Treason and Guerrilla Warfare

Britain’s southern strategy succeeded in 1780 in part because of information about American troop movements secretly conveyed by an American officer, Benedict Arnold. The hero of several American battles, Arnold was a deeply insecure man who never felt he got his due. Sometime in 1779, he opened secret negotiations with General Clinton in New York, trading information for money and hinting that he could deliver far more of value. When General Washington made him commander of West Point, a new fort on the Hudson River sixty miles north of New York City, Arnold’s plan crystallized. West Point controlled the Hudson; its capture by the British might well have meant victory in the war.

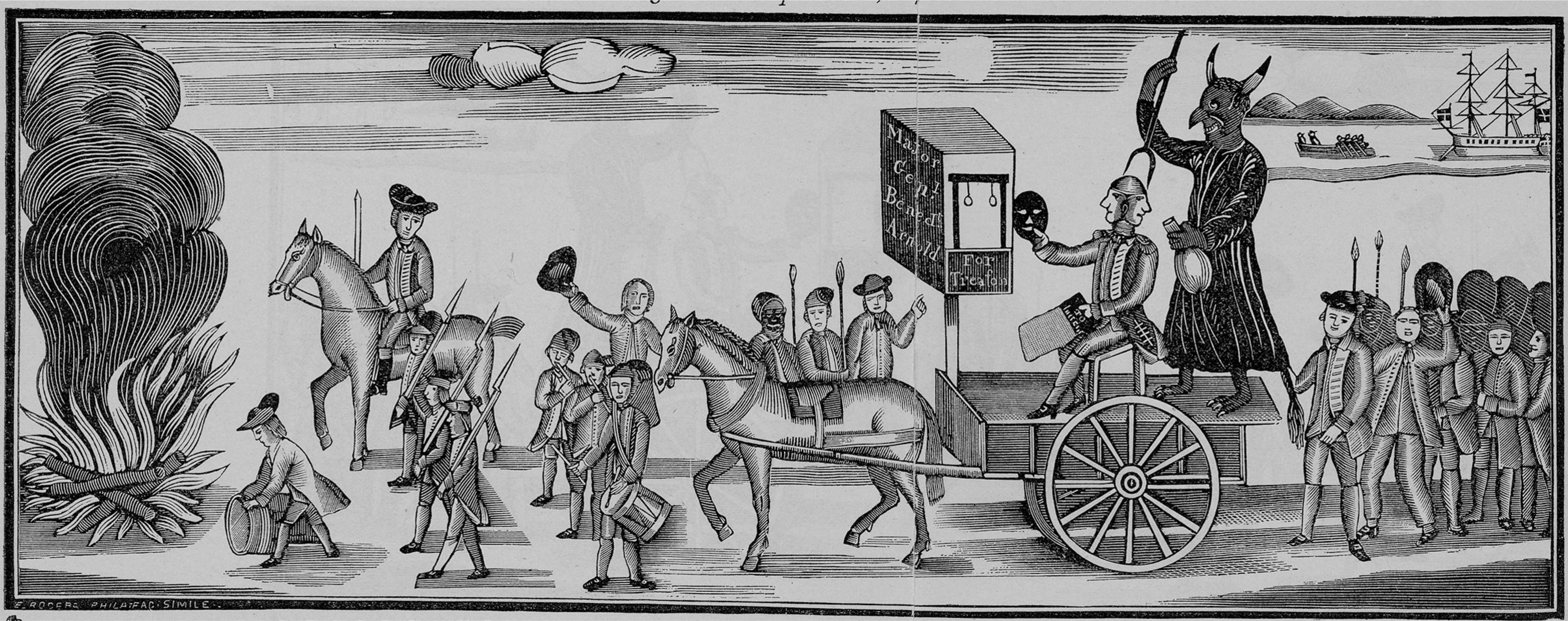

Arnold’s plot to sell a West Point victory to the British was foiled in the fall of 1780 when Americans captured the man carrying plans of the fort’s defense from Arnold to Clinton. News of Arnold’s treason created shock waves. Arnold represented all of the patriots’ worst fears about themselves: greedy self-

Shock over Gates’s defeat at Camden and Arnold’s treason revitalized rebel support in western South Carolina, an area that Cornwallis thought was pacified and loyal. The backcountry of the South soon became the site of guerrilla warfare. In hit-

The British southern strategy depended on sufficient loyalist strength to hold reconquered territory as Cornwallis’s army moved north. The backcountry civil war proved this assumption false. The Americans won few major battles in the South, but they ultimately succeeded by harassing the British forces and preventing them from foraging for food. Cornwallis moved the war into North Carolina in the fall of 1780 because the North Carolinians were supplying the South Carolina rebels with arms and men (see Map 7.4). Then news of a massacre of loyalist units by 1,400 frontier riflemen at the battle of King’s Mountain, in western South Carolina, sent him hurrying back. The British were stretched too thin to hold even two colonies.