The American Promise:

Printed Page 868

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 803

Chapter Chronology

Energy and Environmental Reform

Complicating the government’s battle with stagflation was the nation’s enormous energy consumption and dependence on foreign nations to fill one-third of its energy demands. Consequently, Carter proposed a comprehensive program to conserve energy, and he elevated its importance by establishing the Department of Energy. Beset with competing demands among energy producers and consumers, Congress picked Carter’s program apart. The National Energy Act of 1978 penalized manufacturers of gas-guzzling automobiles and provided other incentives for conservation and development of alternative fuels, such as wind and solar power, but the act fell far short of a long-term, comprehensive program.

In 1979, a new upheaval in the Middle East, the Iranian revolution, created the most severe energy crisis yet. In midsummer, shortages caused 60 percent of gasoline stations to close down, resulting in long lines and high prices. In response, Congress reduced controls on the oil and gas industry to stimulate American production and imposed a windfall profits tax on producers to redistribute some of the profits they would reap from deregulation.

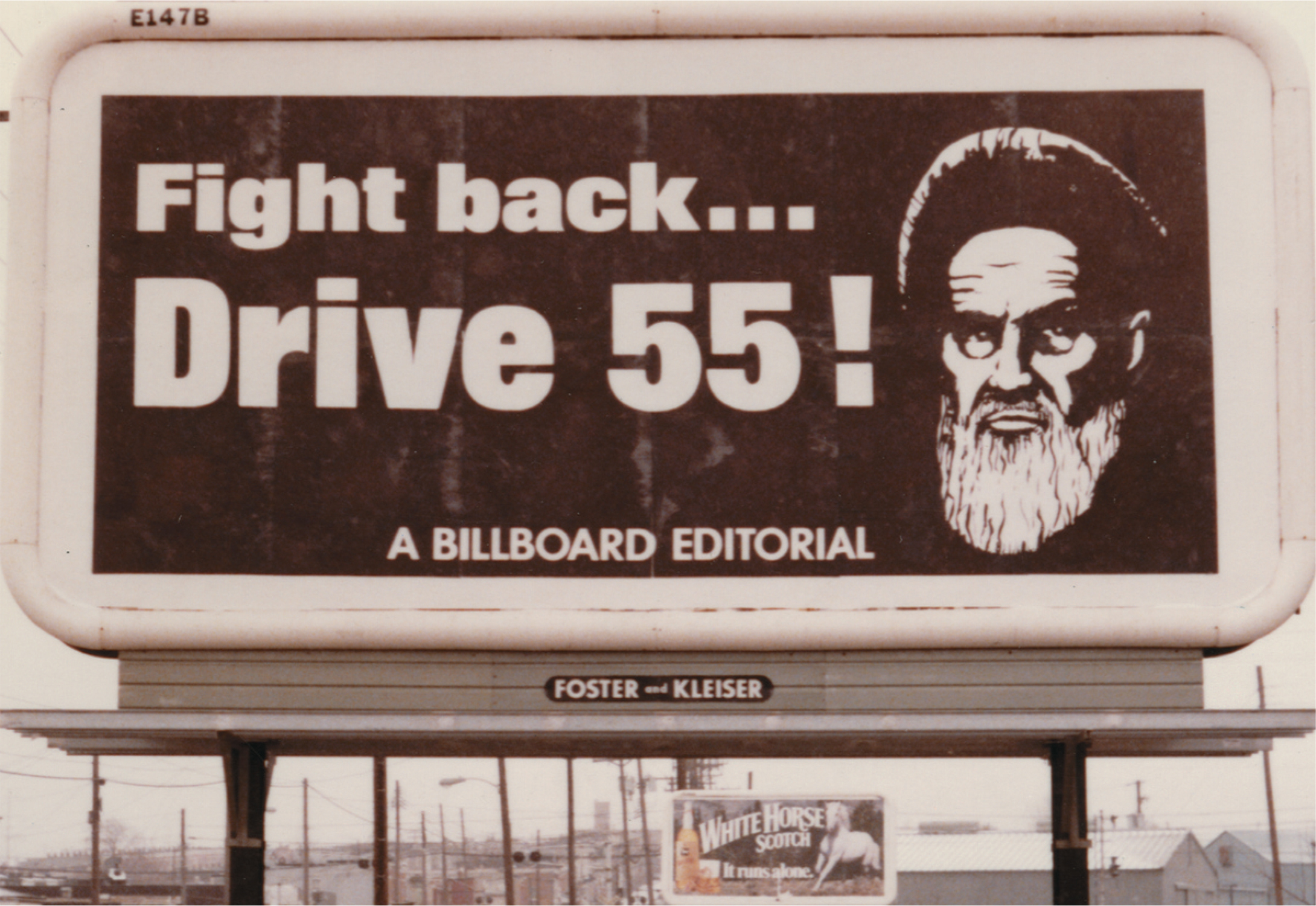

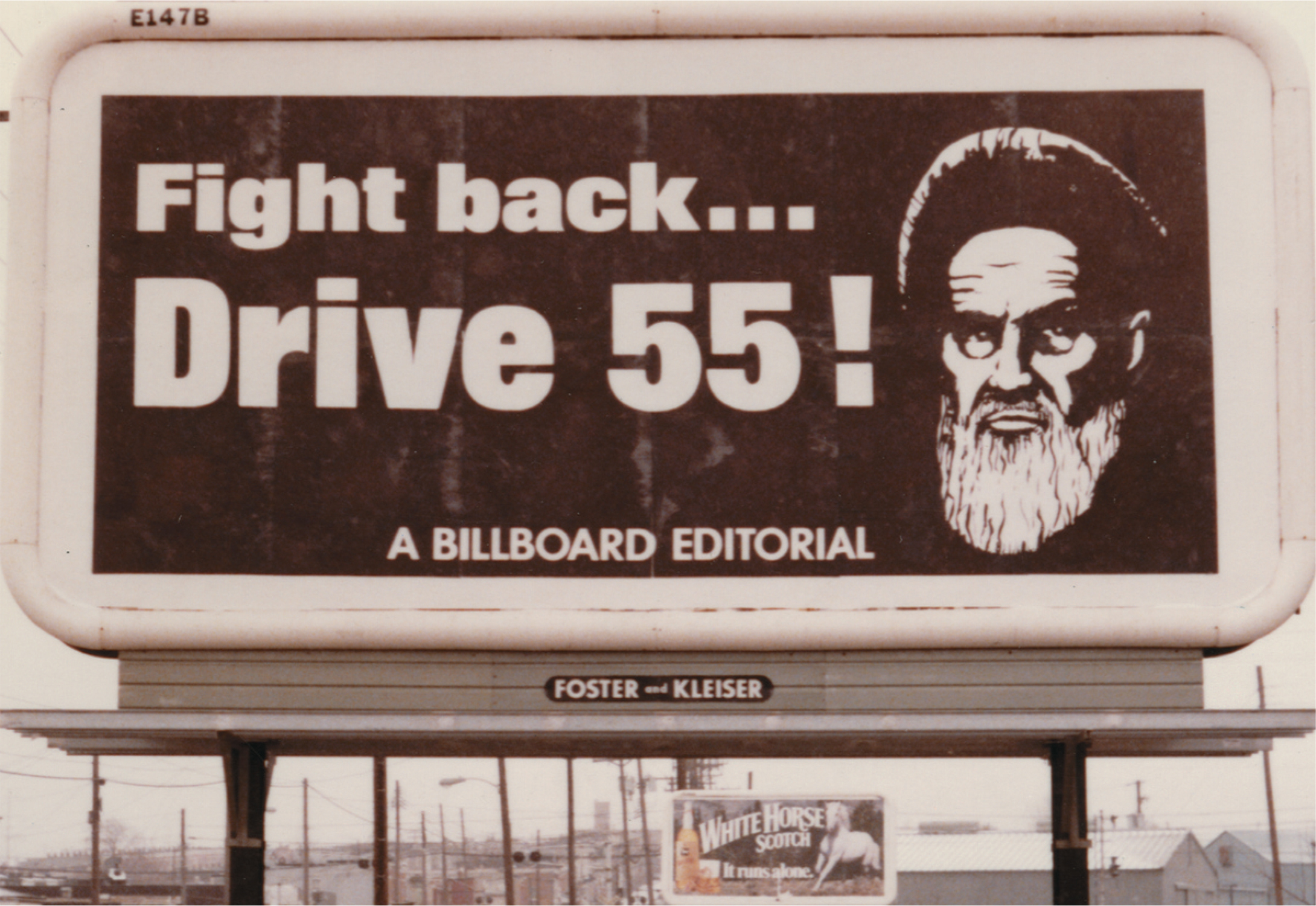

VISUAL ACTIVITY The Fuel Shortage This billboard appeared in 1980 while Iran held Americans hostage in Tehran (see page 872). The Iranian revolution brought to power Ayatollah Ruholla Khomeini, pictured on the billboard, and created gasoline shortages and rising gas prices, vexing motorists all over the United States. The ad urges drivers to observe the fuel-saving 55-mile-per-hour speed limit imposed in 1974 during the first oil crisis. Outdoor Advertising Association of America (OAAA) Archives, David M. Rubenstine Rare Books & Manuscript Library, Duke University READING THE IMAGE: What assumptions does the billboard make about Americans’ reactions to the Iran hostage crisis? What reasons does the ad give for drivers to respect the speed limit? What reasons are not mentioned? CONNECTIONS: What impact did the hostage and oil crises have on American politics?

