The American Promise:

Printed Page 100

BEYOND AMERICA’S BORDERS

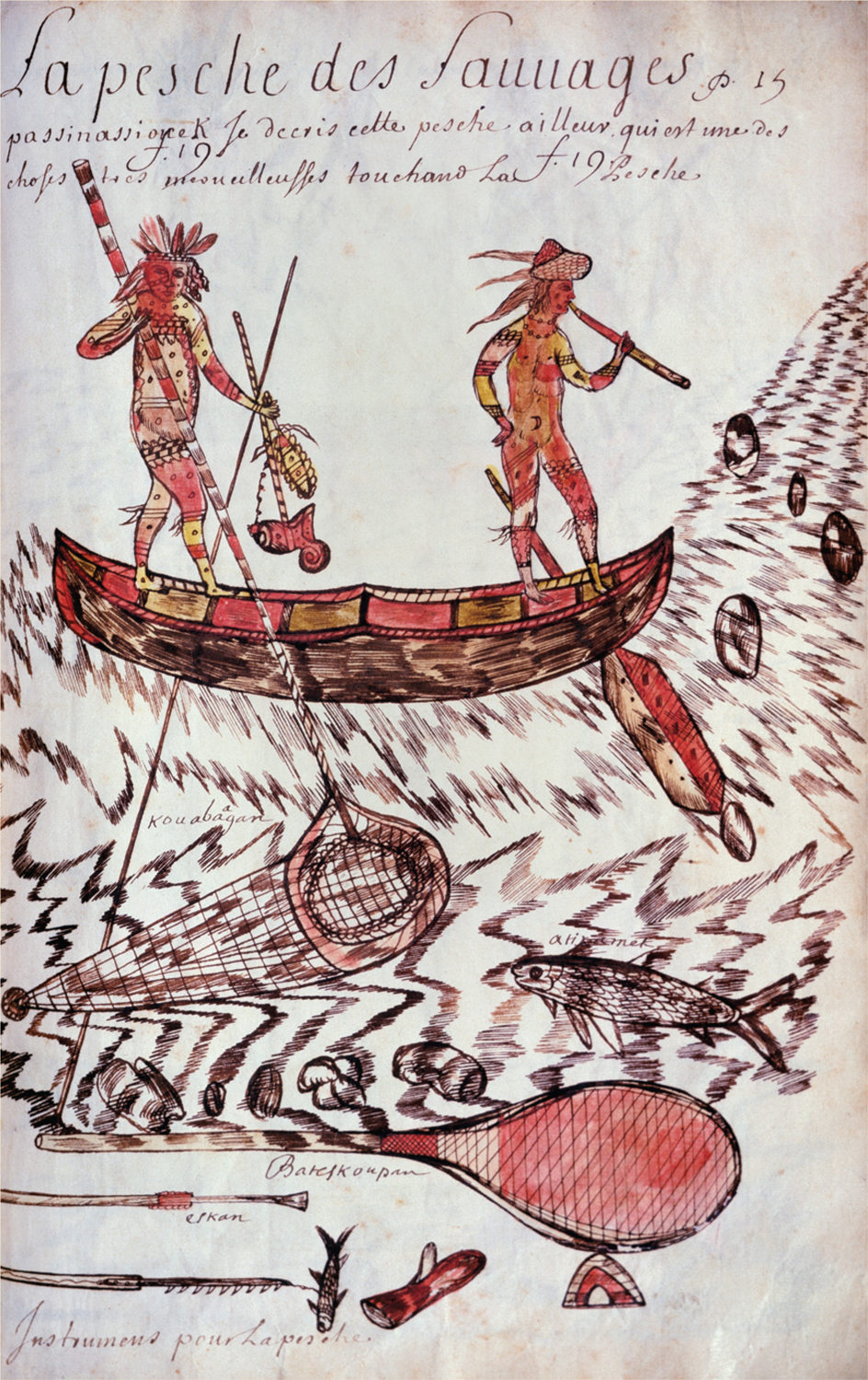

New France and the Indians: The English Colonies’ Northern Borderlands

North of New England, French explorers, traders, and missionaries carved out a distinctive North American colony that contrasted, competed, and periodically fought with the English colonies to the south.

The explorer Jacques Cartier sailed into the St. Lawrence River in 1535 and claimed the region for France. Cartier’s attempts to found a permanent colony failed, but French ships followed in his wake and began to trade with Native Americans for wild animal pelts. By the time King Louis XIV made New France a royal colony in 1663, the fur trade had become the colony’s economic foundation.

The French monarchy hoped to channel the fur trade through French hands into the broader European market and to compete against rival Dutch traders, whose headquarters at Albany (in what is now New York) funneled North American furs down the Hudson River to markets in the Netherlands. The crown also hoped the fur trade would allow the creation of a North American colony on the cheap.

The fur trade required little investment other than the construction and staffing of trading outposts at Quebec, Montreal, and elsewhere. In exchange for textiles and various metal trade goods, the Iroquois, Huron, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and other Native Americans did the arduous, time-

After England seized control of New York in 1664, English fur traders replaced the Dutch at Albany and eagerly competed to divert the northern fur trade away from New France. By then, the Iroquois—

Native Americans preferred English trade goods, which tended to be of higher quality and less expensive than those available at French outposts, but New France cultivated better relationships with the Indians. When English colonists had the required military strength, they seldom hesitated to kill Indians, especially those who occupied land the colonists craved. The small number of colonists in New France never had as much military power as the English colonists; hence, they sought to stay on relatively peaceful and friendly terms with the Indians. French men commonly married or cohabited with Indian women, an outgrowth of both the shortage of French women among the colonists and the acceptance of such couplings, compared with the strong taboo prevalent in the English colonies.

Jesuit missionaries led the spiritual colonization of New France. Zealous enemies of what they considered Protestant heresies and stout defenders of Catholicism, the Jesuits fanned out to Indian villages throughout New France, determined to convert the Native Americans and to preserve the colony as a Catholic stronghold. Unwittingly, the missionaries also spread European diseases among the Native Americans, repeatedly causing deadly epidemics. Above all, the missionaries worked hand in hand with the fur traders and royal officials to make New France a low-

To extend the boundaries of New France far to the west and south, almost encircling the English colonies along the Atlantic coast, royal officials in 1673 sponsored a voyage by the explorer Louis Jolliet and the priest Jacques Marquette to explore the vast interior of the North American continent by canoeing down the Mississippi River to what is now Arkansas. Jolliet and Marquette made grandiose claims to the Mississippi valley, but in reality these claims amounted to little more than a colored patch on European maps. The dominant military power in New France remained the Iroquois, not the French.

England and France clashed repeatedly in North America over the fur trade and in a colonial extension of their rivalry at home. European conflict between France and England spread to North America during King William’s War (1689–

America in a Global Context

- In what ways did New France reflect the colonial objectives of the French monarchy?

- How did New France differ from the English colonies in seventeenth-

century North America? - How did European rivalries influence the encounters of Indians with French and English colonists?

Connect to the Big Idea

Why was New France important to the seventeenth-