The American Promise:

Printed Page 838

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 777

Chapter Chronology

Those Who Served

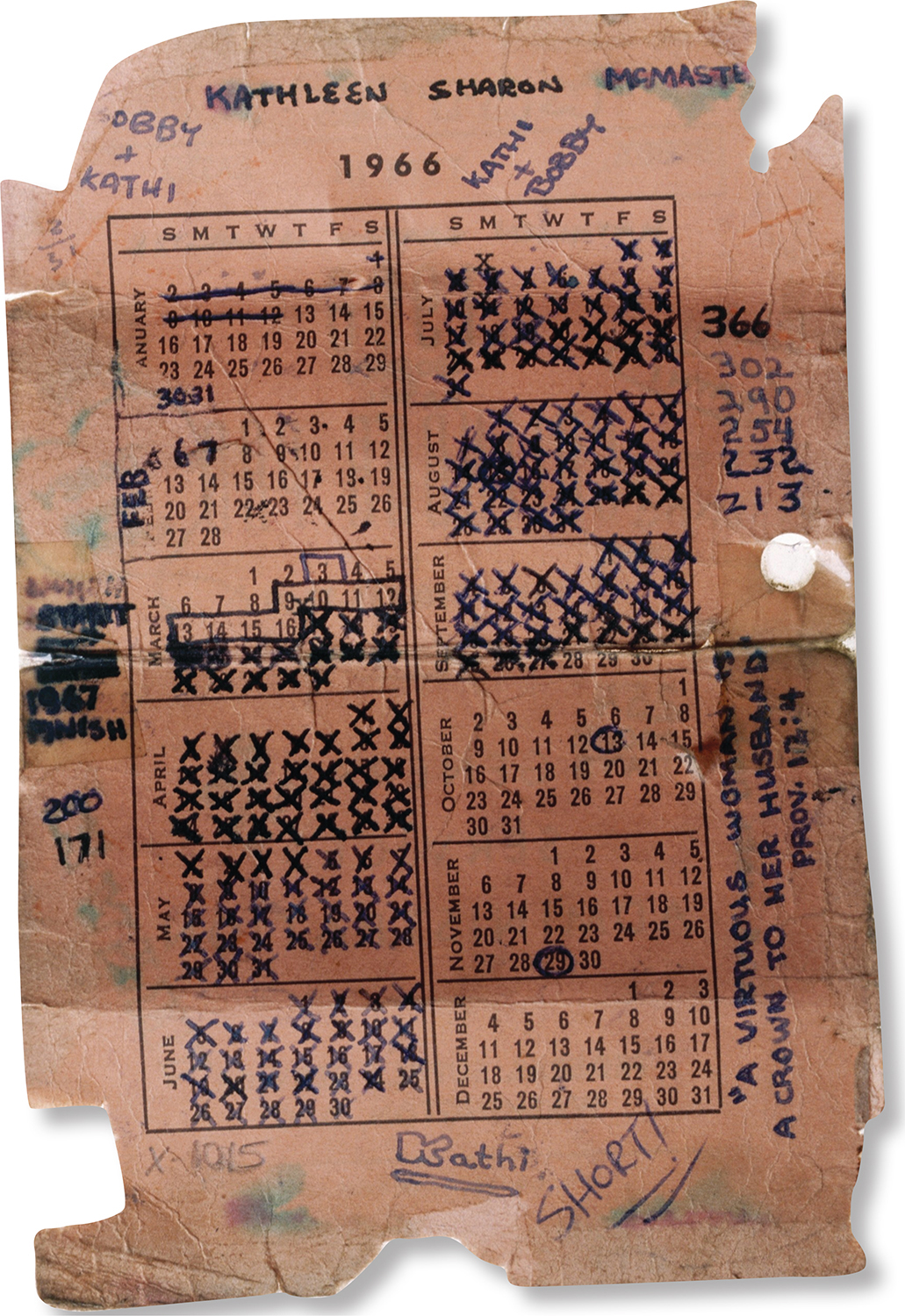

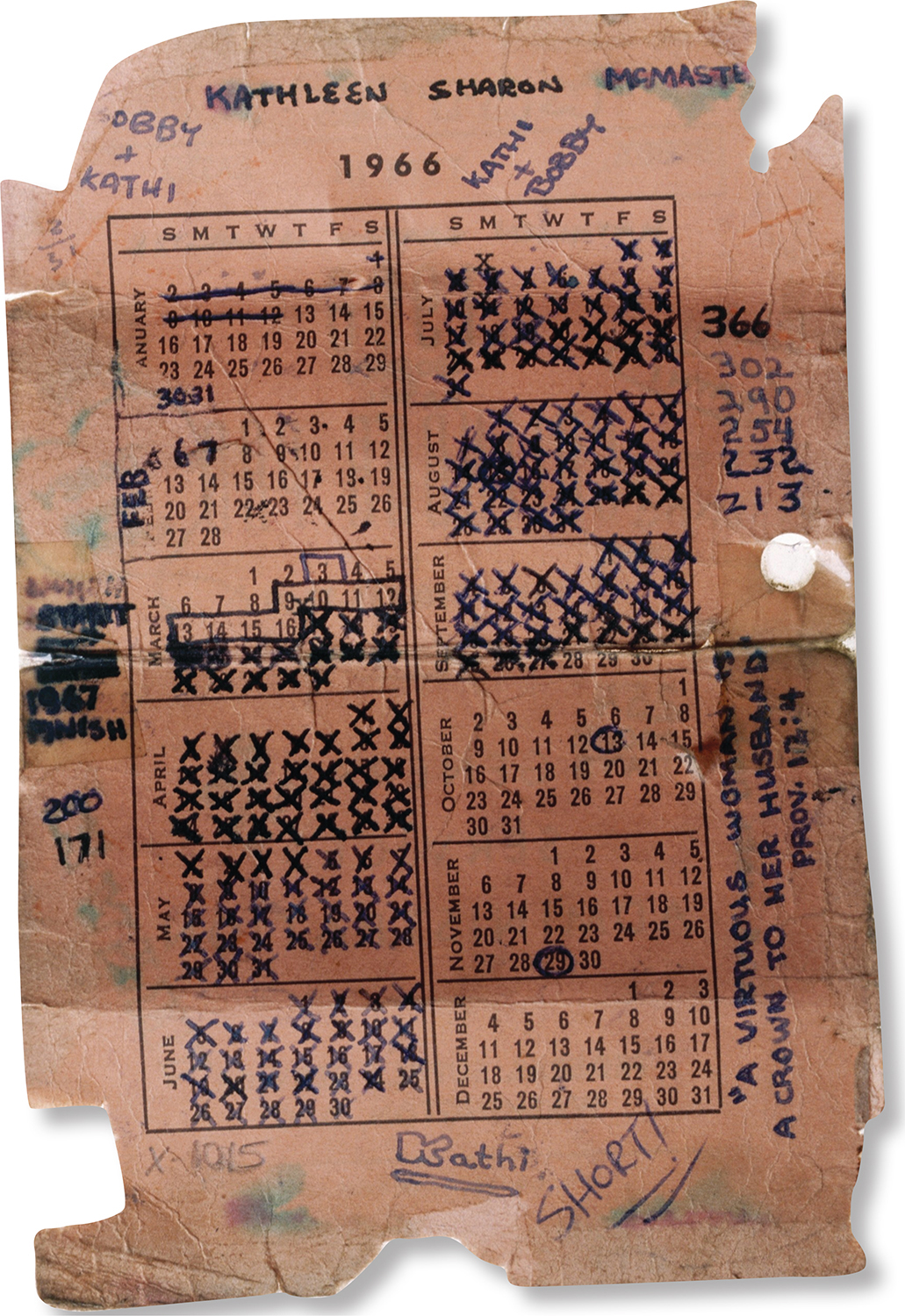

VISUAL ACTIVITY Counting the Days in Vietnam Unlike previous wars, most soldiers served tours of duty in Vietnam lasting just one year. The soldier who carried this calendar expressed a common obsession with time “in country.” Soldiers considered themselves “short” when they had fewer than 100 days left. Bobby McMaster was thinking of either his wife or of the woman he would marry when, and if, he returned home. © Nathan Benn/Corbis. READING THE IMAGE: What does the condition of this calendar suggest about how McMaster spent his time in Vietnam? What concerns about the woman he left behind are expressed in the inscription of the Bible? CONNECTIONS: Besides the length of tours of duty, what other differences existed in the experiences of the soldiers of World War II and those of the Vietnam War?

Teenagers fought the Vietnam War, in contrast to World War II, in which the average soldier was twenty-six years old. All the men in Frederick Downs’s platoon were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one, and the average age for all soldiers was nineteen. Until the Twenty-sixth Amendment to the Constitution dropped the voting age from twenty-one to eighteen in 1971, most soldiers could not even vote for the officials who sent them to war. Men of all classes had fought in World War II, but in Vietnam the poor and working class constituted about 80 percent of the troops. More privileged youths avoided the draft by using college deferments or family connections to get into the National Guard. Sent from Plainville, Kansas, to Vietnam in 1965, Mike Clodfelter could not recall “a single middle-class son of the town’s businessmen, lawyers, doctors, or ranchers from my high school graduating class who experienced the Armageddon of our generation.”

