The American Promise:

Printed Page 900

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 833

Chapter Chronology

Defining America’s Place in a New World Order

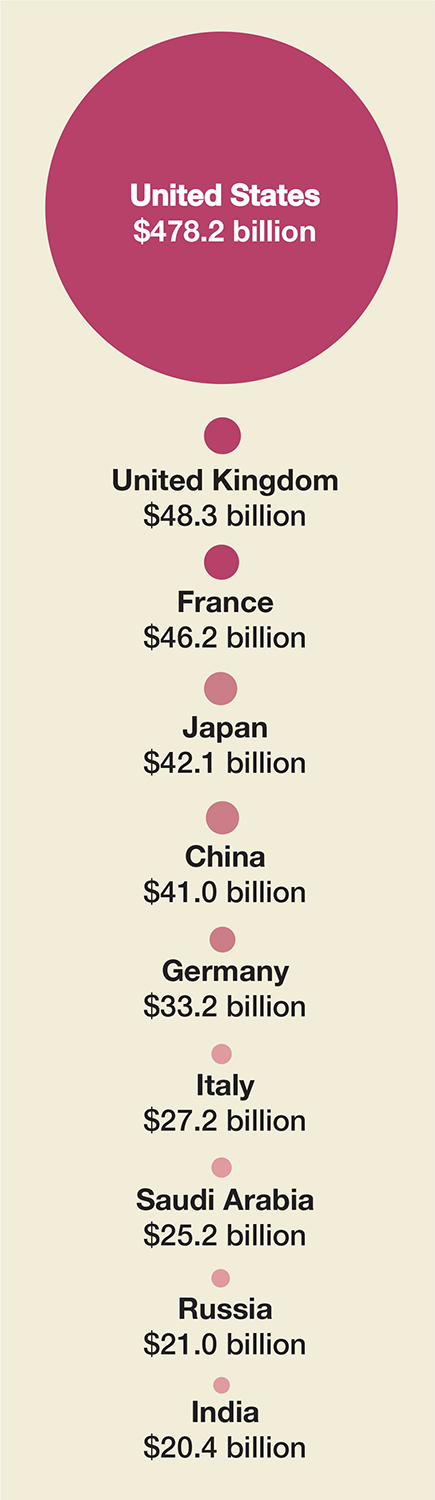

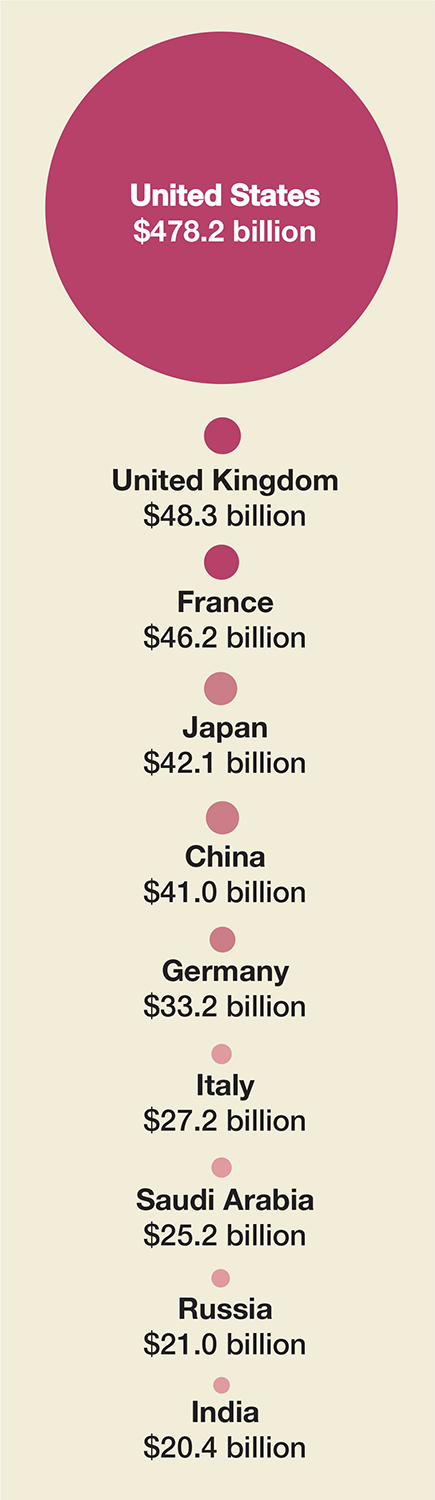

FIGURE 31.2 Global Comparison: Countries with the Highest Military Expenditures, 2005 During the Cold War, the military budgets of the United States and the Soviet Union were relatively even. Even before the Iraq War began in 2003, the U.S. military budget constituted 47 percent of total world military expenditures. Massive defense budgets reflected the determination of Democratic and Republican administrations alike to maintain dominance in the world, even while the capacities of traditional enemies shrunk.

