Earthquake Early Warning Systems

With the technology just described, it is possible to detect earthquakes in the early stages of fault rupture, rapidly predict the intensity of the future ground motions, and warn people before they experience the intense shaking that that might be damaging. Earthquake early warning systems detect strong shaking near an earthquake’s epicenter and transmit alerts ahead of the seismic waves. Potential warning times depend primarily on the distance between the user and the earthquake epicenter. There is a “blind zone” near an earthquake epicenter where early warning is not feasible, but at more distant sites, warnings can be issued from a few seconds up to about one minute prior to strong ground shaking.

Earthquake early warning systems have already been deployed in at least 5 countries—Japan, Romania, Taiwan, and Turkey—and a prototype system is being developed in the United States. Japan is the only country with a nationwide system that provides public alerts. A national seismic network of nearly 1000 seismographs is used to detect earthquakes and issue warnings, which are transmitted via the Internet, satellite, cell phones, as well as automated control systems that do such things as stop trains and place sensitive equipment in a safe mode. Earthquake early warning systems are being developed in the states of California and Washington, but their full deployment has not yet been funded by the U.S. Congress or state legislatures.

Tsunami Warning Systems

The great tsunamis generated by the Sumatra earthquake of 2004 and the Tohoku earthquake of 2011 illustrate the issues associated with tsunami warning. Because tsunami waves travel 10 times more slowly than seismic waves, there is enough time after a large suboceanic quake occurs, sometimes many hours, to warn people on distant shorelines of an impending disaster. Warnings broadcast by the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center, based in Hawaii, after the Tohoku earthquake allowed islands such as Hawaii and the western coastlines of the Americas to be evacuated prior to the tsunami arrival (see Figure 13.22). Unfortunately, no such system had been installed in the Indian Ocean, so the 2004 tsunami struck with essentially no warning, killing tens of thousands.

The most difficult situations arise in areas located close to active offshore faults, where tsunamis arrive so quickly that there is no time for a warning. One such place is Papua New Guinea, where in 1998, a tsunami killed as many as 3000 people in coastal villages near the epicenter of the quake that caused it. Such communities could be protected by building barrier walls to block inundation by ocean water, but this type of construction is expensive and has been tried only in Japan with mixed results (Figure 13.31). In these places, the best warning system is a very simple one: if you feel a strong earthquake, move quickly away from the coastal lowlands to higher ground!

374

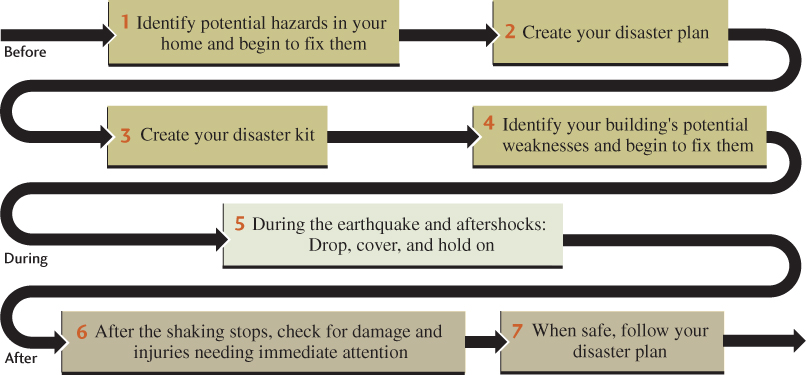

13.2 Seven Steps to Earthquake Safety

Individuals living in seismically active areas need to prepare for earthquakes and know how to respond when one strikes. Here are seven steps to earthquake safety, recommended by the Southern California Earthquake Center, that you can use to protect yourself and your family.

Before an earthquake occurs:

- 1. Identify potential hazards in your home and begin to fix them. As buildings are becoming better designed to withstand seismic shaking, more of the damage and injuries that occur are resulting from falling objects. You should secure items in your home that are heavy enough to cause damage or injury if they fall or valuable enough to be a significant loss if they break.

- 2. Create your disaster plan. With your family or housemates, plan now what you will do before, during, and after an earthquake. The plan should include safe spots you can go to during the shaking, such as under sturdy desks and tables; a safe spot outside your home where you can meet after the shaking stops; and contact phone numbers, including someone outside the area who can be called to relay information in case local communications are disrupted.

- 3. Create your disaster kit. Stock your disaster kit with essential items. Your personal kit should include medications, a first-aid kit, a whistle, sturdy shoes, high-energy snacks, a flashlight with extra batteries, and personal hygiene supplies. Your home kit should include a fire extinguisher, wrenches to turn off gas and water mains, a portable radio, drinking water, food supplies, and extra clothing.

- 4. Identify your building’s potential weaknesses and begin to fix them. Consult a building inspector or contractor to identify potential safety problems. Common problems include inadequate foundations, unbraced cripple walls, weak first stories, unreinforced masonry, and vulnerable pipes.

During an earthquake:

- 5. Drop, cover, and hold on. During an earthquake or severe aftershock, drop to the floor, take cover under a sturdy desk or table, and hold on to it so that it doesn’t move away from you. Wait there until the shaking stops. Stay away from danger zones, such as those near the exterior walls of buildings, near windows, and under architectural façades.

After an earthquake:

- 6. After the shaking stops, check for damage and injuries needing immediate attention. Take care of your own situation first; get to a safe location and remember your disaster plan. If you are trapped, protect your mouth, nose, and eyes from dust; signal for help using a cell phone or whistle or by knocking loudly on a solid part of the building three times every few minutes (rescuers will be listening for such knocks). Check for injuries and treat people needing assistance. Check for fires, gas leaks, damaged electrical systems, and spills. Stay away from damaged structures.

- 7. When safe, follow your disaster plan. Be in communication by turning on your radio and listening for advisories; check your phones, call your out-of-area contact to report your status, and then stay off the phone except for emergencies. Check your food and water supplies and check on your neighbors.

For further information, see Putting Down Roots in Earthquake Country, Southern California Earthquake Center, available online at http://www.earthquakecountry.info/roots/index.php.

375