Writing Descriptions

Printed Page 543-551

Writing Descriptions

Technical communication often requires descriptions: verbal and visual representations of the physical or operational features of objects, mechanisms, and processes.

- Objects. An object is anything from a natural physical site, such as a volcano, to a synthetic artifact, such as a battery. A tomato plant is an object, as is an automobile tire or a book.

- Mechanisms. A mechanism is a synthetic object consisting of a number of identifiable parts that work together. A cell phone is a mechanism, as is a voltmeter, a lawnmower, or a submarine.

- Processes. A process is an activity that takes place over time. Species evolve; steel is made; plants perform photosynthesis. Descriptions of processes, which explain how something happens, differ from instructions, which explain how to do something. Readers of a process description want to understand the process; readers of instructions want a step-by-step guide to help them perform the process.

Descriptions of objects, mechanisms, and processes appear in virtually every kind of technical communication. For example, an employee who wants to persuade management to buy some equipment includes a description of the equipment in the proposal to buy it. A company manufacturing a consumer product provides a description and a photograph of the product on its website to attract buyers. A developer who wants to build a housing project includes in his proposal to municipal authorities descriptions of the geographical area and of the process he will use in developing that area.

Typically, a description is part of a larger document. For example, a maintenance manual for an air-conditioning system might begin with a description of the system to help the reader understand first how it operates and then how to fix or maintain it.

Before you begin to write a description, consider carefully how the audience and the purpose of the document will affect what you write. What does the audience already know about the general subject? For example, if you want to describe how the next generation of industrial robots will affect car manufacturing, you first have to know whether your readers understand the current process and whether they understand robotics.

Your sense of your audience will determine not only how technical your vocabulary should be but also how long your sentences and paragraphs should be. Another audience-related factor is your use of graphics. Less-knowledgeable readers need simple graphics; they might have trouble understanding sophisticated schematics or decision charts. As you consider your audience, think about whether any of your readers are from other cultures and might therefore expect different topics, organization, or writing style in the description.

Consider, too, your purpose. What are you trying to accomplish with this description? If you want your readers to understand how a personal computer works, write a general description that applies to several brands and sizes of computers. If you want your readers to understand how a specific computer works, write a particular description. A general description of personal computers might classify them by size, then go on to describe desktops, laptops, and tablets in general terms. A particular description, however, will describe only one model of personal computer, such as a Millennia 2500. Your purpose will determine every aspect of the description, including its length, the amount of detail, and the number and type of graphics.

There is no single organization or format used for descriptions. Because descriptions are written for different audiences and different purposes, they can take many shapes and forms. However, the following four suggestions will guide you in most situations:

- Indicate clearly the nature and scope of the description.

- Introduce the description clearly.

- Provide appropriate detail.

- End the description with a brief conclusion.

If the description is to be a separate document, give it a title. If the description is to be part of a longer document, give it a section heading. In either case, clearly state the subject and indicate whether the description is general or particular. For instance, a general description of an object might be entitled “Description of a Minivan,” and a particular description, “Description of the 2015 Honda Odyssey.” A general description of a process might be called “Description of the Process of Designing a New Production Car,” and a particular description, “Description of the Process of Designing the Chevrolet Malibu.”

Provide any information that readers need in order to understand the detailed information that follows. Most introductions to descriptions are general: you want to give readers a broad understanding of the object, mechanism, or process. You might also provide a graphic that introduces your readers to the overall concept. For example, for a process, you might include a flowchart summarizing the steps in the body of the description; for an object, such as a bicycle, you might include a photograph or a drawing showing the major components you will describe in detail in the body.