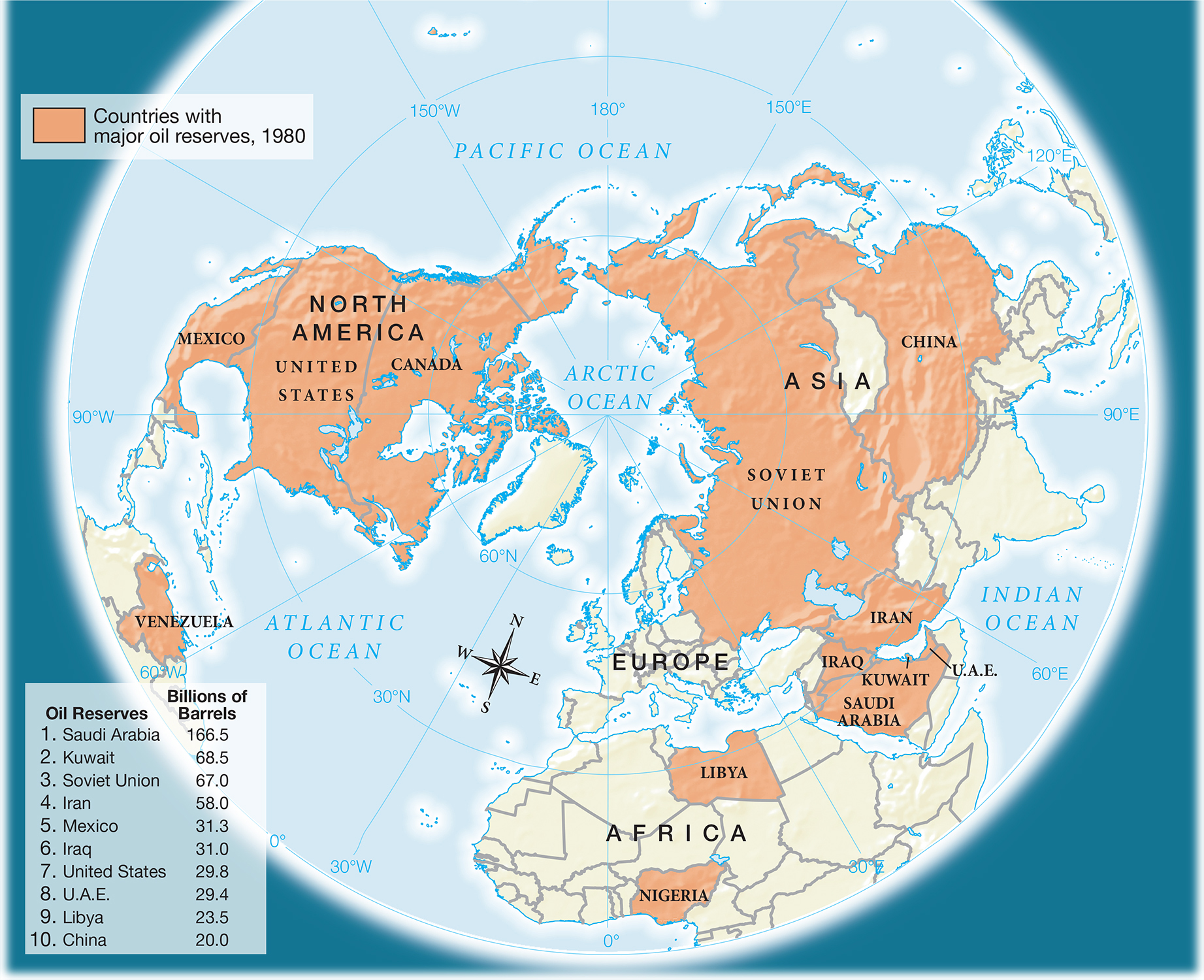

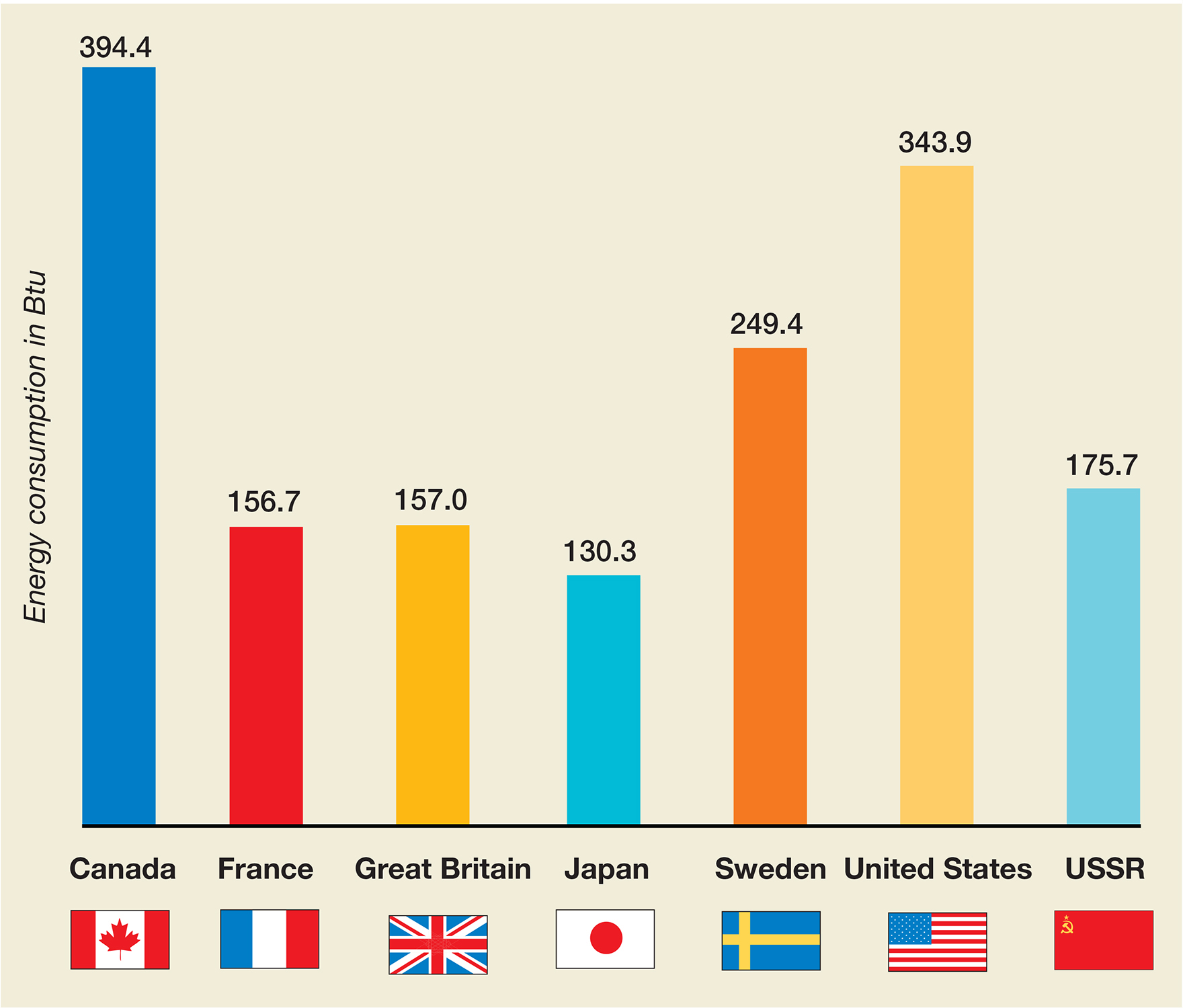

European nations were just as dependent on foreign oil as was the United States, but they more successfully controlled consumption. They levied high taxes on gasoline, causing people to rely more on public transportation and manufacturers to produce more energy-efficient cars. In the automobile-dependent United States, however, with inadequate public transit, a sprawling population, and an aversion to taxes, politicians dismissed that approach. By the end of the century, the United States, with 6 percent of the world’s population, would consume more than 25 percent of global oil production (Figure 30.1 and Map 30.2).

