Instructor's Notes

- The “Make Connections” activity can be used as a discussion board prompt by clicking on “Add to This Unit,” selecting “Create New,” choosing “Discussion Board,” and then pasting the “Make Connections” activity into the text box.

- The basic features (“Analyze and Write”) activities following this reading, as well as an autograded multiple-

choice quiz, a summary activity with a sample summary as feedback, and a synthesis activity for this reading, can be assigned by clicking on the “Browse Resources for the Unit” button or navigating to the “Resources” panel.

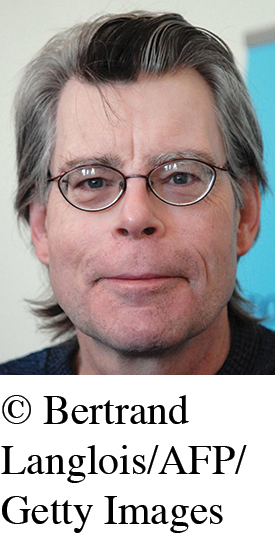

Stephen King Why We Crave Horror Movies

STEPHEN KING is America’s best-

In this classic essay, King analyzes why some of us love horror movies. As you read, consider the following:

What’s your feeling about horror films, roller coasters, or other scary rides? For you personally, what makes them attractive or something to avoid?

What reasons can you think of for why we like horror movies?

1

I think that we’re all mentally ill; those of us outside the asylums only hide it a little better — and maybe not all that much better, after all. We’ve all known people who talk to themselves, people who sometimes squinch their faces into horrible grimaces when they believe no one is watching, people who have some hysterical fear — of snakes, the dark, the tight place, the long drop . . . and, of course, those final worms and grubs that are waiting so patiently underground.

2

When we [see] a horror movie, we are daring the nightmare. Why? Some of the reasons are simple and obvious. To show that we can, that we are not afraid, that we can ride this roller coaster. Which is not to say that a really good horror movie may not surprise a scream out of us at some point, the way we may scream when the roller coaster twists through a complete 360 or plows through a lake at the bottom of the drop. And horror movies, like roller coasters, have always been the special province of the young; by the time one turns 40 or 50, one’s appetite for double twists or 360-

3

We also go to re-

4

And we go to have fun.

5

Ah, but this is where the ground starts to slope away, isn’t it? Because this is a very peculiar sort of fun, indeed. The fun comes from seeing others menaced — sometimes killed. One critic has suggested that if pro football has become the voyeur’s version of combat, then the horror film has become the modern version of the public lynching.

6

It is true that the mythic, “fairy tale” horror film intends to take away the shades of gray. . . .

7

If we are all insane, then sanity becomes a matter of degree. If your insanity leads you to carve up women like Jack the Ripper or the Cleveland Torso Murderer, we clap you away in the funny farm (but neither of those two amateur-

8

The potential lyncher is in almost all of us (excluding saints, past and present; but then, most saints have been crazy in their own ways), and every now and then, he has to be let loose to scream and roll around in the grass. Our emotions and our fears form their own body, and we recognize that it demands its own exercise to maintain proper muscle tone. Certain of these emotional muscles are accepted — even exalted — in civilized society; they are, of course, the emotions that tend to maintain the status quo of civilization itself. Love, friendship, loyalty, kindness — these are all the emotions that we applaud, emotions that have been immortalized in the couplets of Hallmark cards and in the verses (I don’t dare call it poetry) of Leonard Nimoy.

9

When we exhibit these emotions, society showers us with positive reinforcement; we learn this even before we get out of diapers. When, as children, we hug our rotten little puke of a sister and give her a kiss, all the aunts and uncles smile and twit and cry, “Isn’t he the sweetest little thing?” Such coveted treats as chocolate-

10

But anticivilization emotions don’t go away, and they demand periodic exercise. We have such “sick” jokes as “What’s the difference between a truckload of bowling balls and a truckload of dead babies?” (“You can’t unload a truckload of bowling balls with a pitchfork” . . . a joke, by the way, that I heard originally from a ten-

11

The mythic horror movie, like the sick joke, has a dirty job to do. It deliberately appeals to all that is worst in us. It is morbidity unchained, our most base instincts let free, our nastiest fantasies realized . . . and it all happens, fittingly enough, in the dark. For those reasons, good liberals often shy away from horror films. For myself, I like to see the most aggressive of them — Dawn of the Dead, for instance — as lifting a trap door in the civilized forebrain and throwing a basket of raw meat to the hungry alligators swimming around in that subterranean river beneath.

12

Why bother? Because it keeps them from getting out, man. It keeps them down there and me up here. It was Lennon and McCartney who said that all you need is love, and I would agree with that.

13

As long as you keep the gators fed.

[REFLECT]

Make connections: Media violence.

“The potential lyncher is in almost all of us,” says Stephen King, “. . . and every now and then, he has to be let loose to scream and roll around in the grass” (par. 8). King seems to say that horror films perform a social function by allowing us to exercise (or possibly exorcise) our least civilized emotions. In fact, King even argued against a proposed ban on the sale of violent video games to people under the age of eighteen.