Table 20.1 shows some of the basic kinds of questions you might want to answer in introducing object, mechanism, and process descriptions. If the answer is obvious, simply move on to the next question.

| TABLE 20.1 Questions to Answer in Introducing a Description | |

| FOR OBJECT AND MECHANISM DESCRIPTIONS | FOR PROCESS DESCRIPTIONS |

|

|

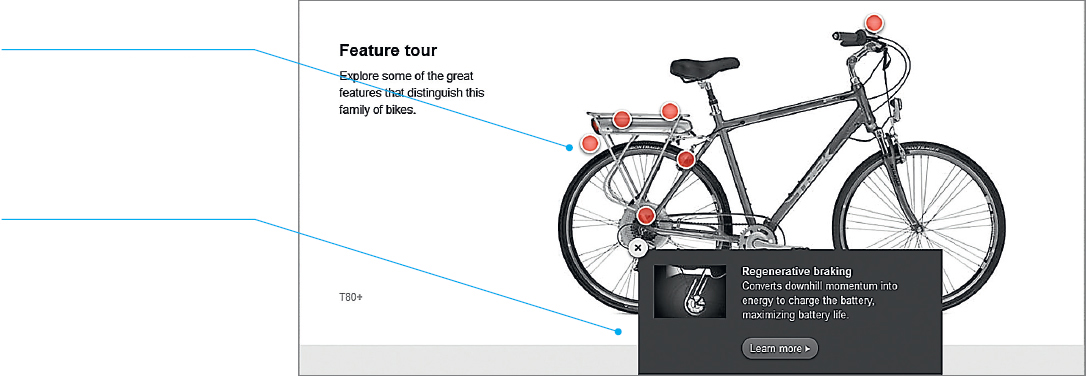

Figure 20.2 shows the introductory graphic accompanying a description of an electric bicycle.

Clicking on any of the red dots opens a window with a one-sentence description and graphic, as well as a link to an extended description and more-detailed graphic.

This web-based description includes six labeled systems. Here we see the expanded description of one of them: the regenerative braking system.

In the body of a description—the part-by-part or step-by-step section—treat each major part or step as a separate item. In describing an object or a mechanism, define each part and then, if applicable, describe its function, operating principle, and appearance. In discussing the appearance, include shape, dimensions, material, and physical details such as texture and color (if essential). Some descriptions might include other qualities, such as weight or hardness.

In describing a process, treat each major step as if it were a separate process. Do not repeat your answer to the question about who or what performs the action unless a new agent performs it, but do answer the other important questions: what the step is; what its function is; and when, where, and how it occurs.

A description can have not only parts or steps but also subparts or substeps. A description of a computer system includes a keyboard as one of its main parts, and the description of the keyboard includes the numeric keypad as one of its subparts. And the description of the numeric keypad includes the arrow keys as one of its subparts. The level of detail depends on the complexity of the item and the readers’ needs. The same principle applies in describing processes: if a step has substeps, you need to describe who or what performs each substep (if that is not obvious) as well as what the substep is, what its function is, and when, where, and how it occurs.

Providing Appropriate Detail in Descriptions

Use the following techniques to flesh out your descriptions.

FOR MECHANISM AND OBJECT DESCRIPTIONS

- Choose an appropriate organizational principle. Descriptions can be organized in various ways. Two organizational principles are common:

- — Functional: how the item works or is used. In a radio, the sound begins at the receiver, travels into the amplifier, and then flows out through the speakers.

- — Spatial: based on the physical structure of the item (from top to bottom, east to west, outside to inside, and so forth).

The description of a house, for instance, could be organized functionally (covering the different electrical and mechanical systems) or spatially (top to bottom, inside to outside, east to west, and so on). A complex description can use different patterns at different levels.

- Use graphics. Present a graphic for each major part. Use photographs to show external surfaces, drawings to emphasize particular items on the surface, and cutaways and exploded diagrams to show details beneath the surface. Other kinds of graphics, such as graphs and charts, are often useful supplements (see Chapter 12).

FOR PROCESS DESCRIPTIONS

- Structure the step-by-step description chronologically. If the process is a closed system—such as the cycle of evaporation and condensation—and therefore has no first step, begin with any principal step.

- Explain causal relationships among steps. Don’t present the steps as if they had nothing to do with one another. In many cases, one step causes another. In the operation of a four-stroke gasoline engine, for instance, each step creates the conditions for the next step.