In 1991, President George H. W. Bush declared a “new world order” emerging from the ashes of the Cold War. As the sole superpower, the United States was determined to let no nation challenge its military superiority or global leadership: it spent ten times more on defense than its nearest competitor, China (Figure 31.2). Defining principles for the use of that power in a post–Cold War world remained a challenge.

Africa, where civil wars and extreme human suffering rarely evoked a strong U.S. response, was a case in point. In 1992, President Bush had attached U.S. forces to a UN operation in the northern African country of Somalia, where famine and civil war raged. In 1993, President Clinton allowed that humanitarian mission to turn into “nation building”—an effort to establish a stable government—and eighteen U.S. soldiers were killed. The outcry after Americans saw film of a soldier’s corpse dragged through the streets suggested that most citizens were unwilling to sacrifice lives when no vital interest was threatened. Indeed, both the United States and the UN stood by in 1994 when more than half a million people were massacred in a brutal civil war in Rwanda.

As always, the United States was more inclined to use force nearer its borders. In 1994, after a military coup overthrew Jean-Bertrand Aristide, Haiti’s democratically elected president, Clinton persuaded the United Nations to impose economic sanctions on Haiti and to authorize military intervention. Hours before U.S. forces were to invade, Haitian military leaders promised to step down. U.S. forces peacefully landed, and Aristide was restored to power, but Haiti continued to face grave economic challenges and political instability.

In Eastern Europe, the collapse of communism ignited a severe crisis. During the Cold War, the Communist government of Yugoslavia had held together a federation of six republics. After the Communists were swept out in 1989, ruthless leaders exploited ethnic differences to bolster their power. Yugoslavia splintered into separate states and fell into civil war.

Breakup of Yugoslavia

The Serbian aggression under President Slobodan Milosevic against Bosnian Muslims, which included rape, torture, and mass killings, horrified much of the world, but European and U.S. leaders hesitated to use military force. Finally, in 1995, Clinton ordered U.S. fliers to join NATO forces in intensive bombing of Serbian military concentrations. That effort and successful offensives by the Croatian and Bosnian armies forced Milosevic to the bargaining table, where representatives from Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia hammered out a peace treaty.

In 1998, new fighting broke out in the southern Serbian province of Kosovo, where ethnic Albanians, who constituted 90 percent of the population, demanded independence. When the Serbian army retaliated, in 1999, NATO launched a U.S.-led bombing attack on Serbian military and government targets that, after three months, forced Milosevic to agree to a settlement. Serbians voted Milosevic out of office in October 2000, and he died in 2006 while on trial for genocide by a UN war crimes tribunal.

VISUAL ACTIVITY Ethnic Strife in Kosovo In 1999, American troops joined a NATO peacekeeping force in the former Yugoslav province of Kosovo. Here, an ethnic Albanian boy walks beside Specialist Brent Baldwin as the soldier patrols the town of Gnjilane in southeast Kosovo in May 2000. AP Photo. READING THE IMAGE: What attitude about the U.S. soldiers does this boy display? What did the presence of American troops mean to people like him? CONNECTIONS: Where else did President Clinton deploy military force in the 1990s?

Events in Israel since 1989

Elsewhere, Clinton deployed U.S. power when he could send missiles rather than soldiers, and he was prepared to act without international support or UN sanction. In August 1998, bombings at the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania killed 12 Americans and more than 250 Africans. Clinton retaliated with missile attacks on terrorist training camps in Afghanistan and facilities in Sudan controlled by Osama bin Laden, a Saudi-born millionaire who financed Al Qaeda, the Islamic-extremist terrorist network linked to the embassy attacks. Clinton also launched air strikes against Iraq in 1993 when a plot to assassinate former president Bush was uncovered, in 1996 after Saddam Hussein attacked the Kurds in northern Iraq, and repeatedly between 1998 and 2000 after Hussein expelled UN weapons inspectors. Whereas Bush had acted in the Gulf War with the support of an international force that included Arab states, Clinton acted unilaterally and in the face of Arab opposition.

To defuse the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Clinton applied diplomatic rather than military power. In 1993, Norwegian diplomats had brokered an agreement between Yasir Arafat, head of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and Yitzhak Rabin, Israeli prime minister, to recognize the existence of each other’s states. Israel agreed to withdraw from the Gaza Strip and Jericho, allowing for Palestinian self-government there. In July 1994, Clinton presided over another turning point as Rabin and King Hussein of Jordan signed a declaration of peace. Yet difficult issues remained, especially control of Jerusalem and the presence of more than 200,000 Israeli settlers in the West Bank, the land seized by Israel in 1967, where three million Palestinians were determined to establish their own state.