Source 16.2

Representing the Declaration

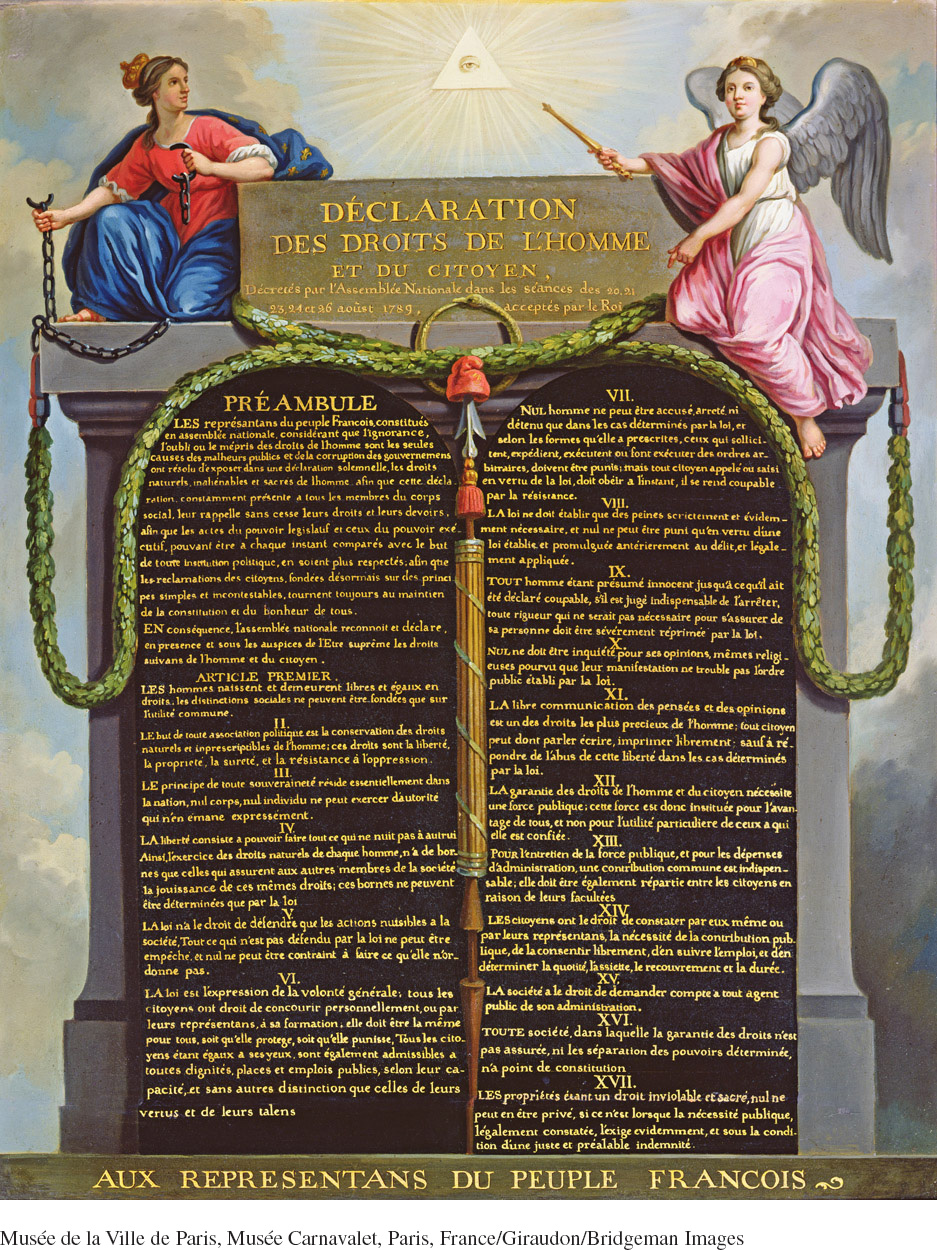

In the months that followed the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, the new authorities worked to spread the Declaration’s revolutionary ideas among the population. Perhaps the most iconic representation of the Declaration to appear in the months following its promulgation was a painting created by Jean-

Questions to consider as you examine the source:

- Why do you think that Le Barbier used well-

known figures, symbols, and imagery in his painting? Why did the artist adorn the image with only female figures? - What message is conveyed by placing the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen on tablets evoking the Ten Commandments?

- The whole composition is overseen by the eye of God the Creator radiating from a triangle that by the late eighteenth century had both biblical and Masonic connotations. What does this symbol add to the composition?

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen (Painting)