The American Promise:

Printed Page 671

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 629

Working-Class Militancy

The nation’s working class bore the brunt of the economic collapse. By 1931, William Green, head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), had turned militant. “I warn the people who are exploiting the workers,” he shouted, “that they can drive them only so far before they will turn on them and destroy them. They are taking no account of the history of nations in which governments have been overturned. Revolutions grow out of the depths of hunger.”

The American people were slow to anger, but on March 7, 1932, several thousand unemployed autoworkers massed at the gates of Henry Ford’s River Rouge factory in Dearborn, Michigan, to demand work. Pelted with rocks, Ford’s private security forces responded with gunfire, killing four demonstrators. Forty thousand outraged citizens turned out for the unemployed men’s funerals.

Farmers mounted uprisings of their own. When Congress refused to guarantee farm prices, several thousand farmers created the National Farmers’ Holiday Association in 1932, so named because its members planned to take a “holiday” from shipping crops to market. Farm militants also resorted to what they called “penny sales.” When banks foreclosed and put farms up for auction, neighbors warned others not to bid, bought the foreclosed property for a few pennies, and returned it to the bankrupt owners. Militancy won farmers little in the way of long-

Even those who had proved their patriotism by serving in World War I rose up in protest against the government. In 1932, tens of thousands of unemployed veterans traveled to Washington, D.C., to petition Congress for the immediate payment of the pension (known as a “bonus”) that Congress had promised them in 1924. Hoover feared that the veterans would spark a riot and ordered the U.S. Army to evict the Bonus Marchers from their camp on the outskirts of the city. Tanks destroyed the squatters’ encampments while five hundred soldiers wielding bayonets and tear gas sent the protesters fleeing. The spectacle of the army driving peaceful, petitioning veterans from the nation’s capital further undermined public support for the beleaguered Hoover.

The Great Depression—

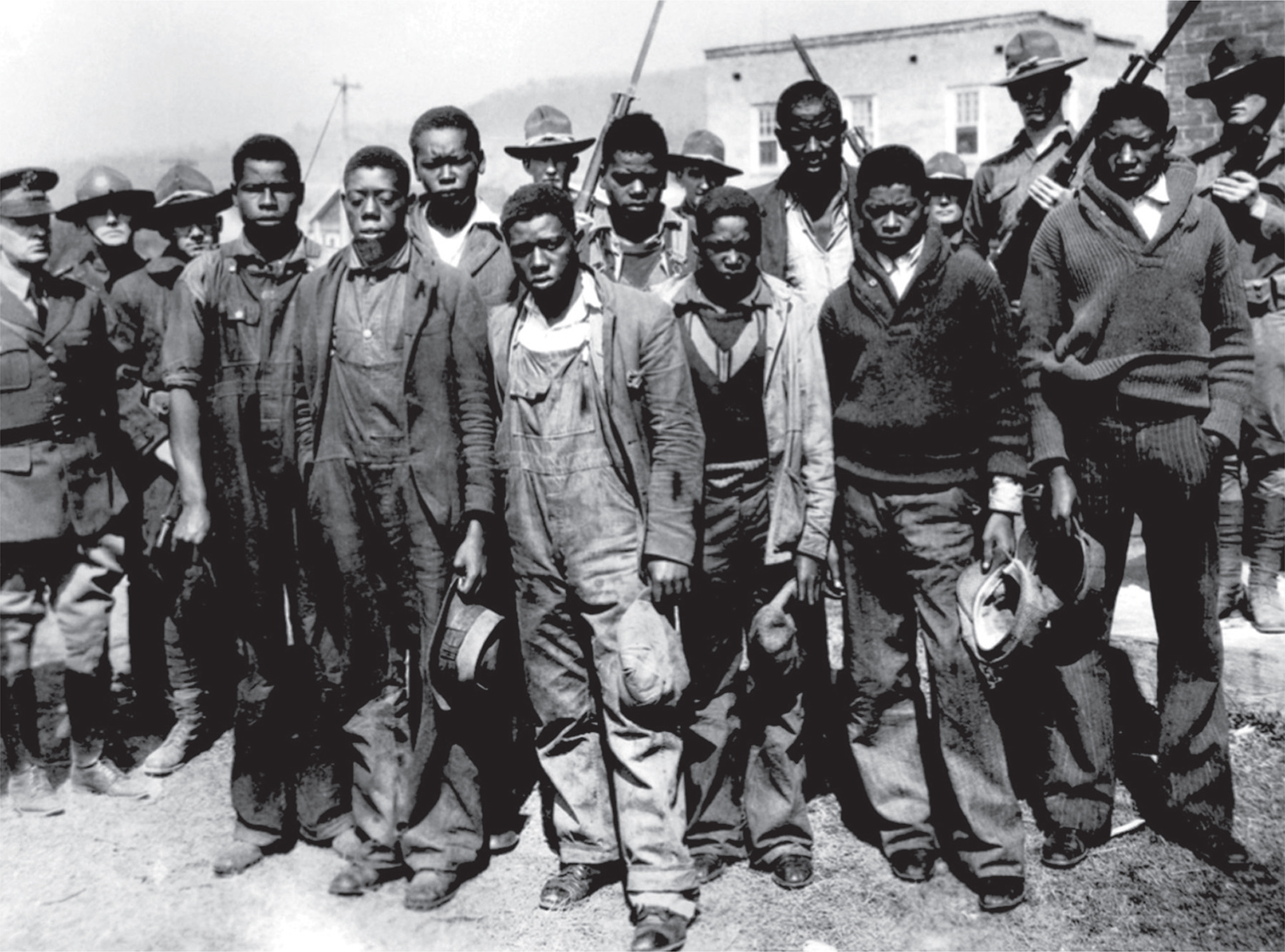

The left also led the fight against racism. While both major parties refused to challenge segregation in the South, the Socialist Party, led by Norman Thomas, attacked the system of sharecropping that left many African Americans in near servitude. The Communist Party also took action. When nine young black men in Scottsboro, Alabama (the Scottsboro Boys), were arrested on trumped-

Radicals on the left often sparked action, but protests by moderate workers and farmers occurred on a far greater scale. Breadlines, soup kitchens, foreclosures, unemployment, government violence, and cold despair drove patriotic men and women to question American capitalism. “I am as conservative as any man could be,” a Wisconsin farmer explained, “but any economic system that has in its power to set me and my wife in the streets, at my age—

REVIEW How did the depression reshape American politics?