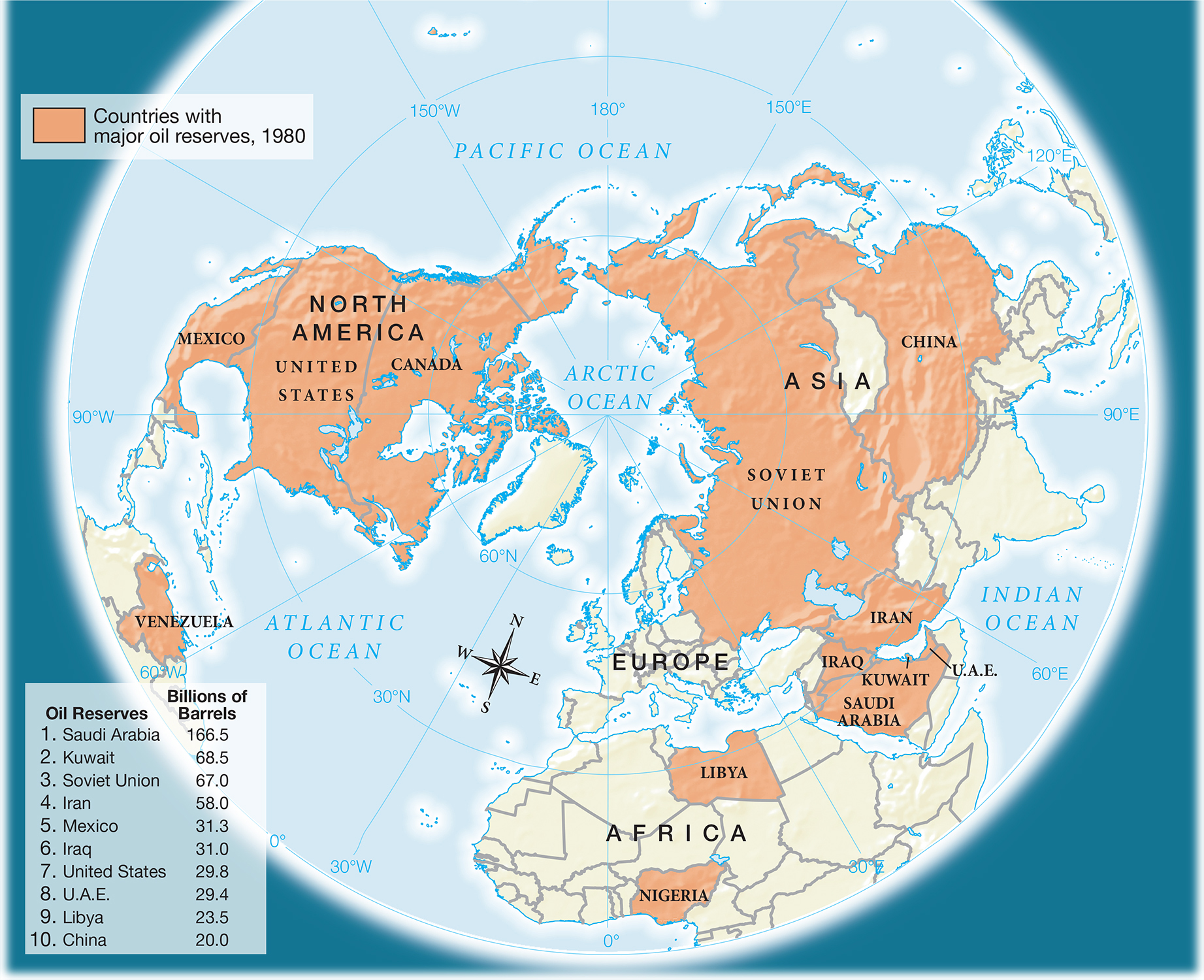

MAP ACTIVITY Map 30.2 Worldwide Oil Reserves, 1980 Geologists and engineers can estimate the size of “proved oil reserves,” quantities recoverable with existing technology and prices. In 1980, worldwide reserves were estimated at 645 billion barrels. Recovery of reserves depends on many factors, including the location of the oil. Large portions of U.S. reserves, for example, lie under the Gulf of Mexico, where it is expensive to drill and where hurricanes can disrupt operations. READING THE MAP: Where did the United States rank in 1980 in the possession of oil reserves? About what portion of the total oil reserves were located in the Middle East? CONNECTIONS: When during the 1970s did the United States experience oil shortages? What caused these shortages?

