The American Promise:

Printed Page 170

The American Promise Value

Edition: Printed Page 163

The Declaration of Independence

In addition to Paine’s Common Sense, another factor hastening independence was the prospect of an alliance with France, Britain’s archrival. France was willing to provide military supplies and naval power only if assured that the Americans would separate from Britain. News that the British were negotiating to hire German mercenary soldiers further solidified support for independence. By May 1776, all but four colonies were agitating for a declaration. The holdouts were Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, and South Carolina, the latter two containing large loyalist populations. An exasperated Virginian wrote to his friend in the congress, “For God’s sake, why do you dawdle in the Congress so strangely? Why do you not at once declare yourself a separate independent state?”

In early June, the Virginia delegation introduced a resolution calling for independence. The moderates still commanded enough support to postpone a vote on the measure until July. In the meantime, the congress appointed a committee, with Thomas Jefferson and others, to draft a longer document setting out the case for independence.

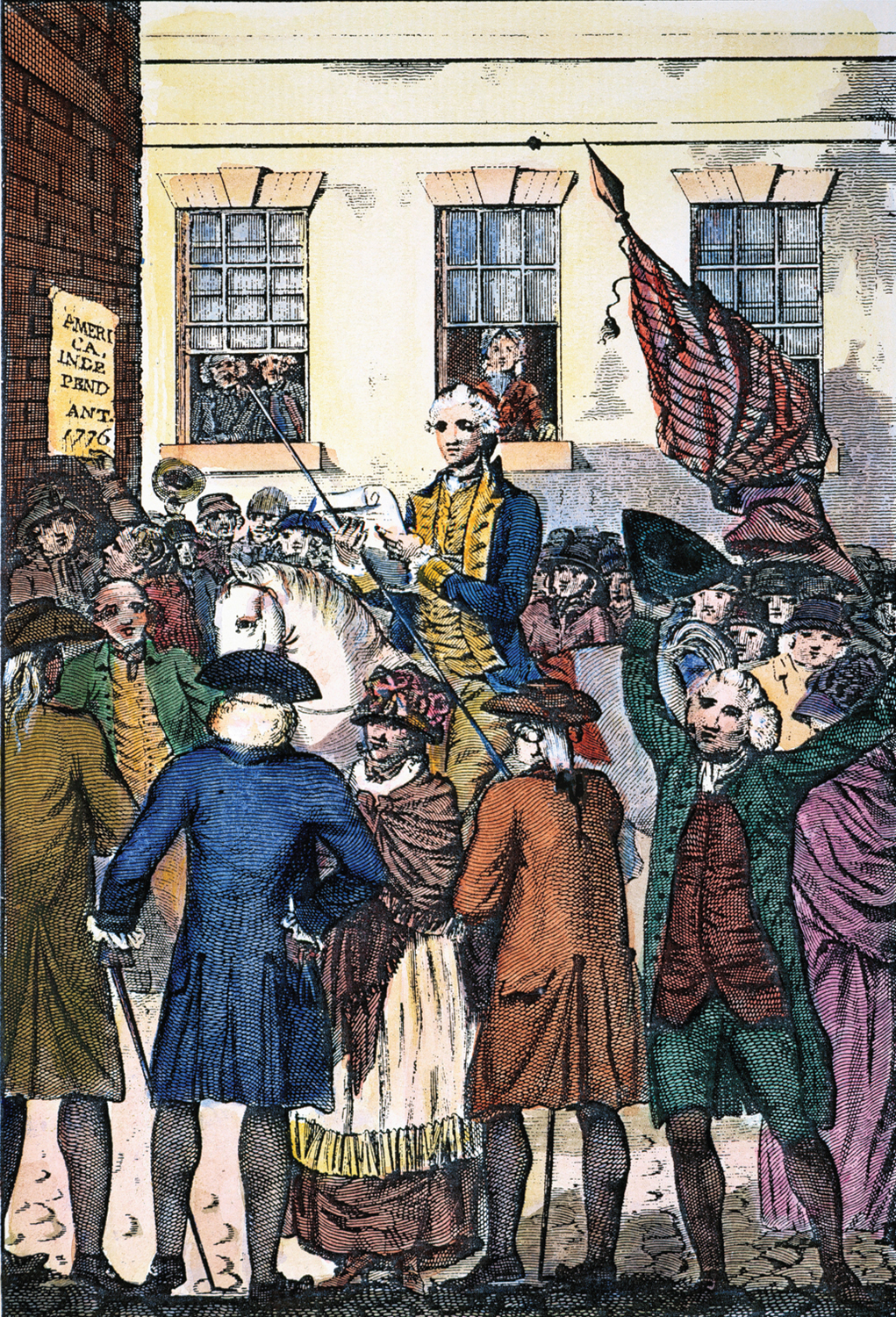

On July 2, after intense politicking, all but one state voted for independence; New York abstained. The congress then turned to the document drafted by Jefferson and his committee. Jefferson began with a preamble that articulated philosophical principles about natural rights, equality, the right of revolution, and the consent of the governed as the only true basis for government. He then listed more than two dozen specific grievances against King George. The congress passed over the preamble with little comment and instead wrangled over the list of grievances, especially the issue of slavery. Jefferson had included an impassioned statement blaming the king for slavery, which delegates from Georgia and South Carolina struck out, not wishing to denounce their labor system. But the congress let stand another of Jefferson’s grievances, blaming the king for mobilizing “the merciless Indian Savages” into bloody frontier warfare, a reference to Pontiac’s Rebellion (see “Pontiac’s Rebellion and the Proclamation of 1763” in chapter 6).

On July 4, the amendments to Jefferson’s text were complete, and the congress formally adopted the Declaration of Independence, with New York switching from abstention to approval ten days later, making the vote unanimous. In August, the delegates gathered to sign the official parchment copy. Four men, including John Dickinson, declined to sign; several others “signed with regret . . .

Printed copies did not include the signers’ names, for they had committed treason, a crime punishable by death. On the day of signing, they indulged in gallows humor. When Benjamin Franklin paused before signing, John Hancock of Massachusetts teased him, “Come, come, sir. We must be unanimous. No pulling different ways. We must all hang together.” Franklin replied, “Indeed we must all hang together. Otherwise we shall most assuredly hang separately.”

REVIEW Why were many Americans initially reluctant to pursue independence from Britain?