Source 1.2: Lascaux Rock Art

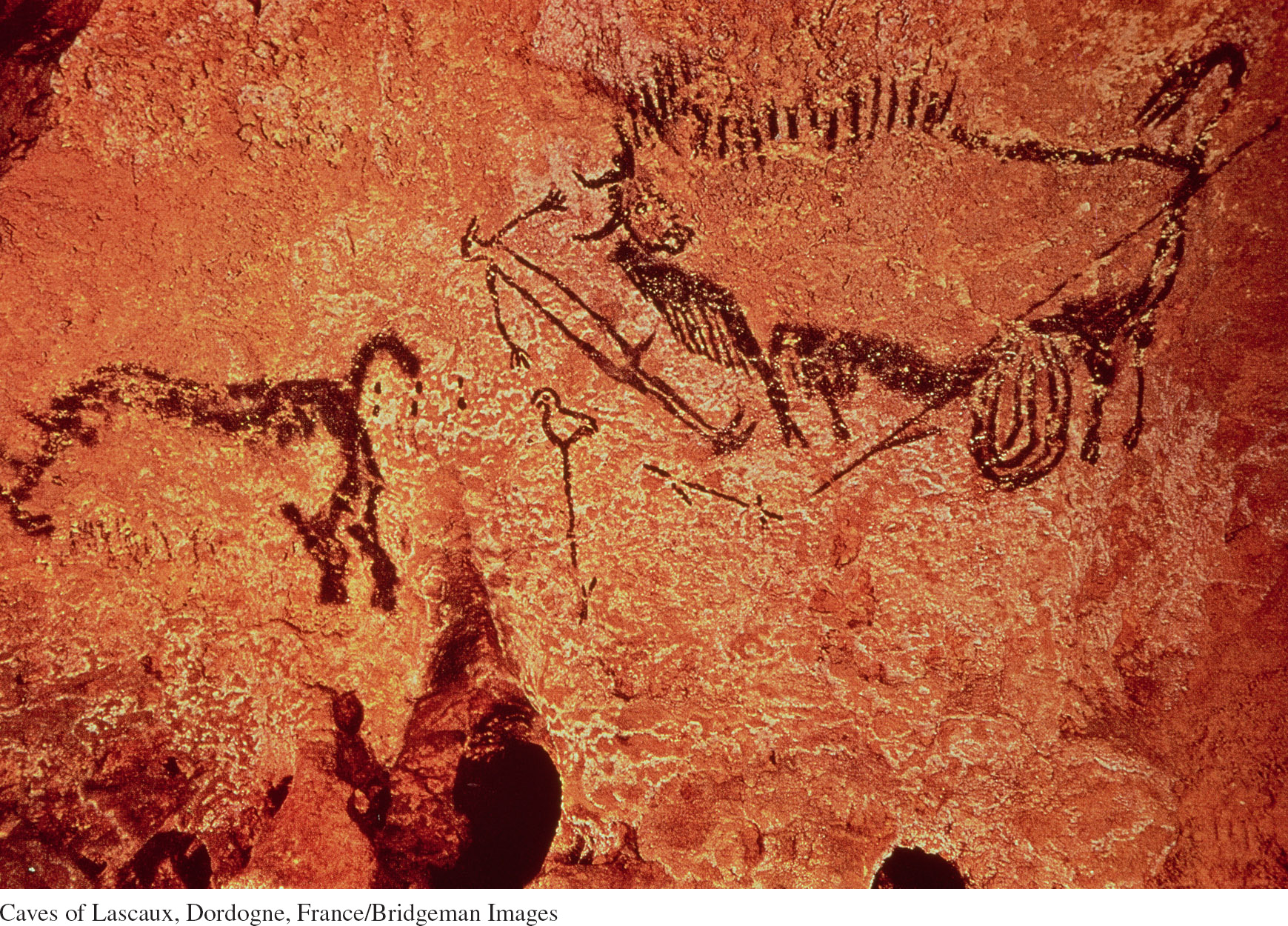

Physical remains studied by archeologists and others provide yet another point of entry into the history of nonliterate peoples. Among these, creative artistic representation has been especially useful, for it is as old as humankind itself, long preceding the emergence of urban civilizations. The most ancient of these artistic traditions are the rock paintings that Paleolithic people created all across the world.

Paleolithic art is found in many places, but perhaps the most well-

Scholars have debated endlessly what insights these remarkable images might provide into the mental world of Paleolithic Europeans. Were they examples of “totemic” thinking — the belief that particular groups of men and women were associated with, or descended from, particular animals? Did they represent “hunting magic” intended to enhance the success of these early hunters? Because many of the paintings were located deep within caves, were they perhaps part of religious or ritual practices or rites of passage? Were they designed to pass on information to future generations? Were the abstract designs star charts, as one scholar has suggested? Or did these images represent the visions of shamans, as some have also suggested for the South African rock painting in Chapter 1 of the main text. No one really knows.

But beyond their uncertain meaning as archeological evidence for Paleolithic life, modern humans have recognized the artistic value of the Lascaux paintings, appreciating their graceful lines, use of color, and distinctive sense of perspective and sometimes movement. Tradition has it that the great twentieth-

Click to see a virtual tour of the Lascaux caves created by the French government.

Questions to consider as you examine the source:

- No one knows for certain if the three figures in this image were painted at the same time. But if they were, it represents a very early narrative composition. How might you tell the story that the painting depicts? Is the man dead or wounded? What message would such a story convey?

- What differences do you notice between the portrayal of the human figure and that of the animals?

Lascaux Rock Art

Notes

- Gregory Curtin, The Cave Painters (New York: Random House, 2006), 96.