Source 2.2

The Standard of Ur

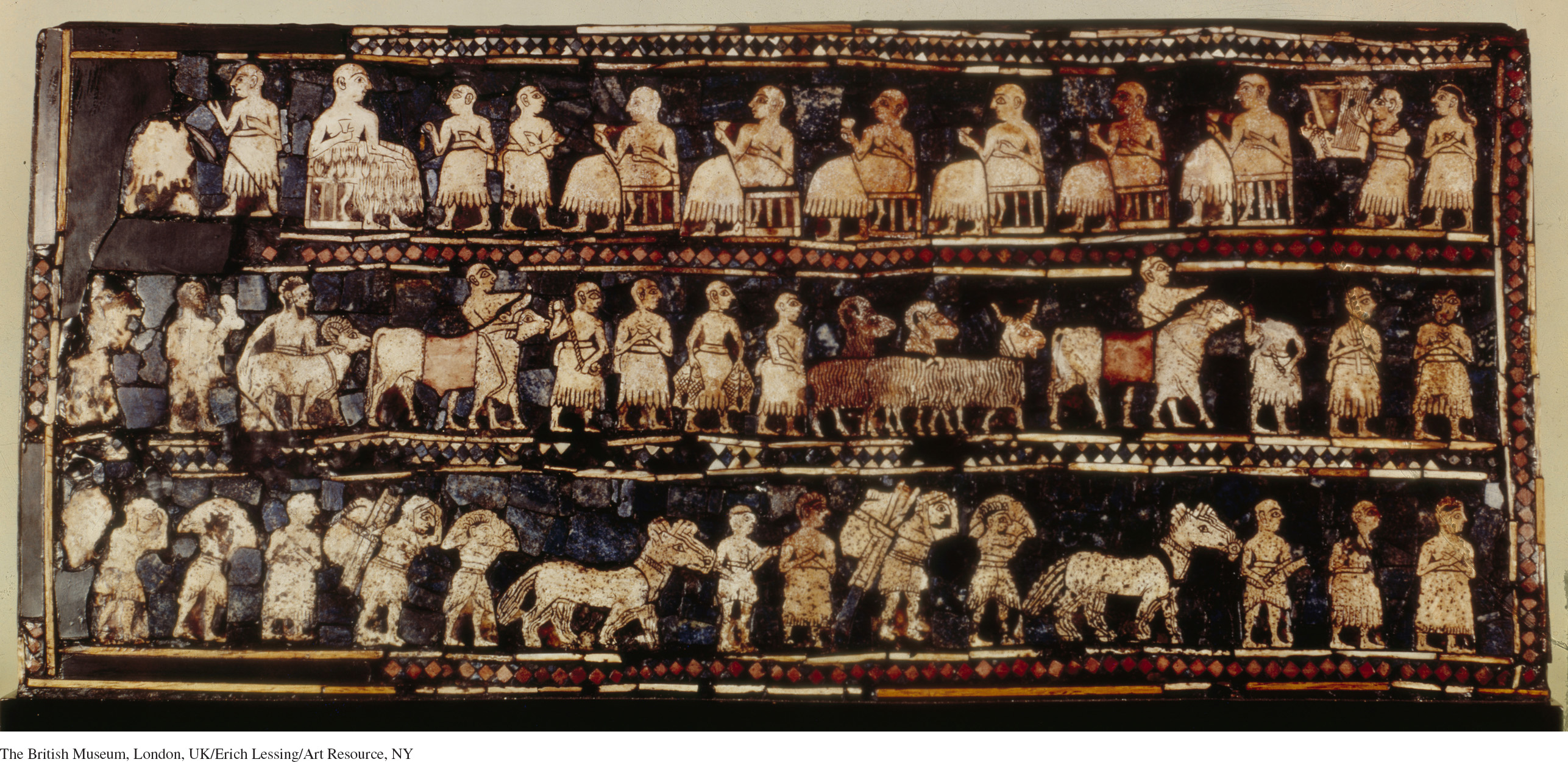

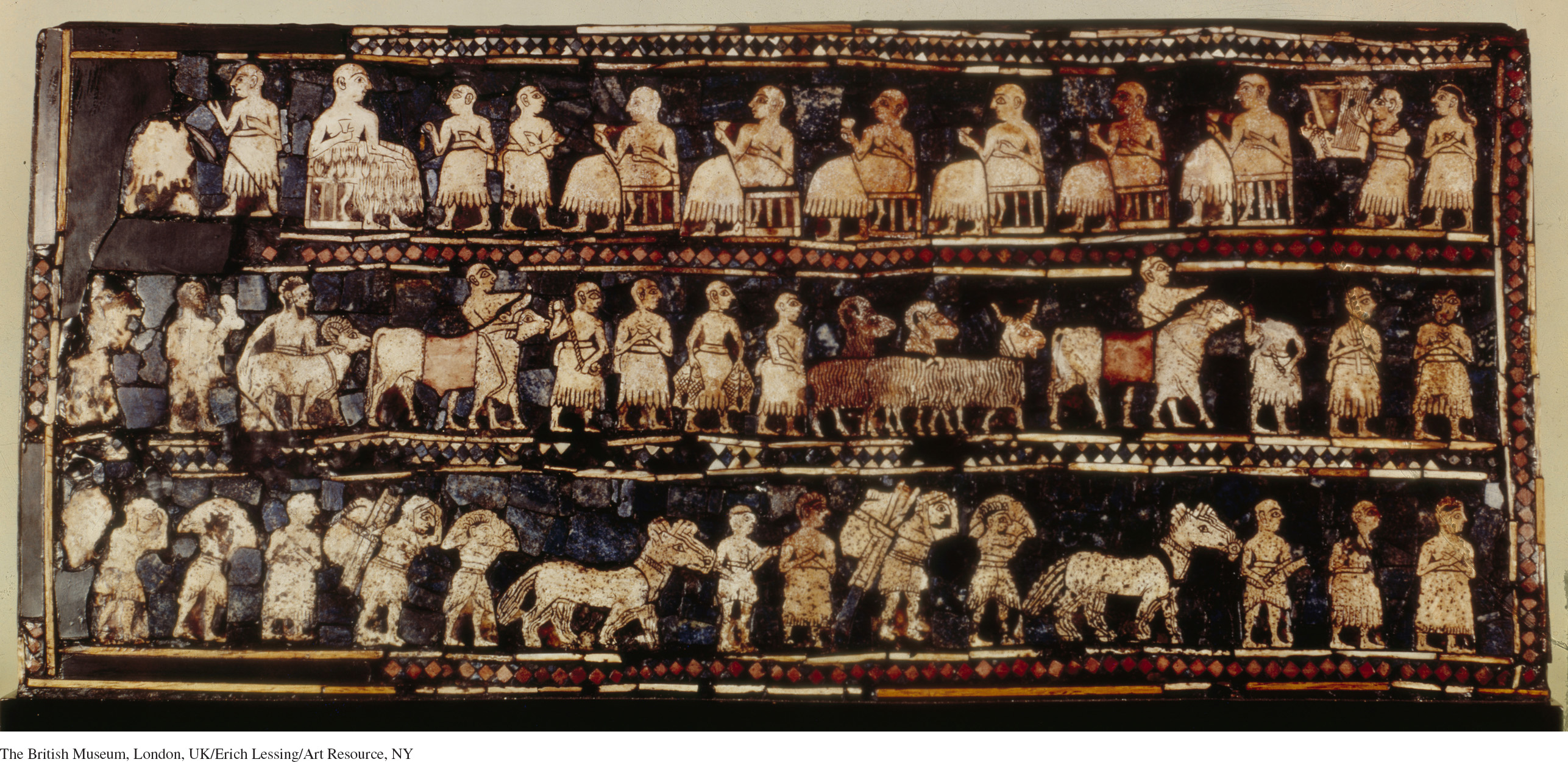

One of the most compelling visual illustrations of ancient Mesopotamian society comes from an artifact known as the Standard of Ur. Found in a large cemetery in the Sumerian city of Ur in what is now southern Iraq, the Standard is in fact a wooden box with elaborate inlaid mosaics on two sides, each of which has three panels, or registers. It dates to about 2500 B.C.E. No one knows why it was created or what use was made of it, but for historians it has become a vivid image of Mesopotamian social life.

Each side of the Standard tells its own story. One side, often called the “peace side,” depicts a prosperous, well-ordered, and very hierarchical society, in which the class differences of civilizations are sharply drawn. The upper class feasts, while the commoners offer the products of their labor. Such was the way of civilization. The other side, or “war side,” of the Standard illustrates yet another aspect of Mesopotamian society, for the many wars of Mesopotamian cities and empires generated prisoners who often became slaves.

Questions to consider as you examine the source:

- What distinct occupational roles can you identify in these images?

- What major social distinctions might be inferred from the Standard of Ur?

- What other information might historians derive from this artifact?

The Standard of Ur, Peace Panel

Standard of Ur, peace panelThe bottom two registers show commoners parading their agricultural produce and their animals, perhaps bringing tribute to the ruler and his entourage. The king is shown seated at the far left of the top register, in company with several servants and six seated members of the elite, each holding a raised cup. On the far right, a man is playing the lyre, perhaps accompanying a singer at the end.The British Museum, London, UK/Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY

The Standard of Ur, War Panel

Standard of Ur, war panelThe top register shows the king, large enough that his head penetrates the decorative border, standing in front of his leading warriors and his chariot. To his right stand the defeated prisoners, naked, bound, and bloody from their wounds. The middle register shows a battle scene and more prisoners, while the bottom panel presents war chariots trampling the defeated enemy.The British Museum, London, UK/Album/Art Resource, NY