Much more than World War II, Vietnam was a men’s war. Because the United States did not undergo full mobilization for Vietnam, officials did not seek women’s sacrifices for the war effort. Still, between 7,500 and 11,000 women served in Vietnam, the vast majority of them nurses. Some women were exposed to enemy fire, and eight died. Many more struggled with their helplessness to repair the maimed and dead bodies they attended.

Early in the war, African Americans constituted 31 percent of combat troops, often choosing the military over the meager opportunities in the civilian economy. Special forces ranger Arthur E. Woodley Jr. recalled, “The only way I could possibly make it out of the ghetto was to be the best soldier I possibly could.” Death rates among black soldiers were disproportionately high until 1966, when the military adjusted personnel assignments to achieve a better racial balance.

The young troops faced extremely difficult conditions. Frederick Downs’s platoon fought in thick leech-ridden jungles, in rain and oppressive heat, always vulnerable to sniper bullets and land mines. Soldiers in previous wars had served “for the duration,” but in Vietnam a soldier served a one-year tour of duty. A commander called it “the worst personnel policy in history,” because men had less incentive to fight near the end of their tours, wanting merely to stay alive and whole. American soldiers inflicted great losses on the enemy, yet the war remained a stalemate. Many Vietnamese saw the South Vietnamese government as a tool of Western imperialism, full of graft and corruption. Moreover, in the intensified fighting and with the inability to distinguish friend from foe, ARVN and American troops killed and wounded thousands of South Vietnamese civilians and destroyed their villages. By 1968, nearly 30 percent of the population had become refugees. According to Downs, “all Vietnamese had a common desire—to see us go home.” The failure to stabilize South Vietnam even as the U.S. military presence expanded enormously created grave challenges for the administration at home.

REVIEW: Why did massive amounts of airpower and ground troops fail to bring U.S. victory in Vietnam?