- Use the present tense. Discuss steps in the present tense unless you are writing about a process that occurred in the historical past. For example, use the past tense in describing how the Snake River aquifer was formed: “The molten material condensed. . . .” However, use the present tense in describing how steel is made: “The molten material is then poured into . . . .” The present tense helps readers understand that, in general, steel is made this way.

- Use graphics. Whenever possible, use graphics to clarify each point. Consider flowcharts or other kinds of graphics, such as photographs, drawings, and graphs. For example, in a description of how a four-stroke gasoline engine operates, use diagrams to illustrate the position of the valves and the activity occurring during each step.

A typical description has a brief conclusion that summarizes it and prevents readers from overemphasizing the part or step discussed last.

A common technique for concluding descriptions of mechanisms and of some objects is to state briefly how the parts function together. At the end of a description of how the Apple iPhone touch screen works, for example, the conclusion might include the following paragraph:

When you touch the screen, electrical impulses travel from the screen to the iPhone processor, which analyzes the characteristics of the touch. These characteristics include the size, shape, and location of the touch, as well as whether you touched the screen in several places at once or moved your fingers. The processor then begins to process this data by removing any background noise and mapping and calculating the touch area or areas. Using its gesture-interpreting software, which combines these data with what it already knows about which function (such as the music player) you were using, the processor then sends commands to the music-player software and to the iPhone screen. How long does this process take? A nanosecond.

Like an object or mechanism description, a process description usually has a brief conclusion: a short paragraph summarizing the principal steps. Here, for example, is the concluding section of a description of how a four-stroke gasoline engine operates:

In the intake stroke, the piston moves down, drawing the air-fuel mixture into the cylinder from the carburetor. As the piston moves up, it compresses this mixture in the compression stroke, creating the conditions necessary for combustion. In the power stroke, a spark from the spark plug ignites the mixture, which burns rapidly, forcing the piston down. In the exhaust stroke, the piston moves up, expelling the burned gases.

For descriptions of more than a few pages, a discussion of the implications of the process might be appropriate. For instance, a description of the Big Bang might conclude with a discussion of how the theory has been supported and challenged by recent astronomical discoveries and theories.

A look at some sample descriptions will give you an idea of how different writers adapt basic approaches for a particular audience and purpose.

