The American Promise:

Printed Page 137

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 130

French-British Rivalry in the Ohio Country

For several decades, French traders had cultivated alliances with the Indian tribes in the Ohio Country, a frontier region they regarded as part of New France, establishing a profitable exchange of manufactured goods for beaver furs (Map 6.1). But in the 1740s, aggressive Pennsylvania traders began to infringe on the territory. Adding to the tensions, a group of enterprising Virginians, including the brothers Lawrence and Augustine Washington, formed the Ohio Company in 1747 and advanced on the same land. Their hope for profit lay not in the fur trade but in land speculation, fueled by American population expansion.

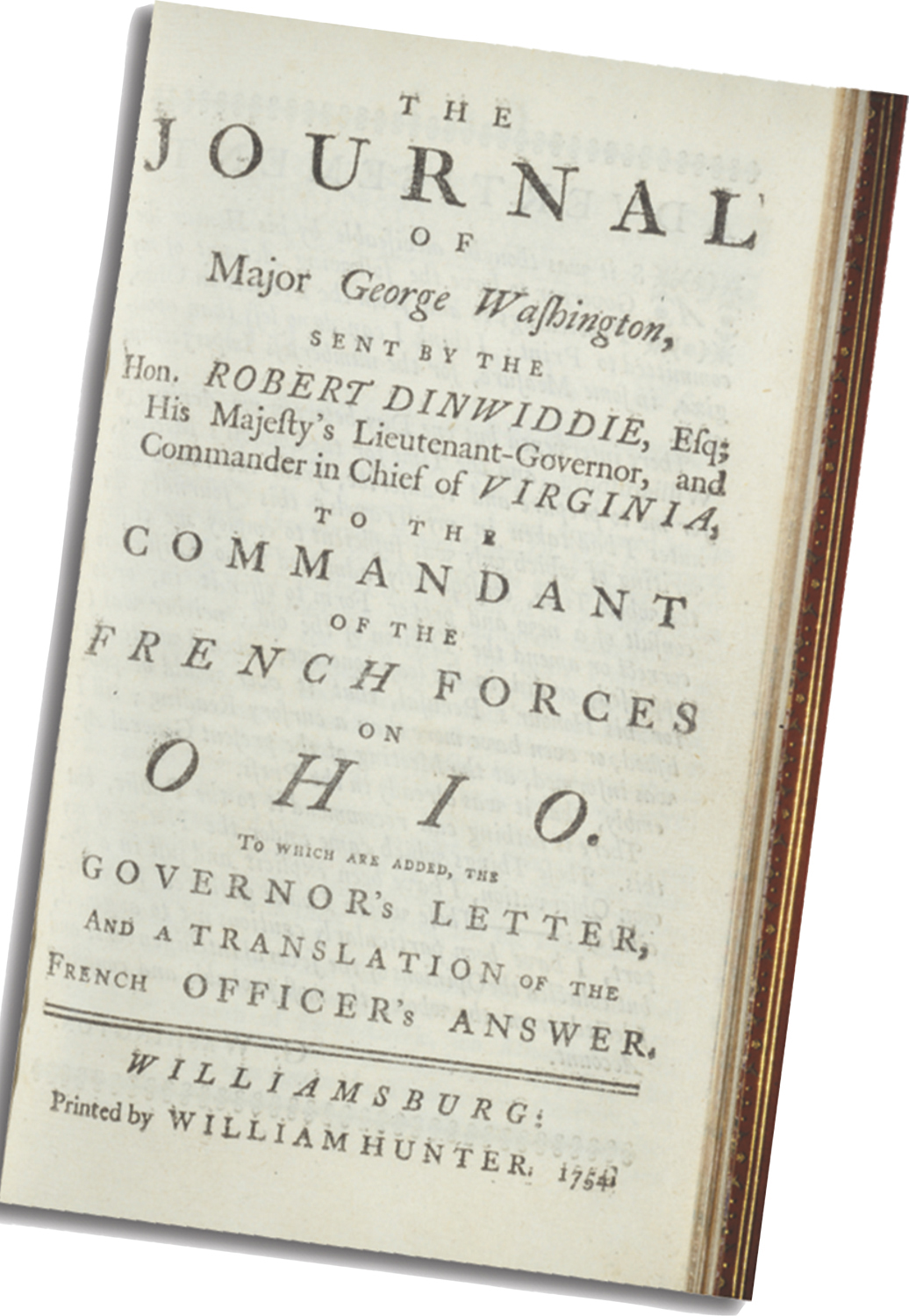

In response to these incursions, the French sent soldiers to build a series of military forts to secure their trade routes and to create a western barrier to American expansion. In 1753, the royal governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie, himself a shareholder in the Ohio Company, dispatched a messenger to warn the French that they were trespassing on Virginia land. For this dangerous mission, he chose the twenty-

In the spring of 1754, Washington set out with 160 Virginians and a small contingent of Mingo Indians equally concerned about the French military presence in the Ohio Country. Early one morning the Mingo chief Tanaghrisson led a detachment of Washington’s soldiers to a small French encampment in the woods. Who fired first was in dispute, but fourteen Frenchmen (and no Virginians) were wounded. While Washington, lacking a translator, struggled to communicate with the injured French commander, Tanaghrisson and his men intervened to kill and then scalp the wounded soldiers, including the commander, probably with the aim of inflaming hostilities between the French and the colonists.

This sudden massacre violated Dinwiddie’s instructions to Washington and raised the stakes considerably. Fearing retaliation, Washington ordered his men to throw together a makeshift “Fort Necessity.” Several hundred Virginia reinforcements arrived, but the Mingos, sensing disaster and displeased by Washington’s style of command, fled. (Tanaghrisson later said, “The Colonel was a good-