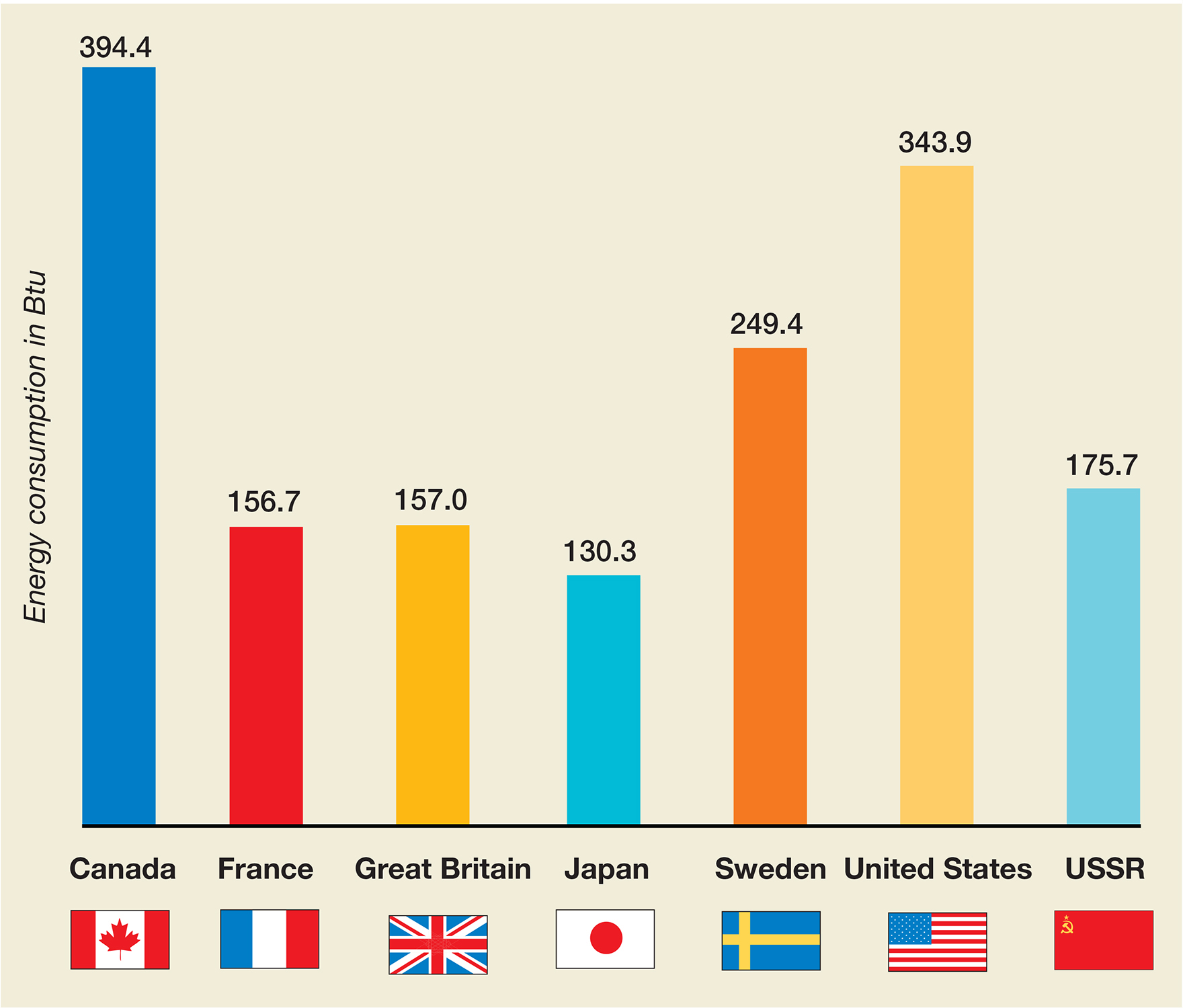

FIGURE 30.1 Global Comparison: Energy Consumption Per Capita, 1980 By 1980, the United States consumed more energy than most other industrialized nations, with a per capita rate of consumption that was more than double that of Britain, France, and Japan and nearly twice as high as that of the Soviet Union. A number of factors influence a nation’s energy consumption, including standard of living, climate, size of landmass, population distribution, availability and price of energy, and government policies.

A vigorous environmental movement opposed nuclear energy as an alternative fuel, warning of radiation leakage, potential accidents, and the hazards of radioactive wastes. In 1976, hundreds of members of the Clamshell Alliance went to jail for attempting to block construction of a nuclear power plant in Seabrook, New Hampshire; other groups sprang up across the country to demand an environment safe from nuclear radiation and waste. The perils of nuclear energy claimed international attention in March 1979, when a meltdown of the reactor core was narrowly averted at the nuclear facility near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Popular opposition and the great expense of building nuclear power plants stalled further development of the industry, which provided 10 percent of the nation’s electricity in the 1970s.

A disaster at Love Canal in Niagara Falls, New York, advanced other environmental goals by underscoring the human costs of unregulated development. Residents suffering high rates of serious illness discovered that their homes sat amid highly toxic waste products from a nearby chemical company. Finally responding to the residents’ claims in 1978, the state of New York agreed to help families relocate, and the Carter administration sponsored legislation in 1980 that created the so-called Superfund, $1.6 billion for cleanup of hazardous wastes left by the chemical industry around the country.

Carter also signed bills to improve clean air and water programs; to expand the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) preserve in Alaska; and to control strip-mining, which left destructive scars on the land. During the 1979 gasoline crisis, Carter attempted to balance the development of domestic fuel sources with environmental concerns, winning legislation to conserve energy and to provide incentives for the development of solar energy and environmentally friendly alternative fuels.