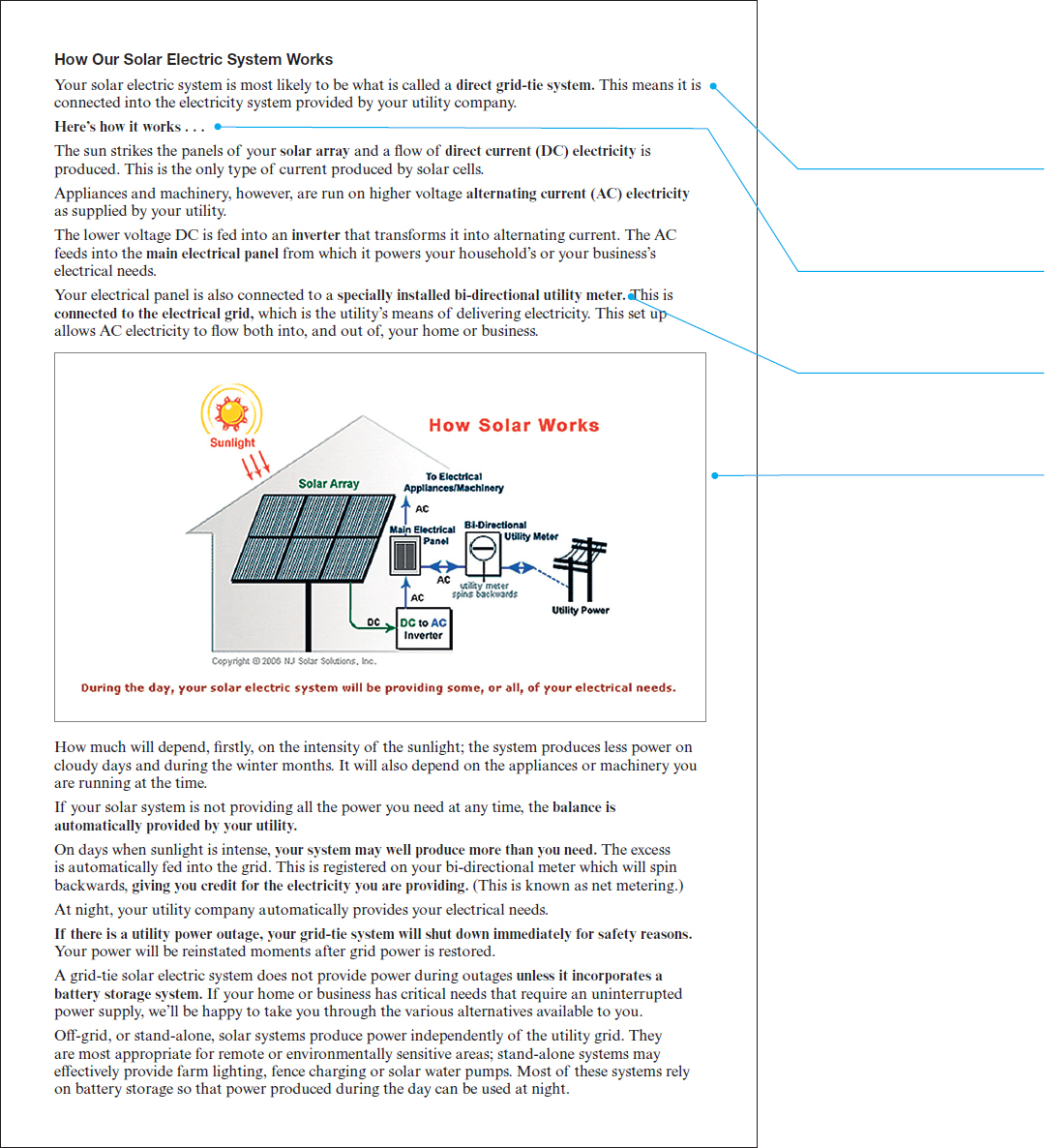

Figure 20.3 shows the extent to which a process description can be based on a graphic. The topic is a household solar array. The audience is the general reader.

This description begins with an informal definition of “direct gridtie system.”

In the next section, the writer presents the steps of the process in chronological order.

The description uses boldfaced text to emphasize key terms, most of which appear in the graphic.

The description focuses on the operating principle of the system. It does not seek to explain the details of how the system works. Accordingly, the graphic focuses on the logic of the process, not on the particulars of what the components look like or where they are located in the house.

