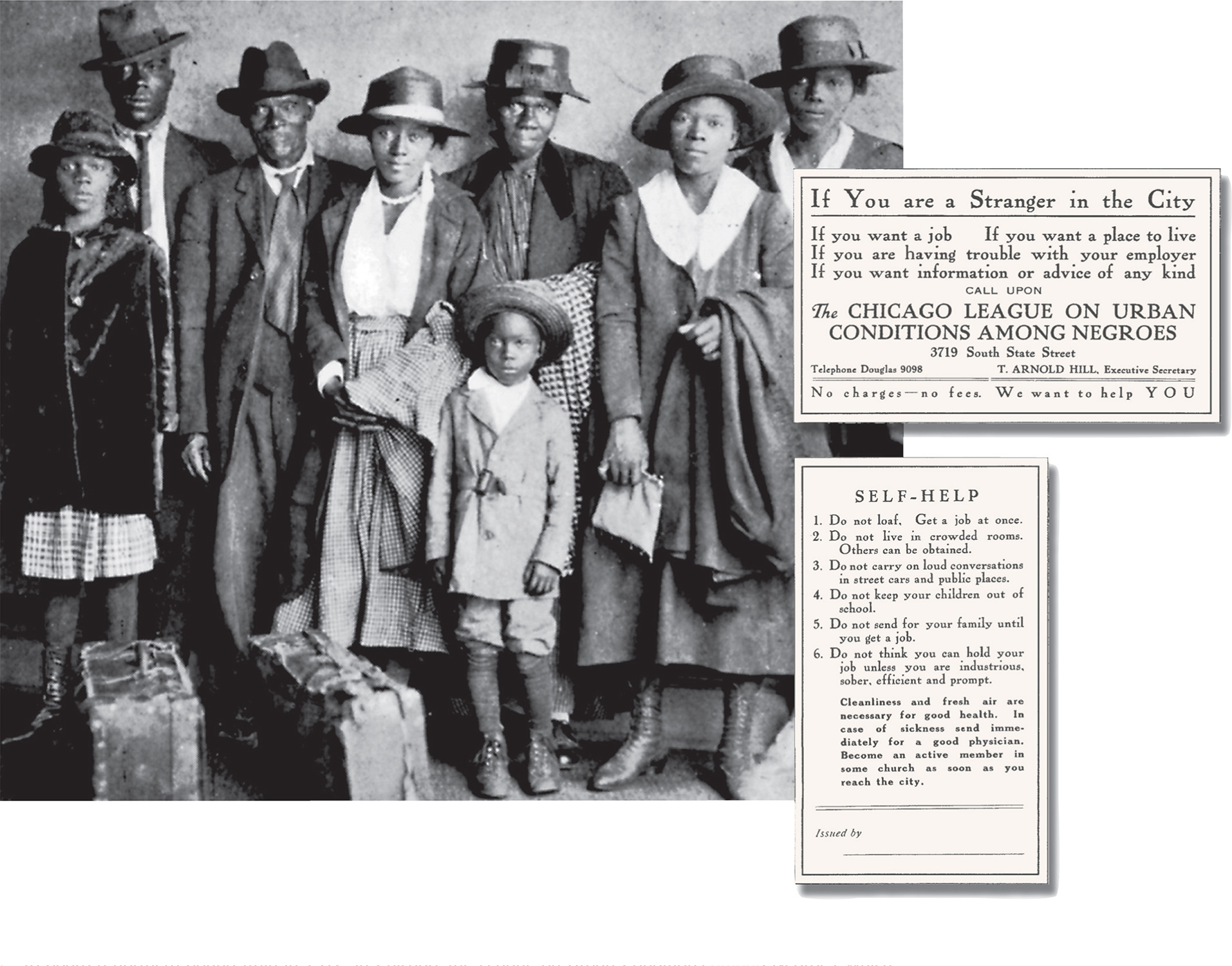

The First World War provided African Americans with the opportunity to escape the South’s cotton fields and kitchens. When war channeled almost 5 million American workers into military service and almost ended European immigration, northern industrialists turned to black labor. Black men found work in northern steel mills, shipyards, munitions plants, railroad yards, automobile factories, and mines. From 1915 to 1920, a half million blacks (approximately 10 percent of the South’s black population) boarded trains bound for Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, and other industrial cities.

Thousands of migrants wrote home to tell family and friends about their experiences in the North. One man announced proudly that he had recently been promoted to “first assistant to the head carpenter.” He added, “I should have been here twenty years ago. I just begin to feel like a man. . . .

But the North was not the promised land. Black men stood on the lowest rungs of the labor ladder. Jobs of any kind proved scarce for black women, and most worked as domestic servants as they did in the South. The existing black middle class sometimes shunned the less educated, less sophisticated rural southerners crowding into northern cities. Many whites, fearful of losing jobs and status, lashed out against the new migrants. Savage race riots ripped through two dozen northern cities. The worst occurred in July 1917 when a mob of whites invaded a section of East St. Louis, Illinois, and murdered 39 people. In 1918, the nation witnessed 96 lynchings of blacks, some of them decorated war veterans still in uniform.

