The American Promise:

Printed Page 39

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 38

New Spain in the Sixteenth Century

For all practical purposes, Spain was the dominant European power in the Western Hemisphere during the sixteenth century (Map 2.3). Portugal claimed the giant territory of Brazil under the Tordesillas Treaty but was far more concerned with exploiting its hard-

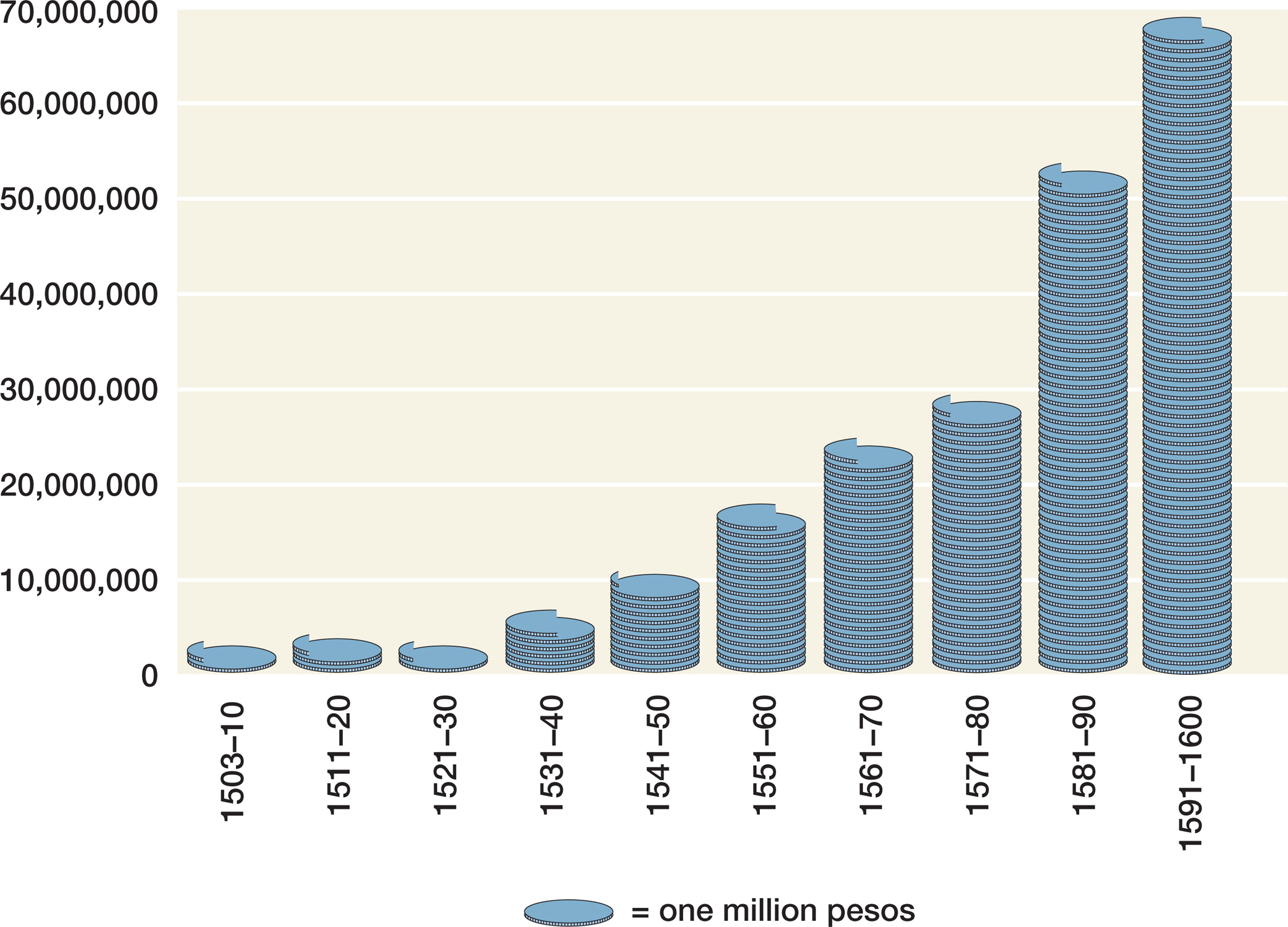

The Spanish monarchy gave the conquistadors permission to explore and plunder what they found. (See “Documenting the American Promise.”) The crown took one-