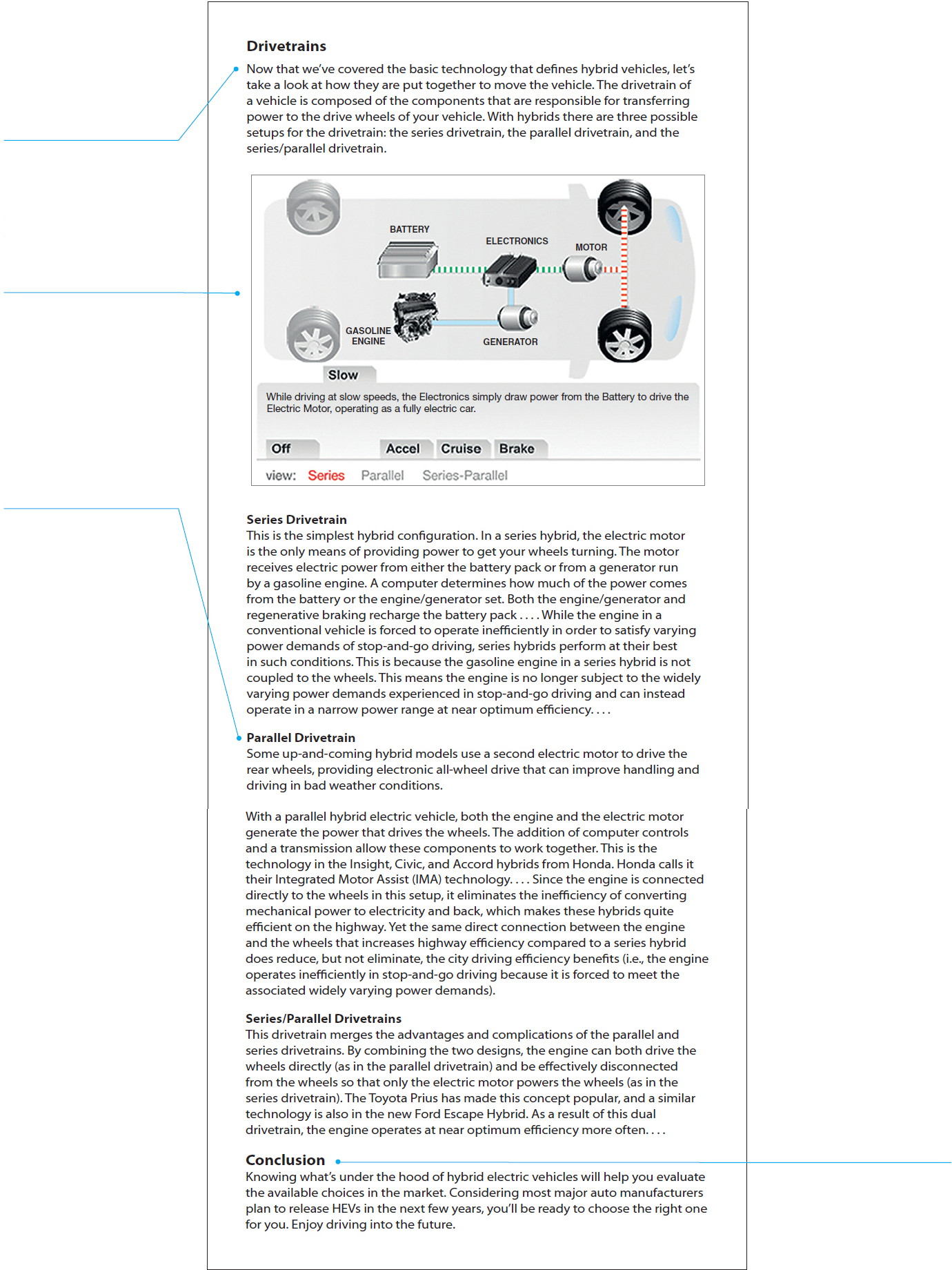

Figure 20.4 shows an excerpt from a mechanism description of three different types of hybrid drivetrains used in automobiles: series, parallel, and series/parallel.

This excerpt from a mechanism description begins with an advance organizer that helps the reader make the transition from the previous section (a basic description of hybrid technology) to the present section, which discusses the three types of drivetrains.

The interactive graphic enables the reader to view the principle of operation of three types of hybrid drivetrains, each during five modes. Here, the graphic shows how the components of the series drivetrain work together as the car operates at slow speeds. On the UCS website, the red and green striped lines are animated to highlight the components operating during the mode the reader has selected.

For each of the three types of drivetrains, the text begins with a description of the operating principle, followed by explanations of the strengths and weaknesses of the drivetrain. Notice that the audience and purpose of this description determine the kind of information it contains. Because this description seeks to explain the operating principle behind each of the three types of drivetrains, it focuses on the drivetrains’ functions, not on the materials they are made of or on their technical specifications.

This section of the description ends with a brief conclusion.