Still, most black migrants stayed in the North and encouraged friends and family to follow. By 1940, more than one million blacks had left the South, profoundly changing their own lives and the course of the nation’s history. Black enclaves such as Harlem in New York and the South Side of Chicago, “cities within cities,” emerged in the North. These assertive communities provided a foundation for black protest and political organization in the years ahead.

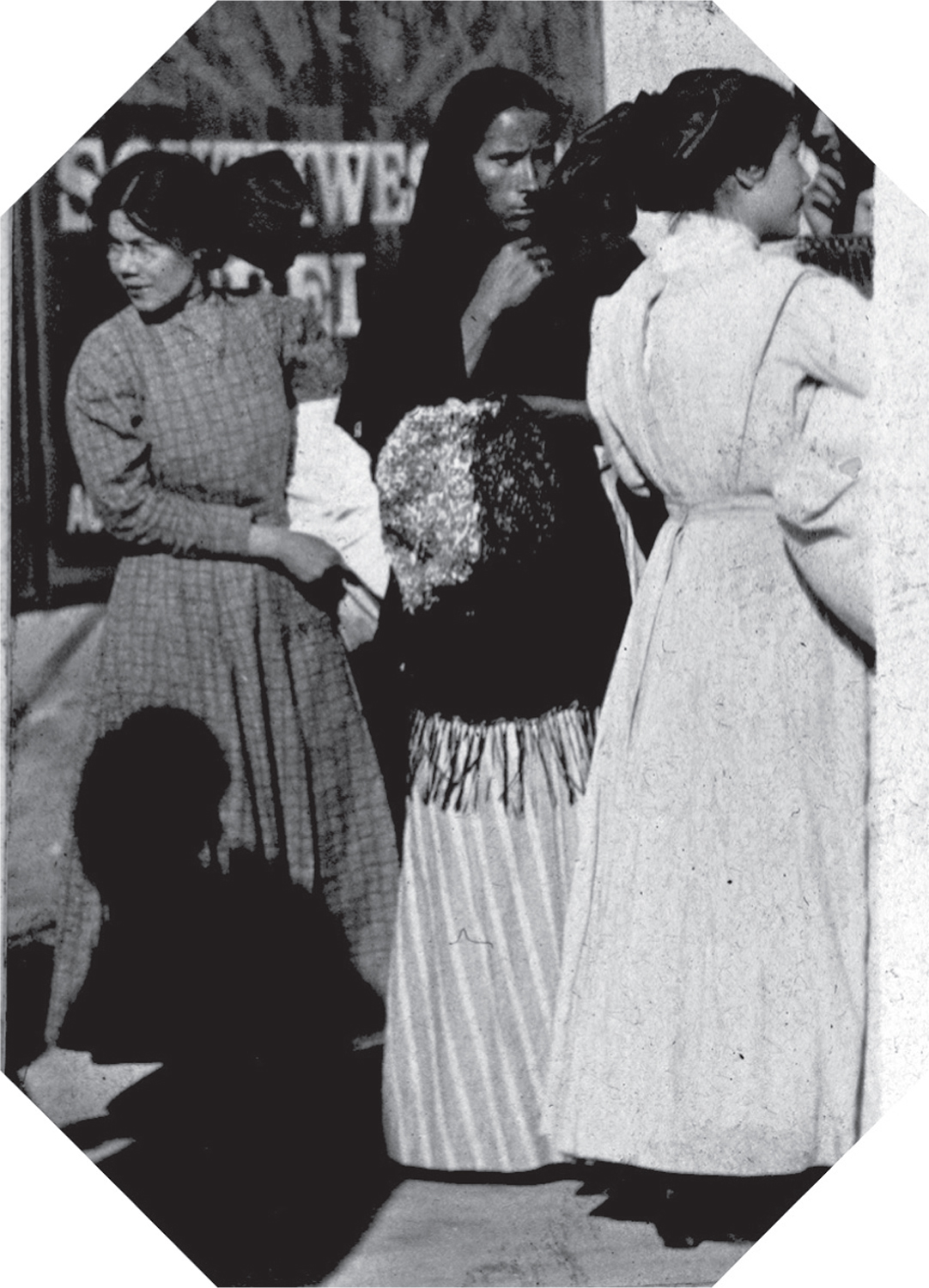

At nearly the same time, another migration was under way in the American Southwest. Between 1910 and 1920, the Mexican-

Like immigrants from Europe and black migrants from the South, Mexicans in the American Southwest dreamed of a better life. And like the others, they found both opportunity and disappointment. Wages were better than in Mexico, but life in the fields, mines, and factories was hard, and living conditions—

Among Mexican Americans, some of whom had lived in the Southwest for more than a century, los recién llegados (the recent arrivals) encountered mixed reactions. One Mexican American expressed this ambivalence: “We are all Mexicans anyway because the gueros [Anglos] treat us all alike.” But he also called for immigration quotas because the recent arrivals drove down wages and incited white prejudice that affected all ethnic Mexicans.

Despite friction, large-