CLINICAL INSIGHT

CLINICAL INSIGHTThe Conversion of Proto-oncogenes into Oncogenes Disrupts the Regulation of Cell Growth

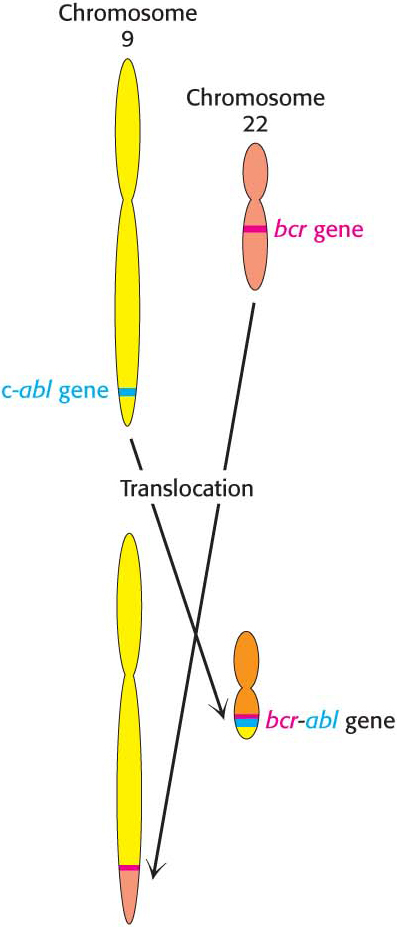

Genes that, when mutated, cause cancer often normally regulate cell growth. The unmutated, normally expressed versions of these genes are termed proto-oncogenes, and the proteins encoded by them are often signal-transduction proteins that regulate cell growth. If a proto-oncogene suffers a mutation that leads to unrestrained growth by the cell, the gene is then referred to as an oncogene (from the Greek onco, meaning “swelling,” “mass,” or “tumor”).

The gene encoding Ras, a component of the EGF-initiated pathway, is one of the genes most commonly mutated in human tumors. Mammalian cells contain three Ras proteins (H-, K-, and N-Ras), each of which cycles between inactive GDP and active GTP forms. The most common mutation in tumors is a loss of the intrinsic GTPase activity. Thus, the Ras protein is trapped in the “on” position and continues to stimulate cell growth, even in the absence of a continuing signal.

Mutated, or overexpressed, receptor tyrosine kinases also are frequently observed in tumors. For instance, the epidermal-growth-factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in some colorectal and head and neck cancers. Because some small amount of the receptor can dimerize and activate the signaling pathway even without binding to EGF, the overexpression of the receptor increases the likelihood that a “grow and divide” signal will be inappropriately sent to the cell. This understanding of cancer-related signal-transduction pathways has led to a therapeutic approach that targets the EGFR. Antibodies, such as cetuximab (Erbitux), have been generated that inhibit the EGFR by competing with EGF for the binding site on the receptor while also blocking the change in conformation that causes dimerization. The result is that the EGFR-controlled pathway is not initiated.

Page 240

Other genes can contribute to cancer development only when both copies of the gene normally present in a cell are deleted or otherwise damaged. Such genes are called tumor-suppressor genes. These genes encode proteins that either inhibit cell growth by turning off growth-promoting pathways or trigger the death of tumor cells. For example, genes for some of the phosphatases that participate in the termination of EGF signaling are tumor suppressors. Without any functional phosphatase present, EGF signaling persists after its initiation, stimulating inappropriate cell growth.

CLINICAL INSIGHT

CLINICAL INSIGHT

CLINICAL INSIGHT

CLINICAL INSIGHT