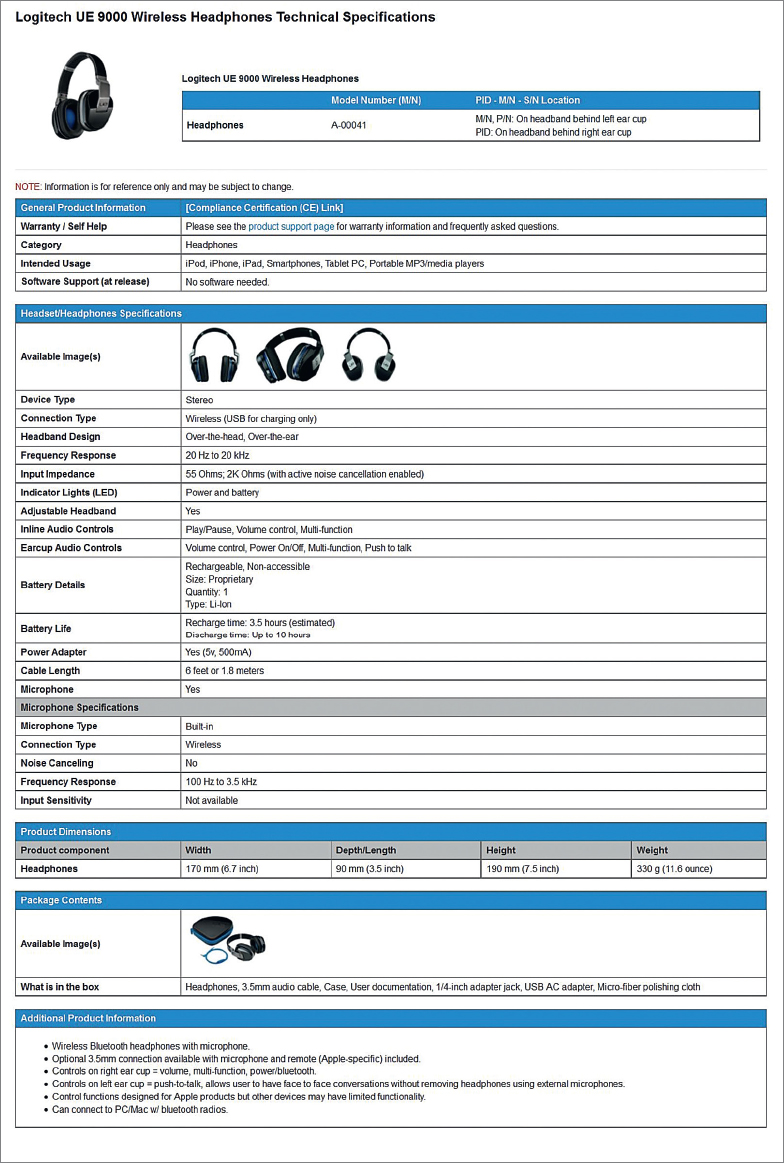

Figure 20.5 shows an excerpt from a set of specifications for Logitech headphones.

An important kind of description is called a specification. A typical specification (or spec) consists of a graphic and a set of statistics about the device and its performance characteristics. Specifications help readers understand the capabilities of an item. You will see specifications on devices as small as transistors and as large as aircraft carriers.

Because this web-based spec sheet accompanies a consumer product, the arrangement of the specs is geared toward the interests of the likely purchasers. The audio specs are presented before the power specs because potential purchasers of high-end headphones will be most interested in the sound quality.

