The American Promise:

Printed Page 776

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 722

Chapter Chronology

The Nuclear Arms Race

While Eisenhower moved against perceived Communist inroads abroad, he also sought to reduce superpower tensions. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev emerged as a more moderate leader. Like Eisenhower, who remarked privately that the arms race would lead “at worst to atomic warfare, at best to robbing every people and nation on earth of the fruits of their own toil,” Khrushchev wanted to reduce defense spending and the threat of nuclear devastation. Eisenhower and Khrushchev met in Geneva in 1955 at the first summit conference since the end of World War II. Although the meeting produced no new agreements, it symbolized what Eisenhower called “a new spirit of conciliation and cooperation.”

In August 1957, the Soviets test-fired their first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and, two months later, beat the United States into space by launching Sputnik, the first man-made satellite to circle the earth. The United States launched a successful satellite of its own in January 1958, but Sputnik raised fears that the Soviets led not only in missile development and space exploration but also in science and education. In response, Eisenhower established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with a huge budget increase for space exploration. He also signed the National Defense Education Act, providing support for students in math, foreign languages, and science and technology.

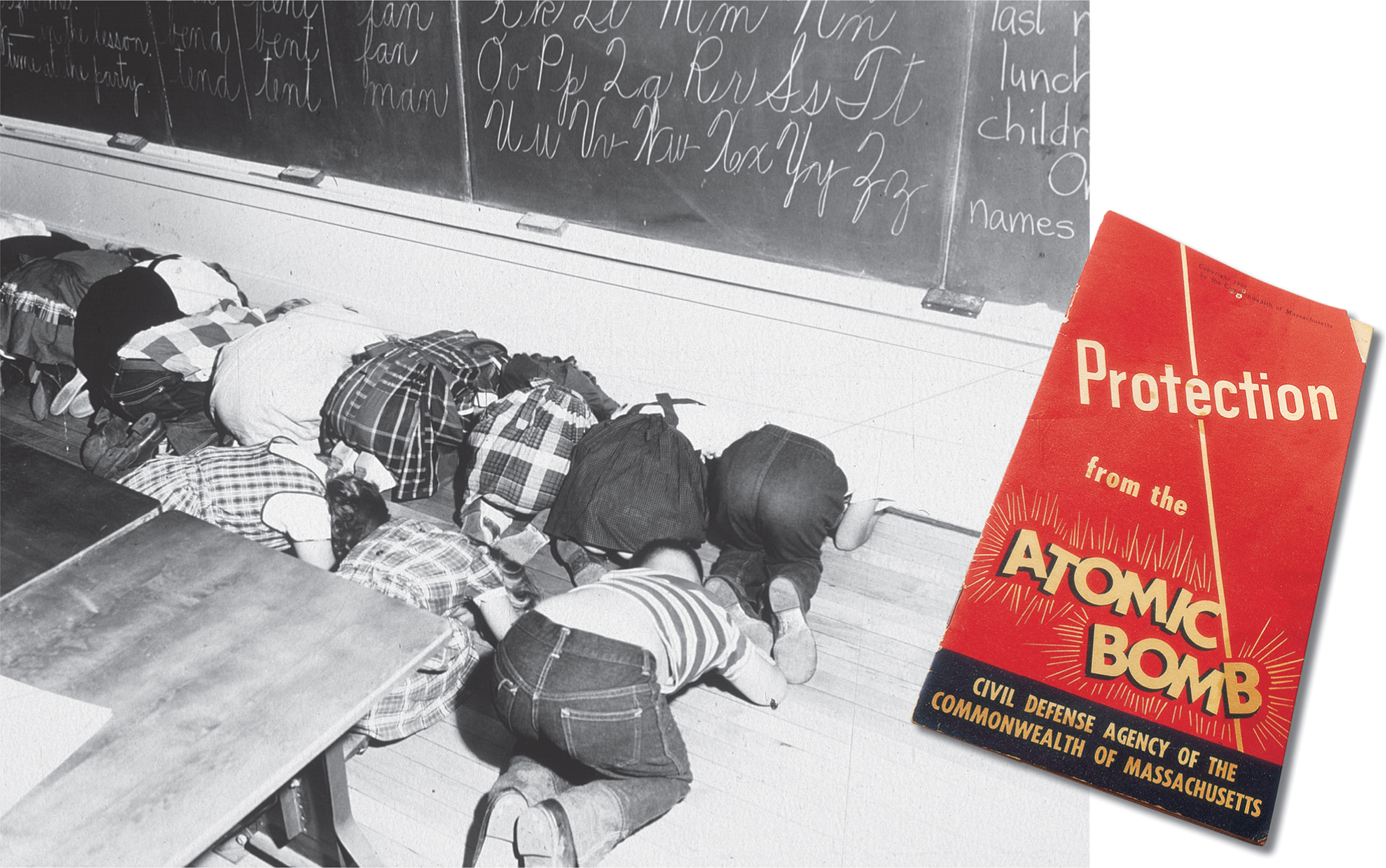

Eisenhower assured the public that the United States possessed nuclear superiority. In fact, during his presidency, the stockpile of nuclear weapons more than quadrupled. With ICBMs at home and in Britain, the United States was prepared to deploy more in Italy and Turkey. In 1960, the United States launched the first Polaris submarine carrying nuclear missiles, yet nuclear weapons could not guarantee security for either superpower because they both possessed sufficient nuclear capacity to devastate each other. Most Americans did not follow Civil Defense Administration recommendations to construct home bomb shelters, but they did realize how precarious nuclear weapons had made their lives.

