The American Promise:

Printed Page 649

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 611

Automobiles, Mass Production, and Assembly-Line Progress

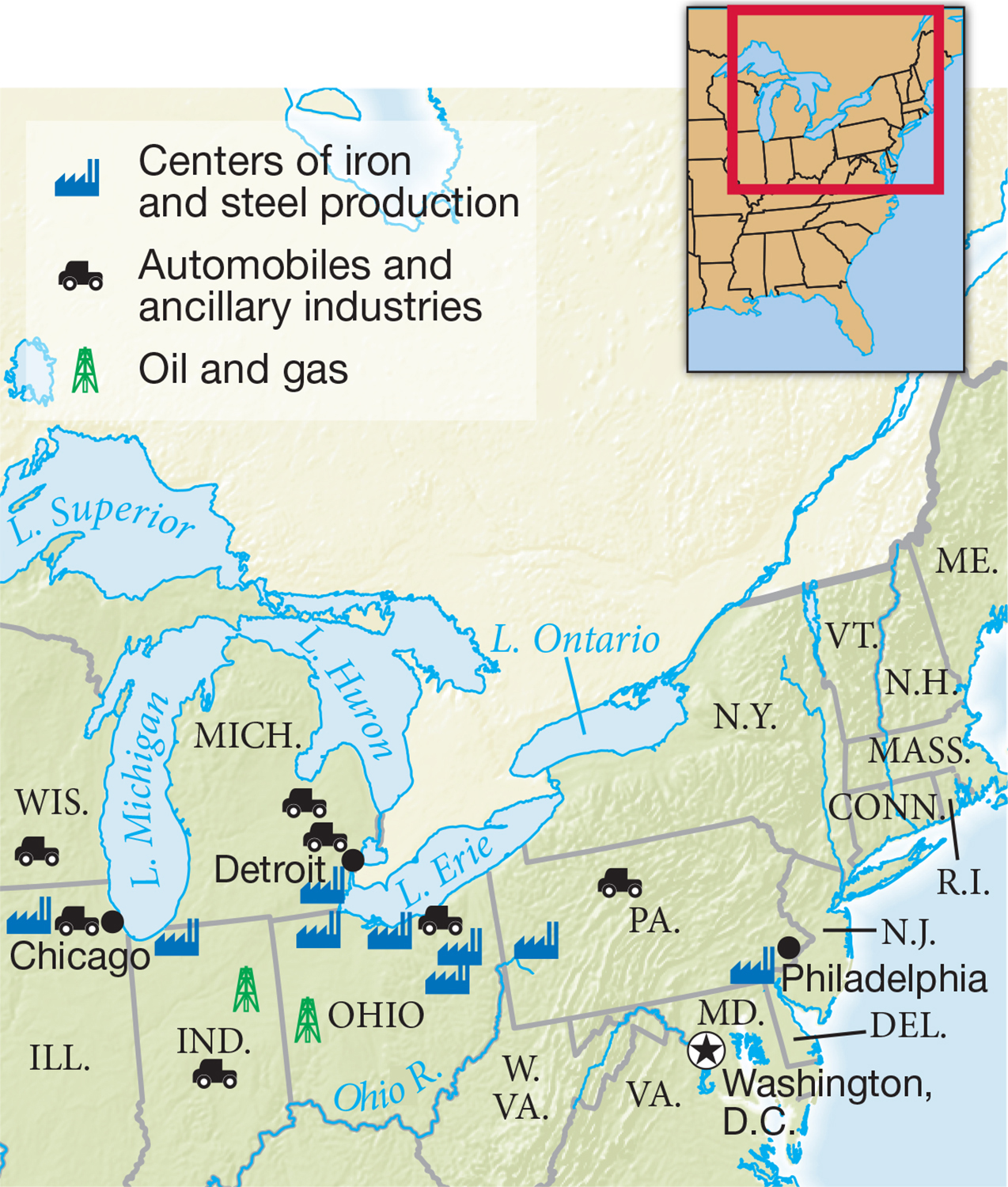

The automobile industry emerged as the largest single manufacturing industry in the nation. Henry Ford shrewdly located his company in Detroit, knowing that key materials for his automobiles were manufactured in nearby states (see Map 23.1). Keystone of the American economy, the automobile industry not only employed hundreds of thousands of workers directly but also brought whole industries into being—

Automobiles changed where people lived, what work they did, how they spent their leisure, even how they thought. Hundreds of small towns decayed because the automobile enabled rural people to bypass them in favor of more distant cities and towns. In cities, streetcars began to disappear as workers moved to the suburbs and commuted to work along crowded highways. Nothing shaped modern America more than the automobile, and efficient mass production made the automobile revolution possible.

Mass production by the assembly-

Industries also developed programs for workers that came to be called welfare capitalism. Some businesses improved safety and sanitation inside factories. They also instituted paid vacations and pension plans. Welfare capitalism encouraged loyalty to the company and discouraged traditional labor unions. One labor organizer in the steel industry bemoaned the success of welfare capitalism. “So many workmen here had been lulled to sleep by the company union, the welfare plans, the social organizations fostered by the employer,” he declared, “that they had come to look upon the employer as their protector, and had believed vigorous trade union organization unnecessary for their welfare.”