Sources 20.1: Experiences on the Battlefront

“Bombardment, barrage, curtain-

Questions to consider as you examine the sources:

- What insights about the experience of fighting in World War I might you derive from these sources?

- What do they convey about the impact of the war on the outlook of these men?

- To what extent do these sources reveal the horrors of war in general, and in what ways do they reflect the distinctive features of World War I?

Source 20.1A

Julian Grenfell

Letter from a British Officer in the Trenches, November 18, 1914

They had us out again for 48 hours [in the] trenches. . . .

[We are] in a dripping sodden wood, with the German trench in some places 40 yards ahead. . . .

[Something similar happened the next day.] I went back at a sort of galloping crawl to our lines and sent a message to the 10th that the Germans were moving up their way in some numbers. Half an hour afterward, they attacked the 10th and our right, in massed formation, advancing slowly to within 10 yards of the trenches. We simply mowed them down. It was rather horrible.

Source: Laurence Housman, ed., War Letters of Fallen Englishmen (London: E. P. Dutton, 1930), 119–

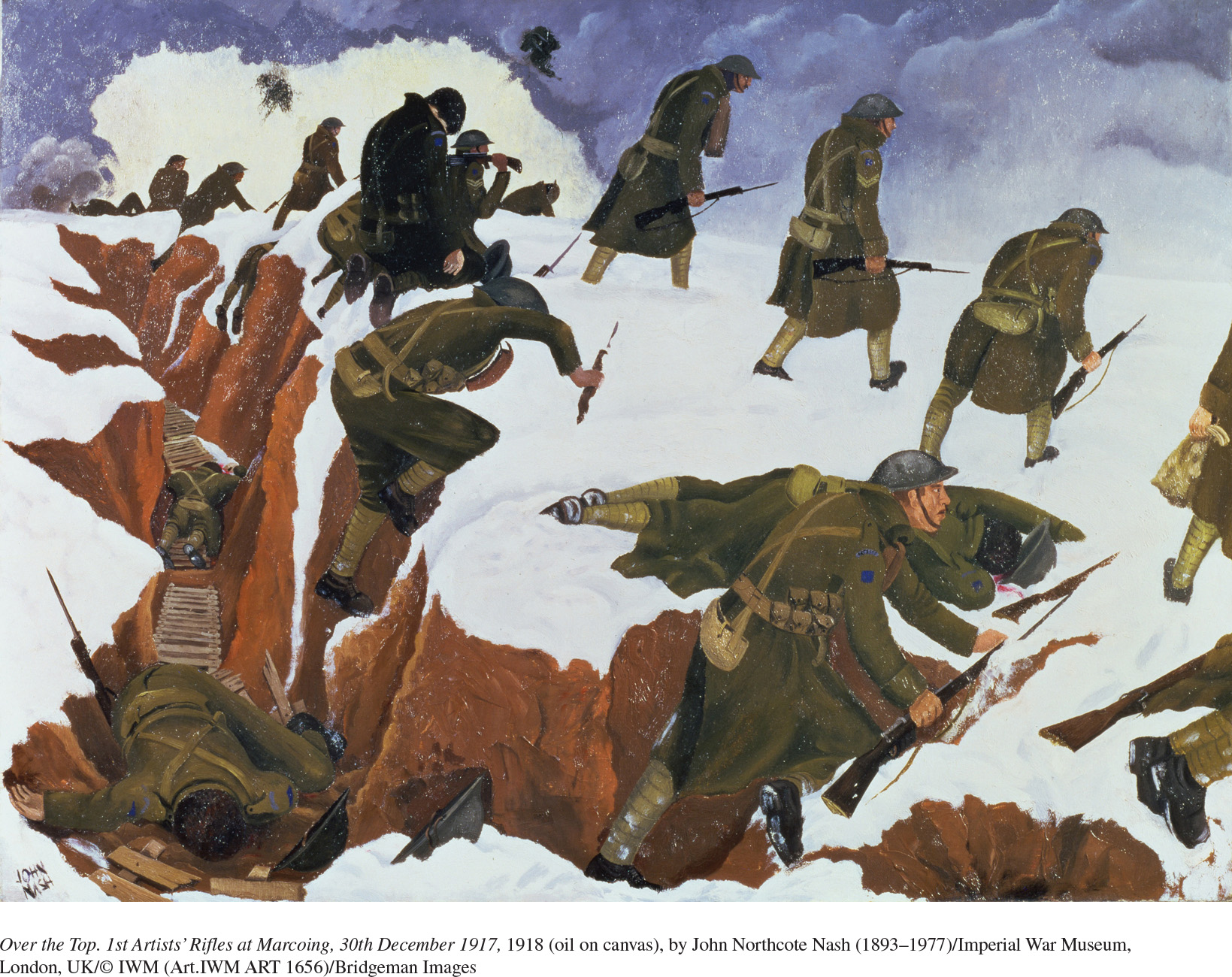

Source 20.1B

John Nash

Over the Top, 1918

Source 20.1C

Hugo Mueller

Letter from a German Soldier on the Western Front, 1915

It has been extremely interesting to study the contents of the letter-

War hardens one’s heart and blunts one’s feelings, making a man indifferent to everything that formerly affected and moved him; but these qualities of hardness and indifference towards fate and death are necessary in the fierce battle to which trench warfare leads. Anybody who allowed himself to realize the whole tragedy of some of the daily occurrences in our life here would either lose his reason or be forced to bolt across the enemy’s trench with his arms high in the air.

Source: Philipp Witkop, ed., German Students’ War Letters, translated by Anne F. Wedd (London: Methuen, 1929), 278–

Source 20.1D

Behari Lal

Letter from a Soldier in the British Indian Army, 1917

There is no likelihood of our getting rest during the winter. I am sure German prisoners could not be worse off in any way than we are. I had to go three nights without sleep, as I was on a motor lorry, and the lorry fellows, being Europeans, did not like to sleep with me, being an Indian. [The] cold was terrible, and it was raining hard; not being able to sleep on the ground in the open, I had to pass the whole night sitting on the outward lorry seats. I am sorry the hatred between Europeans and Indians is increasing instead of decreasing, and I am sure that the fault is not with the Indians. I am sorry to write this, which is not a hundredth part of what is in mind, but this increasing hatred and continued ill-

Source: David Omussi, ed., Indian Voices of the Great War (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999), 336–