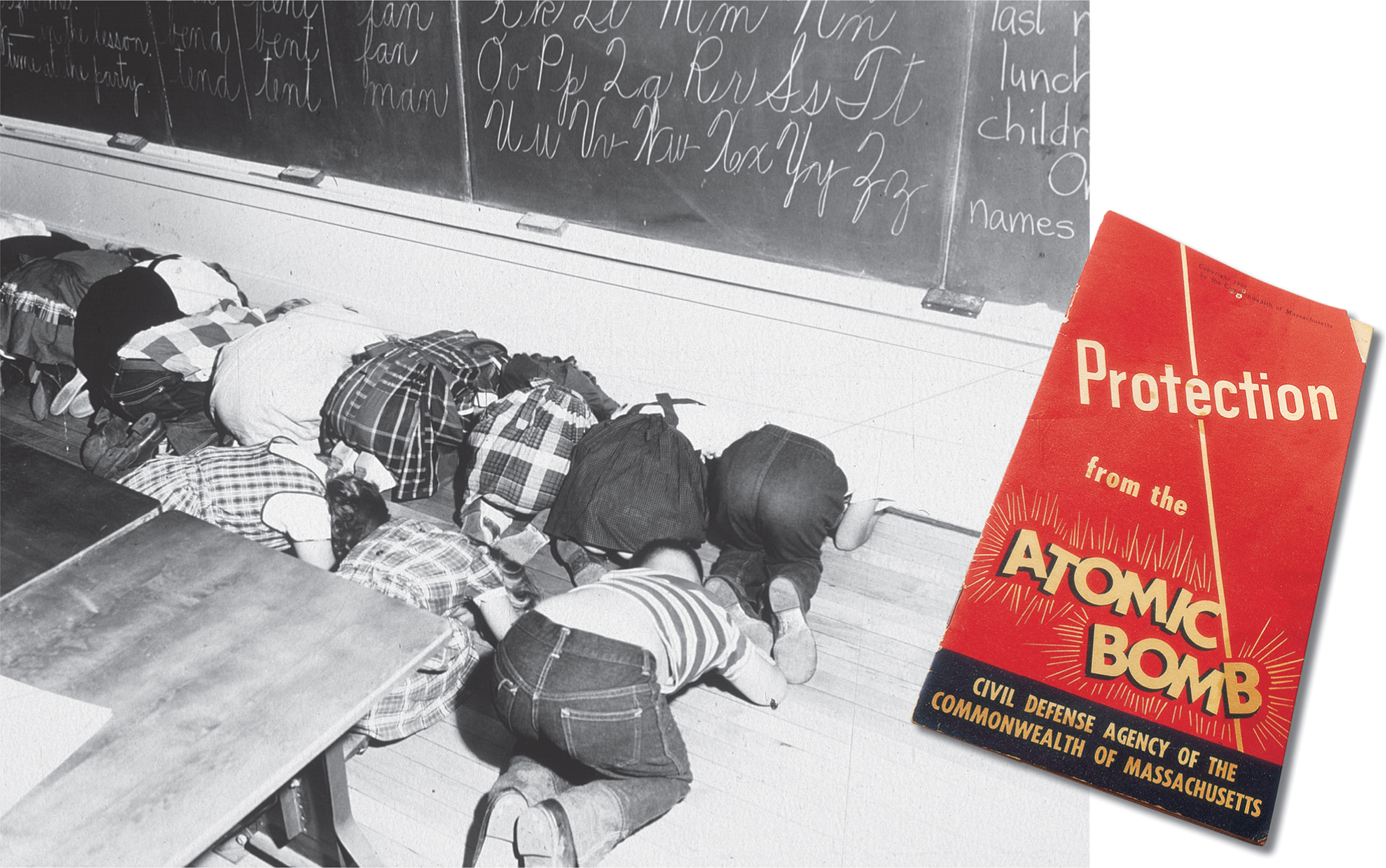

VISUAL ACTIVITY The Age of Nuclear Anxiety As schools routinely held drills to prepare for possible Soviet attacks, children directly experienced the anxiety and insecurity of the 1950s nuclear arms race. The federal government distributed this pamphlet about how to protect oneself from an atomic attack. Photo: Archive Photos/Getty Images; Pamphlet: Lynn Museum and Historical Society. READING THE IMAGE: How effective do you think the strategy pictured here would be in a nuclear attack? Why would the government suggest that civilians could protect themselves? CONNECTIONS: In what other ways did the Cold War shape the everyday lives of Americans?

In the midst of the arms race, the superpowers continued to talk, and by 1960, the two sides were close to a ban on nuclear testing. But just before a planned summit in Paris, a Soviet missile shot down an American U-2 spy plane over Soviet territory. The State Department first denied that U.S. planes had been violating Soviet airspace, but the Soviets produced the pilot and the photos taken on his flight. Eisenhower and Khrushchev met briefly in Paris, but the U-2 incident dashed all prospects for a nuclear arms agreement.

As Eisenhower left office, he warned about the growing influence of the military-industrial complex. Eisenhower had struggled against persistent pressures from defense contractors who, in tandem with the military, sought more dollars for newer, more powerful weapons systems. In his farewell address, he warned that the “conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry . . . exercised a total influence . . . in every city, every state house, every office of the federal government,” but his administration had done little to curtail the defense industry’s power. The Cold War had created a warfare state.

REVIEW Where and how did Eisenhower practice containment?