To analyze King’s ideas about violence in the media, reflect on your own observation and personal experience with film, video games, or other media that may be considered violent. Your instructor may ask you to post your thoughts on a class discussion board or to discuss them with other students in class. Use these questions to get you started:

King asserts that we all have what he calls “anticivilization emotions” (par. 10). What does King give as an example of these emotions? What have you seen, heard, or felt that suggests you or others harbor such emotions?

The argument against violence in the media is basically that images of violence — or in the case of video games, performing virtual acts of violence —arouse anticivilization feelings and perhaps even inspire people (especially young people) to commit acts of real violence. King seems to agree that there is a cause-

effect relationship, but what does he think is the cause and the effect? What do you think? If you think media violence inspires real violence, do you support censorship of movies, television programs, books, or Internet sites that portray violence? If so, should this material be censored just for children or for all viewers? If you oppose outright censorship, do you support movie rating systems or the television V-

chip, which gives parents some control over what their children watch? Explain your responses.

[Analyze]

Use the basic features.

A WELL-

Writers try to present their subjects in an intriguing way that makes readers wonder about it. To do so, they typically frame or reframe their subjects, emphasizing new ways of looking at and understanding them. How does King make room for his less predictable causes and convince readers to go along for the ride?

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a couple of paragraphs analyzing and evaluating how King reframes his subject:

The title suggests that the subject of this essay is horror movies, but the key term in the title is the word “crave.” Look up the verb crave and the related noun craving to see what they mean. Also highlight some of the other words and phrases King associates with the appeal of horror movies, such as “mentally ill” and “hysterical fear” (par. 1). How do the words you highlighted relate to the word crave?

Given these key terms, how would you describe the way King reframes the subject for readers? How do these key terms enable him to plant the seed of his main idea at the very beginning of the essay?

A WELL-

In writing about horror movies, you might expect King to provide a lot of examples of the genre or to go into detail about one or two particularly memorable films. But, interestingly, King names only two films, neither of which is that memorable. By limiting the number and only referring to them briefly, King leaves a lot of space for readers to fill with their own favorite horror movies.

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a couple of paragraphs analyzing and evaluating the examples and comparisons King uses to support his argument and the films that come to mind for you:

In addition to horror movies, King gives several other examples. Find one or two of them, and consider how well they confirm his thesis that we all harbor anticivilization emotions.

King also compares horror movies to various other things, such as roller coasters (par. 2). Skim the essay, highlighting the comparisons King makes. Then, consider how they help support his causal argument.

Taken together, how effective are the examples and comparisons as support for King’s analysis? What examples did you think of as you read? How would the reading have been different had King supplied more examples of horror films?

AN EFFECTIVE RESPONSE: PUTTING ASIDE OBVIOUS CAUSES OR EFFECTS

People analyzing causes sometimes consider an array of possibilities before focusing on one or two serious probabilities. They may concede that these other causes or effects play some role, or they may simply dismiss them as trivial or irrelevant. “Some of the reasons,” King explicitly declares, “are simple and obvious” (par. 2).

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a couple of paragraphs analyzing and evaluating how well King uses concession and refutation:

Look closely at the causes King considers in the opening paragraphs to determine how he actually responds to them. For example, how does he support the assertion that some of them are “simple and obvious”? What other arguments, if any, does he use to refute them?

Given his purpose and audience, why do you think King chooses to begin by presenting reasons he thinks are simple and obvious?

A CLEAR, LOGICAL ORGANIZATION: USING CAUSE-

Writers of essays arguing for causes or effects sometimes rely on certain sentence strategies to present cause-

When .................... happens, .................... is the result.

If X does/says/acts like .................... , then Y will do/say/act like .................... .

| EXAMPLE | When we exhibit these emotions, society showers us with positive reinforcement; we learn this even before we get out of diapers. When, as children, we hug our rotten little puke of a sister and give her a kiss, all the aunts and uncles smile and twit and cry, “Isn’t he the sweetest little thing?” Such coveted treats as chocolate- |

Both of these sentence strategies establish a chronological relationship — one thing happens and then another thing happens. They also establish a cause-

ANALYZE & WRITE

Write a paragraph or two analyzing and evaluating how King uses these patterns elsewhere in this reading selection:

Skim the essay to find and mark the sentences that use these strategies. How do you know whether they each present a cause-

effect relationship as well as a chronological sequence? Why do you think King repeats these sentence strategies so often in this essay? Is this repetition an effective or ineffective strategy?

[RESPOND]

Consider possible topics: Popular culture.

Following King, you could consider writing about some aspect of popular culture. Consider, for example, why particular social networking sites, apps or video games, or genres of fiction or film are so popular with college students or other demographic groups. Why do ads appealing to sex work so well to sell cars and other consumer products? Why are negative political ads so effective?