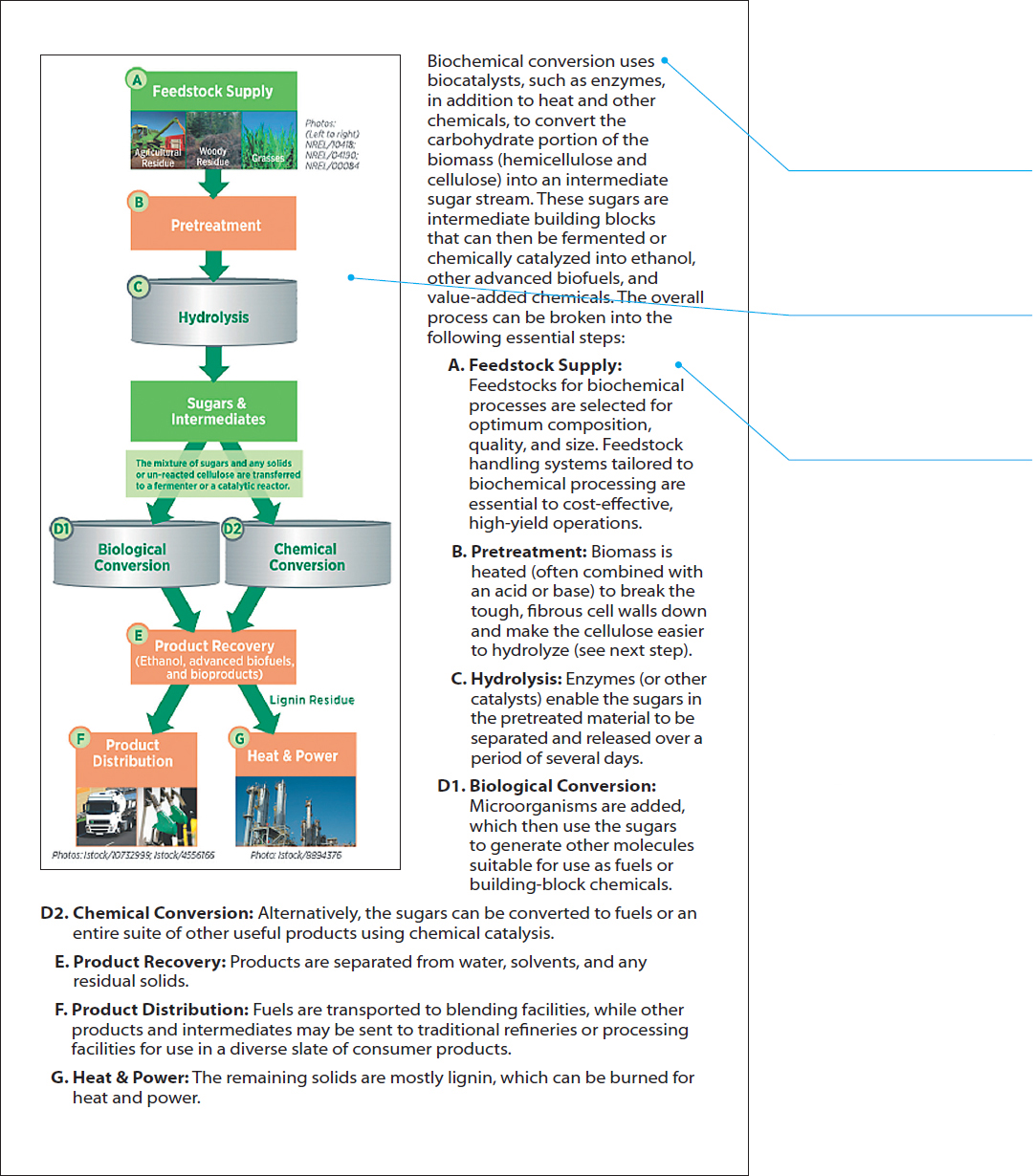

Figure 20.6 is a description of the process of turning biomass into useful fuels and other products.

This description begins with an overview of the process of biochemical conversion: the process of using fermentation and catalysis to make fuels and products.

The description includes a flowchart explaining the major steps in the process. The designers included photographs to add visual interest to the flowchart.

The lettered steps in the flowchart correspond to the textual descriptions of the steps in the process.

Most of the description is written in the passive voice (such as “Feedstocks for biochemical processes are selected . . .”). The passive voice is appropriate because the focus of this process description is on what happens to the materials, not on what a person does. By contrast, in a set of instructions the focus is on what a person does.