346

EARTHQUAKES

What Is an Earthquake?

What Is an Earthquake? How Do We Study Earthquakes?

How Do We Study Earthquakes? Earthquakes and Patterns of Faulting

Earthquakes and Patterns of Faulting Earthquake Hazards and Risks

Earthquake Hazards and Risks Can Earthquakes Be Predicted?

Can Earthquakes Be Predicted?

347

EARTHQUAKES RIVAL ALL OTHER natural disasters in the threat they pose to human life and property. Our fragile “built environment” is necessarily anchored in Earth’s active crust, which makes it extremely vulnerable to earthquakes and their secondary effects, such as ground ruptures, landslides, and tsunamis. Some events of the past century are sobering illustrations of this fact.

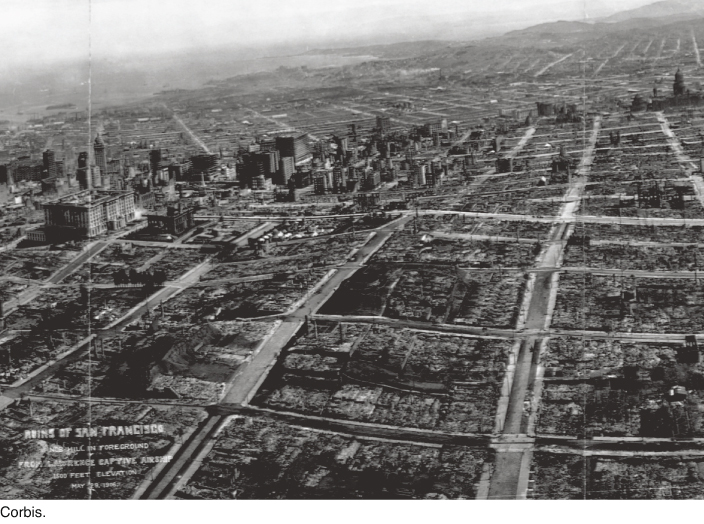

On a fine April morning in 1906, the citizens of northern California were awakened by the roar and violent shaking caused by the breaking of the San Andreas transform fault, which created the most destructive earthquake the United States has yet experienced. The ensuing fires destroyed the city of San Francisco; by the time the flames died away, nearly 3000 of its inhabitants were dead (Figure 13.1).

Almost a century later, on December 26, 2004, a much larger fault—a subduction-zone megathrust—broke west of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, lifting up the seafloor and sending a huge tsunami across the Indian Ocean. This monster wave drowned more than 220,000 people living on coastlines from Thailand to Africa. Another megathrust ruptured off Japan on March 11, 2011, creating an even larger tsunami, pictured here, that drowned almost 20,000. Between the 1906 earthquake and now, earthquakes have killed more than 2 million people around the world.

To cope with the all-too-frequent death and destruction caused by earthquakes, we have long sought to improve our ability to predict where and when these events might occur and our understanding of what happens when they do. Science has shown that seismic activity can be understood in terms of the basic machinery of plate tectonics. As a result, attempts to reduce earthquake risk have become increasingly fused with the quest for a more fundamental understanding of the geologically active Earth.

348

This chapter will examine what happens during earthquakes, how scientists use seismic waves to locate and measure earthquakes, and what can be done to reduce the casualties and economic damage caused by earthquakes. We cannot yet reliably predict when large earthquakes will occur, but we can take measures to reduce their destructiveness. We can use our geologic knowledge to identify places where large earthquakes are likely; work with engineers to design buildings, dams, bridges, and other structures that can withstand seismic shaking; and help endangered communities prepare for and respond to seismic events.