The American Promise:

Printed Page 174

VISUALIZING HISTORY

Keeping Powder Dry

Musket-

During the considerable down-

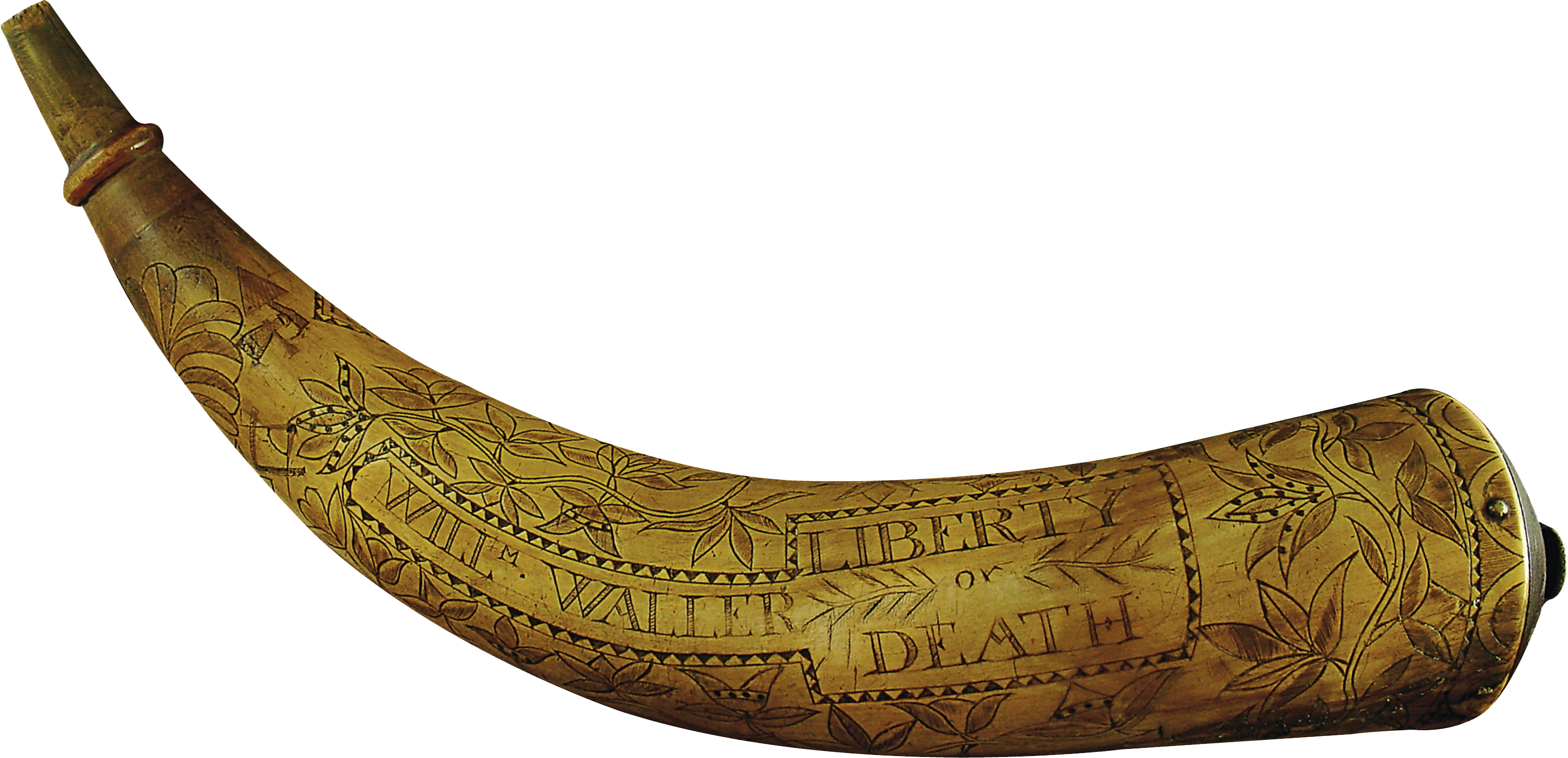

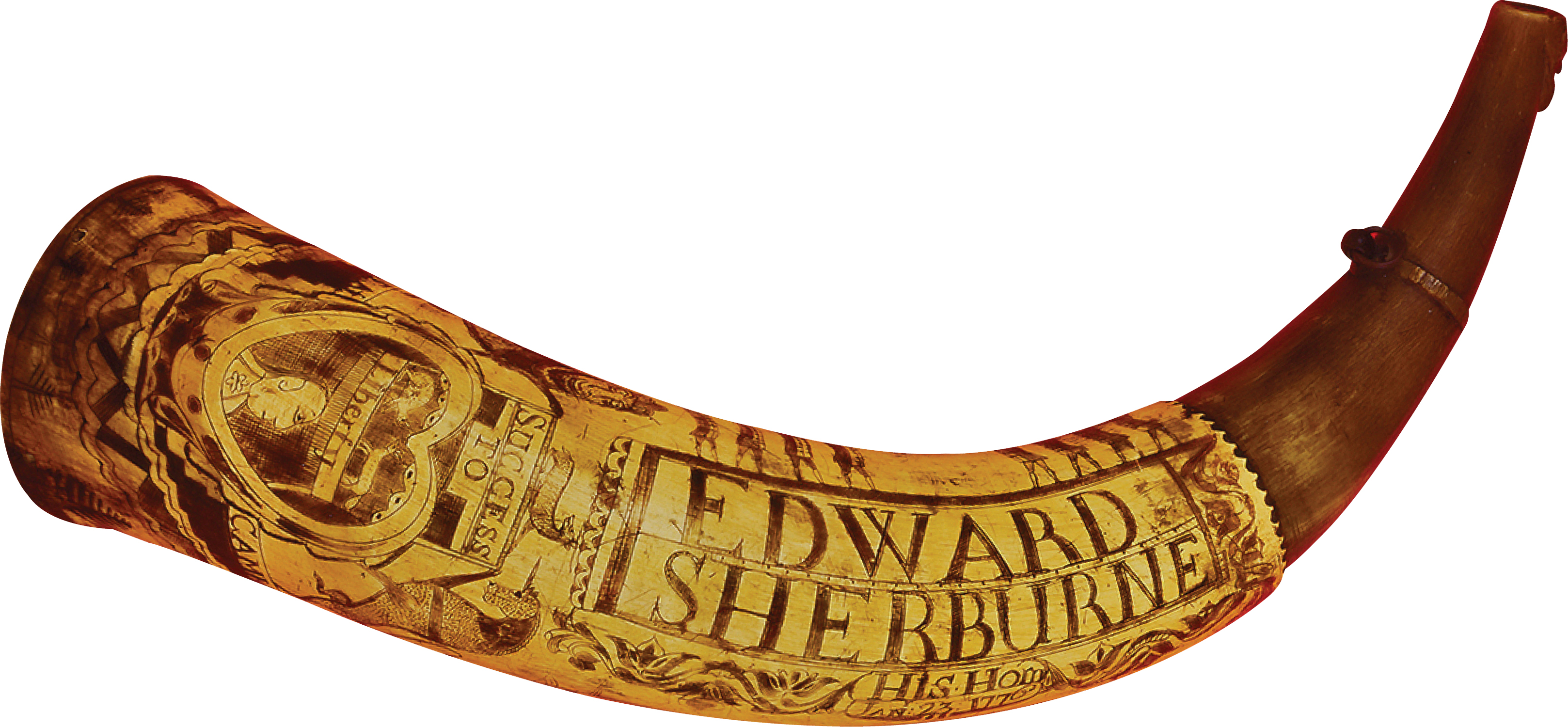

The two powder horns shown here are emblazoned with patriotic rhetoric about liberty. William Waller joined a Virginia militia unit in 1775 and defended New York against the British invasion in August 1776. He chose two slogans: “LIBERTY or DEATH” and, on the other side, “KILL or be KILLD.” The first had become something of a popular catchphrase in 1775; it graced the masthead of a fiery Massachusetts newspaper, and it also appeared in occasional personal correspondence. (Its usage did not originate with a March 1775 speech by Patrick Henry, alleged to end with the stirring words “Give me Liberty or Give me Death.” Henry’s speech was nowhere reported in the press of his day, nor did he speak from a written copy. A biographer in 1816 crafted the famous lines, based on a recollection of an old man present that day.) Waller carried his powder horn into a November 1776 battle defending Fort Washington, just north of New York City. The fort fell, and Waller was one of 3,000 men captured by the British that day. Most of those captives were herded into prison ships in the waters off New York City, and almost none of them survived.

SOURCES: Waller Powder Horn: Image courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution; Sherburne Powder Horn and Detail: Photo by David Wesbrook. Reprinted courtesy of the Honourable Company of Horners.

Questions for Analysis

- Why would soldiers put their names on their powder horns? How were the horns similar to military dog tags?

- What might the date on a powder horn signify about a soldier’s participation in the war? Why might it be important or useful to carry dated equipment?

- These two horns and many others carry military motifs and themes. Is it in any way surprising to find a lack of pictorial references to civilian life or loved ones back home?

Connect to the Big Idea

The scores of existing powder horns show us an intricate and often beautiful form of folk art. What can they also show us about the political beliefs and personally felt allegiances of the common soldier in the Revolutionary War?