The American Promise:

Printed Page 690

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 646

Chapter Chronology

Casualties in the Countryside

The AAA weathered critical battering by champions of the old order better than the NRA. Allotment checks for keeping land fallow and crop prices high created loyalty among farmers with enough acreage to participate. As a white farmer in North Carolina declared, “I stand for the New Deal and Roosevelt . . . , the AAA . . . and crop control.”

Evicted Sharecroppers The New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Administration maintained farm prices by reducing acreage in production often resulted in the eviction of tenant farmers when the land they worked was left idle. These African American sharecroppers protested AAA policies that caused cotton farmers to evict them from their homes. They were among the many rural laborers whose lives were made worse by New Deal agricultural policies. © Bettmann/Corbis.

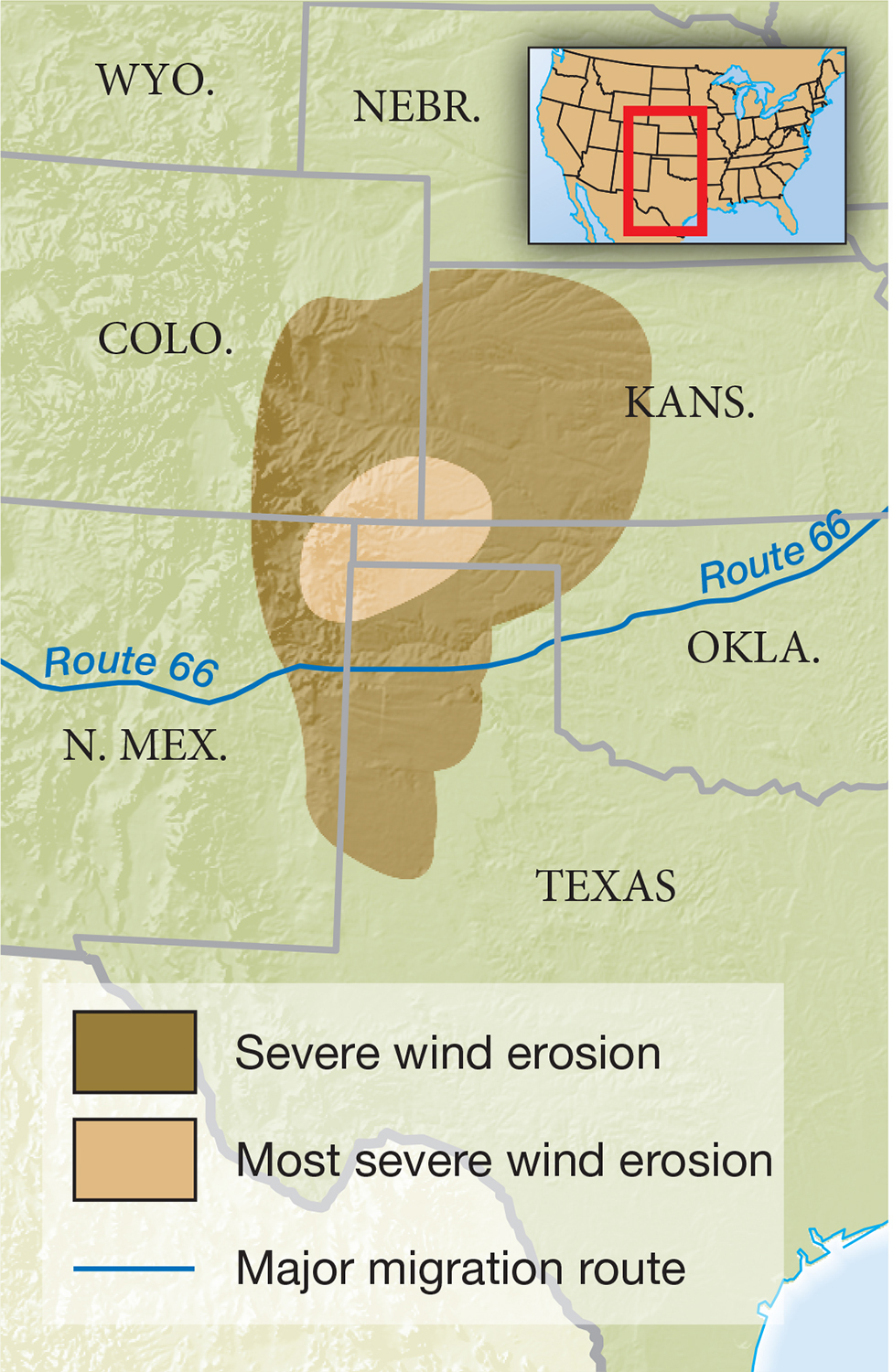

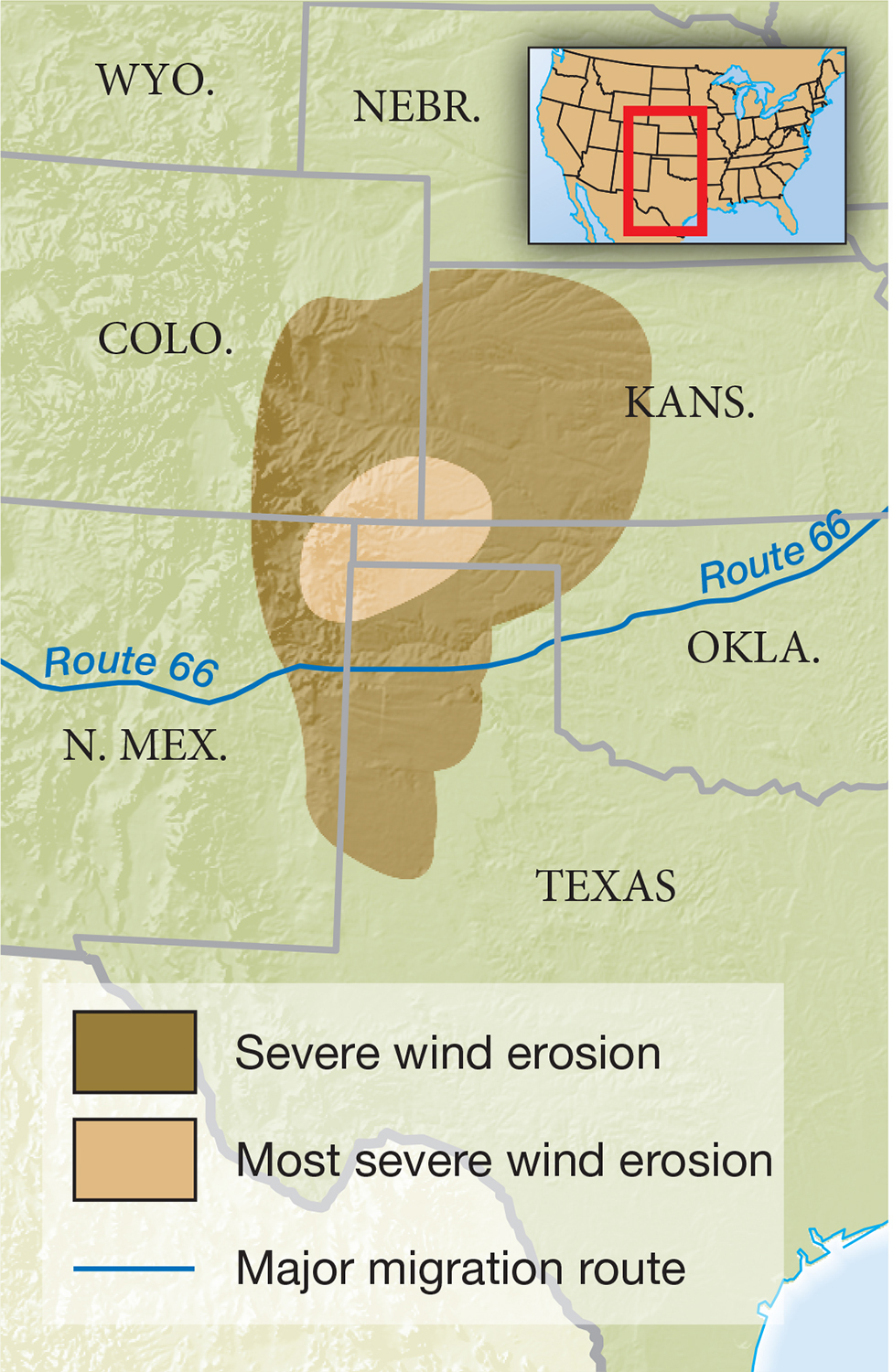

The Dust Bowl

Protests stirred, however, among those who did not qualify for allotments. The Southern Farm Tenants Union argued passionately that the AAA enriched large farmers while it impoverished small farmers who rented rather than owned their land. One black share-cropper explained why only $75 a year from New Deal agricultural subsidies trickled down to her: “De landlord is landlord, de politicians is landlord, de judge is landlord, de shurf [sheriff] is landlord, ever’body is landlord, en we [sharecroppers] ain’ got nothin’!” Like the NRA, the AAA tended to help most those who least needed help. Roosevelt’s political dependence on southern Democrats caused him to avoid confronting economic and racial inequities in the South.

Displaced tenants often joined the army of migrant workers like Florence Owens who straggled across rural America during the 1930s, some to flee Great Plains dust storms. Many migrants came from Mexico to work Texas cotton, Michigan beans, Idaho sugar beets, and California crops of all kinds. But since the number of people willing to take agricultural jobs usually exceeded the number of jobs available, wages fell and native-born white migrants fought to reserve even these low-wage jobs for themselves. Hundreds of thousands of “Okies” streamed out of the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, and Colorado, where chronic drought and harmful agricultural practices blasted crops and hopes. Parched, poor, and windblown, Okies—like the Joad family immortalized in John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939)—migrated to the lush fields and orchards of California, congregating in labor camps and hoping to find work and a future. But migrant laborers seldom found steady or secure work. As one Okie said, “When they need us they call us migrants, and when we’ve picked their crop, we’re bums and we got to get out.”