The American Promise:

Printed Page 84

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 81

Church, Covenant, and Conformity

Puritans believed that a church consisted of men and women who had entered a solemn covenant with one another and with God. Winthrop and others who signed the covenant of the first Boston church in 1630 agreed to “Promisse, and bind our selves, to walke in all our wayes according to the Rule of the Gospell, and in all sincere Conformity to His holy Ordinaunces.” Each new member of the covenant had to persuade existing members that she or he had fully experienced conversion.

Puritans embraced a distinctive version of Protestantism derived from Calvinism, the doctrines of John Calvin, who insisted that Christians strictly discipline their behavior to conform to God’s commandments announced in the Bible. Like Calvin, Puritans believed in predestination—the idea that the all-

Despite the looming uncertainty about God’s choice of the elect, Puritans believed that if a person lived a rigorously godly life—

The connection between sainthood and saintly behavior, however, was far from certain. Some members of the elect, Puritans believed, had not heard God’s Word. One reason Puritans required all town residents to attend church services was to enlighten anyone who was ignorant of God’s Truth. The slippery relationship between saintly behavior and God’s predestined election caused Puritans to worry constantly that individuals who acted like saints were fooling themselves and others. Nevertheless, Puritans thought that visible saints—persons who passed their demanding tests of conversion and church membership—

Members of Puritan churches ardently hoped that God had chosen them to receive eternal life and tried to demonstrate saintly behavior. Their covenant bound them to help one another attain salvation and to discipline the entire community by saintly standards. Church members kept an eye on the behavior of everybody in town. By overseeing every aspect of life, the visible saints enforced a remarkable degree of righteous conformity in Puritan communities. Total conformity, however, was never achieved. Ardent Puritans differed among themselves, and non-

Despite the central importance of religion, churches played no direct role in the civil government of New England communities. Puritans did not want to mimic the Church of England, which they considered a puppet of the king rather than an independent body that served the Lord. They were determined to insulate New England churches from the contaminating influence of the civil state and its merely human laws. Ministers were prohibited from holding government office.

Puritans had no qualms, however, about their religious beliefs influencing New England governments. As much as possible, the Puritans tried to bring public life into conformity with their view of God’s law. For example, fines were issued for Sabbath-

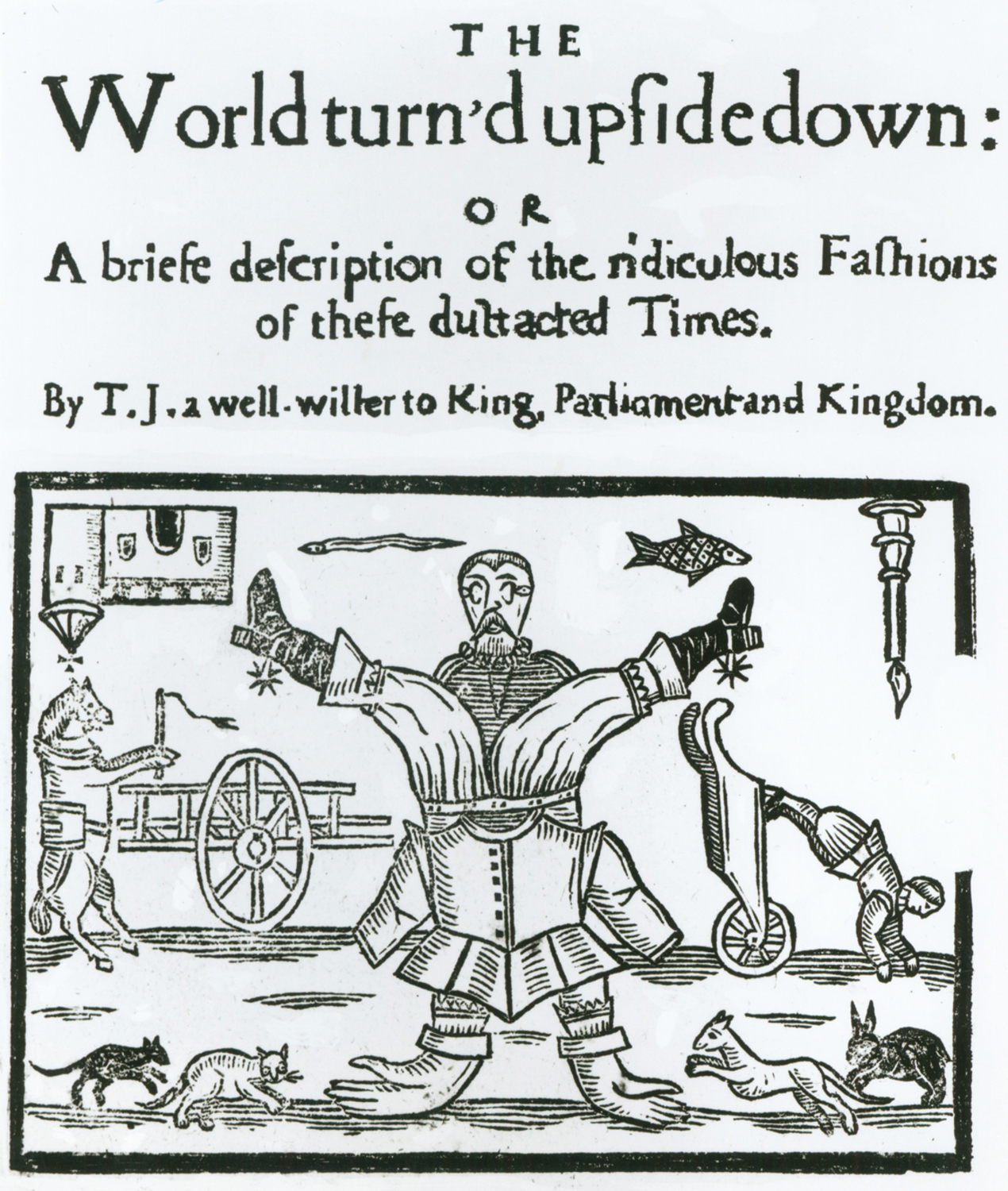

Puritans mandated other purifications of what they considered corrupt English practices. (See “Visualizing History.”) They refused to celebrate Christmas or Easter because the Bible did not mention either one. They outlawed religious wedding ceremonies; couples were married by a magistrate in a civil ceremony. They banned cards, dice, shuffleboard, and other games of chance, as well as music and dancing. “Mixt or Promiscuous Dancing . . . of Men and Women” could not be tolerated since “the unchaste Touches and Gesticulations used by Dancers have a palpable tendency to that which is evil.”