The American Promise:

Printed Page 112

SEEKING THE AMERICAN PROMISE

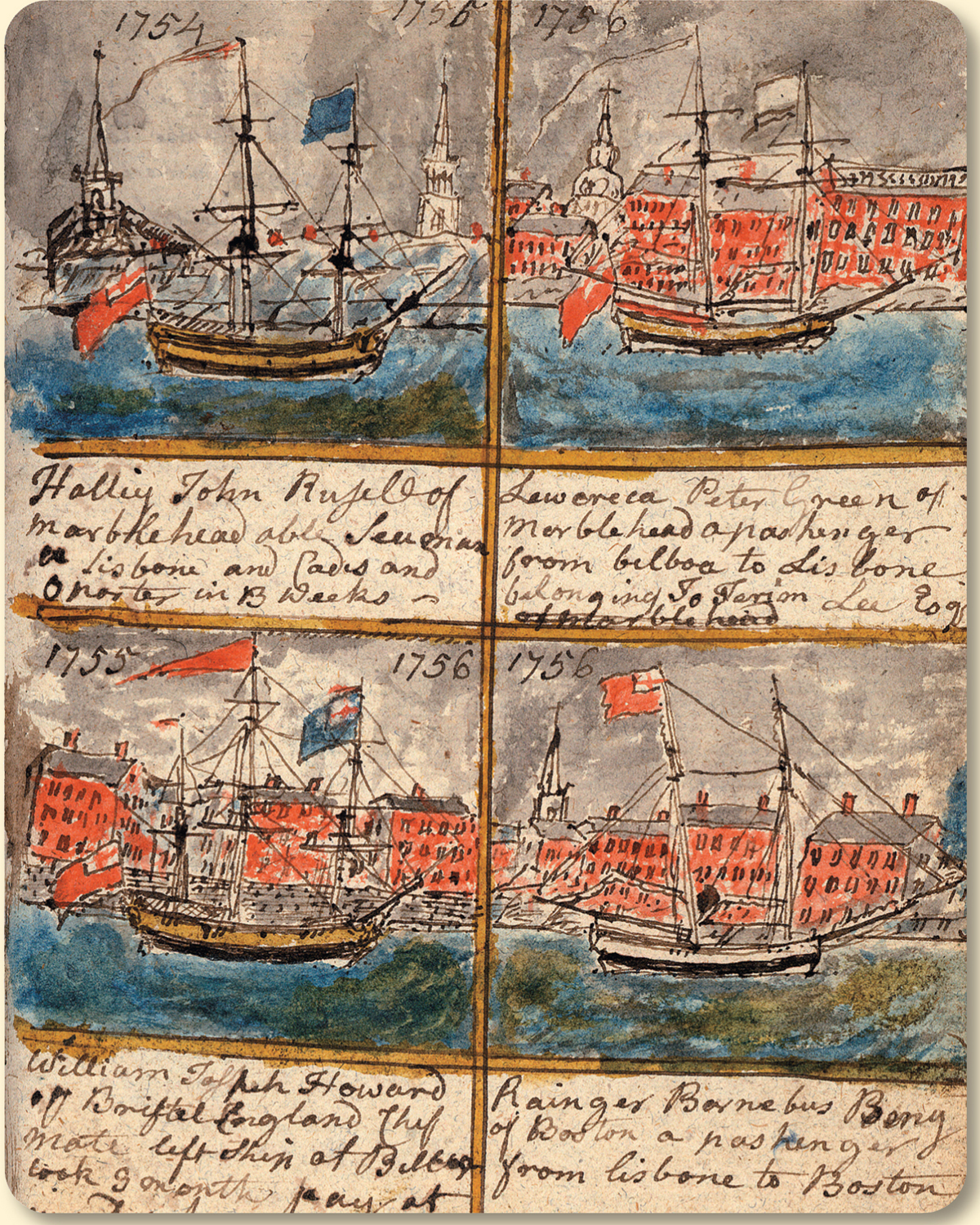

A Sailor’s Life in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World

Although most eighteenth-

Despite the certainty of strenuous work and spartan accommodations, young men like Ashley Bowen made their way to wharves in small ports such as Marblehead, Massachusetts—

Born in 1728, Bowen grew up in Marblehead, one of the most important fishing ports in North America. Like other boys who lived in or near ports, Bowen probably watched ships come and go; heard tales of adventure, disaster, and intrigue; and learned from neighbors and pals how to maneuver small, shallow-

Most commonly, young men first went to sea when they were fifteen to eighteen years old. Like Bowen, they were single, living with their parents, and casting about for work. They usually sailed with friends, neighbors, or kinfolk, and they sought an education in the ways of the sea. Also like Bowen, they aspired to earn some wages, to rise in the ranks eventually from seaman to mate and possibly to master (the common term for captain), to save enough to marry and support a family, and after twenty years or so to retire from the rigors of the seafaring life with a “competency”—that is, enough money to live modestly.

It typically took about four years at sea to become a fully competent seaman. Shortly after Bowen returned from his first voyage, his father apprenticed him to a sea captain for seven years. In return for a hefty payment, the captain agreed to tutor young Bowen in the art of seafaring, which ideally promised to ease his path to become a captain himself. In reality, the captain employed him as a cabin boy, taught him little except to obey, and beat him for trivial mistakes, causing Bowen to run away after four years of servitude.

Now seventeen years old, Bowen had already sailed to dozens of ports in North America, the West Indies, the British Isles, and Europe. For the next eighteen years, he shipped out as a common seaman on scores of vessels carrying nearly every kind of cargo afloat on the Atlantic. He sailed mostly aboard merchant freighters, but he also worked on whalers, fishing boats, privateers, and warships. He survived sickness, imprisonment, foul weather, accidents, and innumerable close calls. But when he retired from seafaring at age thirty-

Like Bowen, about three out of ten seamen spent their entire seafaring lives as seamen or mates, earning five dollars or so a month in wages, roughly comparable to the wages of farm laborers. Another three out of ten seamen died at sea, many by drowning or as a result of injuries or, most commonly, from tropical diseases usually picked up in the West Indies. Bowen lived to the age of eighty-

Questions for Consideration

- What attracted Ashley Bowen to a seafaring life? How successful was he?

- How did Bowen’s experiences as a seaman compare to those of farmers in the colonies?

- How might Bowen’s outlook on the world compare to that of the vast majority of colonists who seldom or never went to sea?

Connect to the Big Idea

How did the lives of farmers and merchants in eighteenth-