Source 8.4: Japanese Zen Buddhism

Among Japan’s imports from China, none has been received more eagerly and thoroughly than Buddhism. And among the various forms of Buddhism, none have become more Japanese than Zen, which was becoming firmly established in Japan by the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Like all Buddhist teachings, it offered a path to the end of suffering, or to enlightenment. But for Zen practitioners, nothing external, such a deities or sacred texts, is of much help. Rather, the key practice is an inward-looking meditation, conducted under the guidance of often stern and rigorous teachers who were linked to a long lineage of transmission. In a classic formulation of Zen, there is “no dependence on words and letters; direct pointing to the mind of man; seeing into one's nature and attaining Buddhahood.” In this way, individuals come to realize that they are already enlightened, that they already possess a Buddha nature. Sometimes this occurs gradually, but at other times it occurs in a flash of insight while doing something ordinary such as catching a shrimp or cutting a piece of bamboo. Thus Zen emphasized simplicity, spontaneity, and the profundity of the ordinary, and it led to compassion and tranquility, amid all the changing and difficult circumstances of life.

Zen became associated in particular with the samurai, who appreciated its emphasis on rigorous practice and intuitive action. It also informed much of Japanese secular culture, especially painting, poetry, theater, and the elaborate simplicity of the tea ceremony.

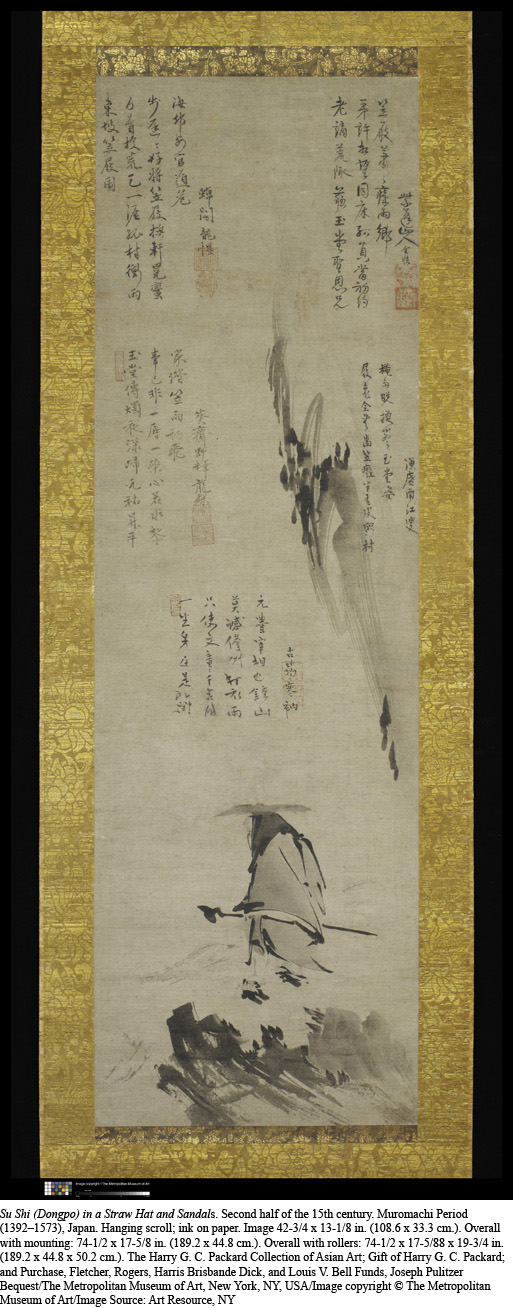

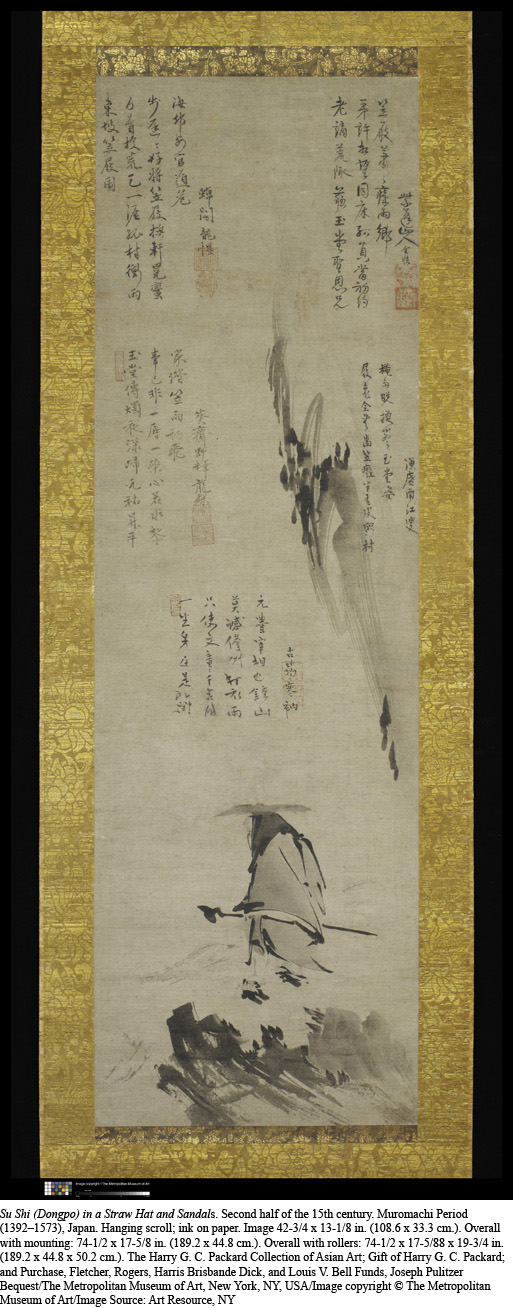

In this image by an unknown Japanese artist from the second half of the fifteenth century, something of the style and substance of Zen finds expression. With a few quick and simple brushstrokes, the artist set the scene of a story about a famous Chinese scholar-official named Su Dongpo, living in exile, caught in a sudden rainstorm, and forced to borrow a peasant’s straw hat and wooden sandals. While local people laughed uproariously at the sight of a highly educated scholar in peasant attire, Su himself remained calm and unperturbed. The poetic text in the image reflected the Zen conception of “the essential oneness of all things, good and bad, whether in office or in lonely exile.”3

Questions to consider as you examine the source:

- What significance do you see in a Japanese Zen artist’s referencing the story of a Chinese scholar?

- What distinctive features of a Zen Buddhist outlook are expressed in this image of a solitary figure?

- Why might members of the samurai class be attracted to such images and teachings?

Su Dongpo in Straw Hat and Wooden Shoes

Su Dongpo in Straw and Wooden ShoesSu Shi (Dongpo) in a Straw Hat and Sandals. Second half of the 15th century. Muromachi Period (1392–1573), Japan. Hanging scroll; ink on paper. Image 42-3/4 x 13-1/8 in. (108.6 x 33.3 cm.). Overall with mounting: 74-1/2 x 17-5/8 in. (189.2 x 44.8 cm.). Overall with rollers: 74-1/2 x 17-5/88 x 19-3/4 in. (189.2 x 44.8 x 50.2 cm.). The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art; Gift of Harry G. C. Packard; and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbande Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest/The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, USA/Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Image Source: Art Resource, NY

- “Su Dongpo in Straw Hat and Wooden Shoes,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed May 26, 2015, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1975.268.39.