The distribution of conquered towns institutionalized the system of encomienda, which empowered the conquistadors to rule the Indians empowered the conquistadors to rule the Indians and the lands in and around their towns. Encomienda transferred to the Spanish encomendero (the man who “owned” the town) the tribute that the town had previously paid to the Mexican empire. In theory, the encomendero was supposed to guarantee order and justice, be responsible for the Indians’ material welfare, and encourage them to become Christians.

Catholic missionaries worked hard to convert the Indians. They fervently believed that God expected them to save the Indians’ souls by convincing them to abandon their old sinful beliefs and to embrace the one true Christian faith. (See “Seeking the American Promise.”) But after baptizing tens of thousands of Indians, the missionaries learned that many Indians continued to worship their own gods. Most priests came to believe that the Indians were lesser beings inherently incapable of fully understanding Christianity.

In practice, encomenderos were far more interested in what the Indians could do for them than in what they or the missionaries could do for the Indians. Encomenderos subjected the Indians to chronic overwork, mistreatment, and abuse. According to one Spaniard, “Everything [the Indians] do is slowly done and by compulsion. They are malicious, lying, [and] thievish.” Economically, however, encomienda recognized a fundamental reality of New Spain: The most important treasure the Spaniards could plunder from the New World was not gold but uncompensated Indian labor.

The practice of coerced labor in New Spain grew directly out of the Spaniards’ assumption that they were superior to the Indians. As one missionary put it, the Indians “are more stupid than asses and refuse to improve in anything.” Therefore, most Spaniards assumed, Indians’ labor should be organized by and for their conquerors. Spaniards seldom hesitated to use violence to punish and intimidate recalcitrant Indians.

Encomienda engendered two groups of influential critics. A few missionaries were horrified at the brutal mistreatment of the Indians. “What will [the Indians] think about the God of the Christians,” Friar Bartolomé de Las Casas asked, when they see their friends “with their heads split, their hands amputated, their intestines torn open? . . . Would they want to come to Christ’s sheepfold after their homes had been destroyed, their children imprisoned, their wives raped, their cities devastated, their maidens deflowered, and their provinces laid waste?” Las Casas and other outspoken missionaries softened few hearts among the encomenderos, but they did win some sympathy for the Indians from the Spanish monarchy and royal bureaucracy. The Spanish monarchy moved to abolish encomienda in an effort to replace swashbuckling old conquistadors with royal bureaucrats as the rulers of New Spain.

In 1549, a reform called the repartimiento began to replace encomienda. It limited the labor an encomendero could command from his Indians to forty-

For Spaniards, life in New Spain after the conquests was relatively easy. As one colonist wrote to his brother in Spain, “Don’t hesitate [to come]. . . . This land [New Spain] is as good as ours [in Spain], for God has given us more here than there, and we shall be better off.” During the century after 1492, about 225,000 Spaniards settled in the colonies. Virtually all of them were poor young men of common (non-

The gender and number of Spanish settlers shaped two fundamental features of the society of New Spain. First, Europeans never made up more than 1 or 2 percent of the total population. Although Spaniards ruled New Spain, the population was almost wholly Indian. Second, the shortage of Spanish women meant that Spanish men frequently married Indian women or used them as concubines. The relatively few women from Spain usually married Spanish men, contributing to a tiny elite defined by European origins.

The small number of Spaniards, the masses of Indians, and the frequency of intermarriage created a steep social hierarchy defined by perceptions of national origin and race. Natives of Spain—

The society of New Spain established the precedent for what would become a pronounced pattern in the European colonies of the New World: a society stratified sharply by social origin and race. All Europeans of whatever social origin considered themselves superior to Native Americans; in New Spain, they were a dominant minority in both power and status.