Narrating a Process

Process narratives explain how something was done or instruct readers on how it could or should be done. Whether the purpose is explanatory or instructional, process narratives must clearly convey each necessary action and the exact order in which the actions occur.

Use process narratives to explain.

Explanatory process narratives often relate particular experiences or elucidate processes followed by machines or organizations. Consider this excerpt from a remembered-

Temporal transitions and simple past-

The job seemed easy enough as I picked up bundle after bundle of tobacco and put it on the belt, careful to turn the knot end toward me so that it would be placed right to go under the cutting machine. Gradually, as we worked up our tobacco, I had to bend more, for as we emptied the hogshead we had to stoop over to pick up the tobacco, then straighten up and put it on the belt just right. Then I discovered the hard part of the job: the belt kept moving at the same speed all the time and if the leaves were not placed on the belt at the same tempo there would be a big gap where your bundle should have been. So that meant that when you got down lower, you had to bend down, get the tobacco, straighten up fast, make sure it was placed knot end toward you, place it on the belt, and bend down again. Soon you were bending down, up; down, up; down, up. All along the line, heads were bobbing—

—MARY MEBANE, “Summer Job”

Here, actions sequences (bend down, get the tobacco, straighten up fast) become a series of staccato movements (down, up; down, up; down, up) that emphasize the speed and machinelike actions Mebane had to take to keep up with the conveyor belt.

The next example shows how a laser printer functions:

Because the objects performing the action change from sentence to sentence, the writers must construct a clearly marked chain, introducing the object’s name in one sentence and repeating the name or using a synonym in the next.

To create a page, the computer sends signals to the printer, which shines a laser at a mirror system that scans across a charged drum. Whenever the beam strikes the drum, it removes the charge. The drum then rotates through a toner chamber filled with thermoplastic particles. The toner particles stick to the negatively charged areas of the drum in the pattern of characters, lines, or other elements the computer has transmitted and the laser beam mapped.

Once the drum is coated with toner in the appropriate locations, a piece of paper is pulled across a so-

—RICHARD GOLUB AND ERIC BRUS, Almanac of Science and Technology

Like Mebane’s process narrative, this one sequences the actions chronologically from beginning (“the computer sends signals to the printer”) to end (“fusing the toner to the paper”). Temporal transitions (then, once, then, final) and present-

EXERCISE 14.8

In Chapter 3, read paragraph 6 of Brian Cable’s profile of a local mortuary, “The Last Stop.” Here Cable narrates the process that the company follows once it has been notified of a client’s death. As you read, look for and mark the narrating strategies discussed in this chapter that Cable uses. Then reflect on how well you think the narrative presents the actions and their sequence.

Use process narratives to instruct.

For guidelines on designing documents, see Chapter 32.

Unlike explanatory process narratives,instructional process narratives must include all of the information a reader needs to perform the procedure presented. Depending on the reader’s experience, the writer might need to define technical terms, list tools that should be used, give background information, and account for alternatives or possible problems.

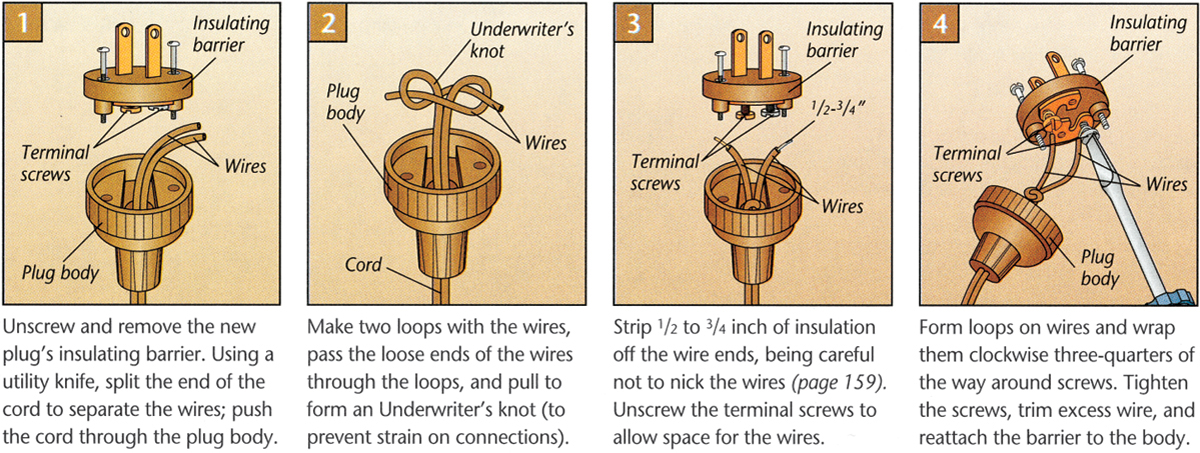

Figure 14.3 presents a detailed instructional process narrative from the Home Repair Handbook, which gives readers directions for replacing a broken plug. The first graphic includes four steps that are clearly numbered, illustrated, and narrated. Each step presents several actions to be taken, and its graphic shows what the plug should look like when these actions have been completed. We can identify the actions by looking at the verbs. Step 1 in “Replacing plugs with terminal screws,” for example, instructs readers to take four separate actions, each signaled by the verb (italicized here): “Unscrew and remove the new plug’s insulating barrier. Using a utility knife, split the end of the cord to separate the wires; push the cord through the plug body.” These are active verbs, and the sentences are in the form of clear and efficient commands. The anonymous authors do not assume that readers know very much, as they label every element of each drawing, including the screws. They also instruct readers precisely what to do. For example, in Step 4, they tell readers to “form loops on wires and wrap them clockwise three-

EXERCISE 14.9

Write a one-