616

LANDSCAPE DEVELOPMENT

Topography, Elevation, and Relief

Topography, Elevation, and Relief Landforms: Features Sculpted by Erosion and Sedimentation

Landforms: Features Sculpted by Erosion and Sedimentation How Interacting Geosystems Control Landscapes

How Interacting Geosystems Control Landscapes Models of Landscape Development

Models of Landscape Development

617

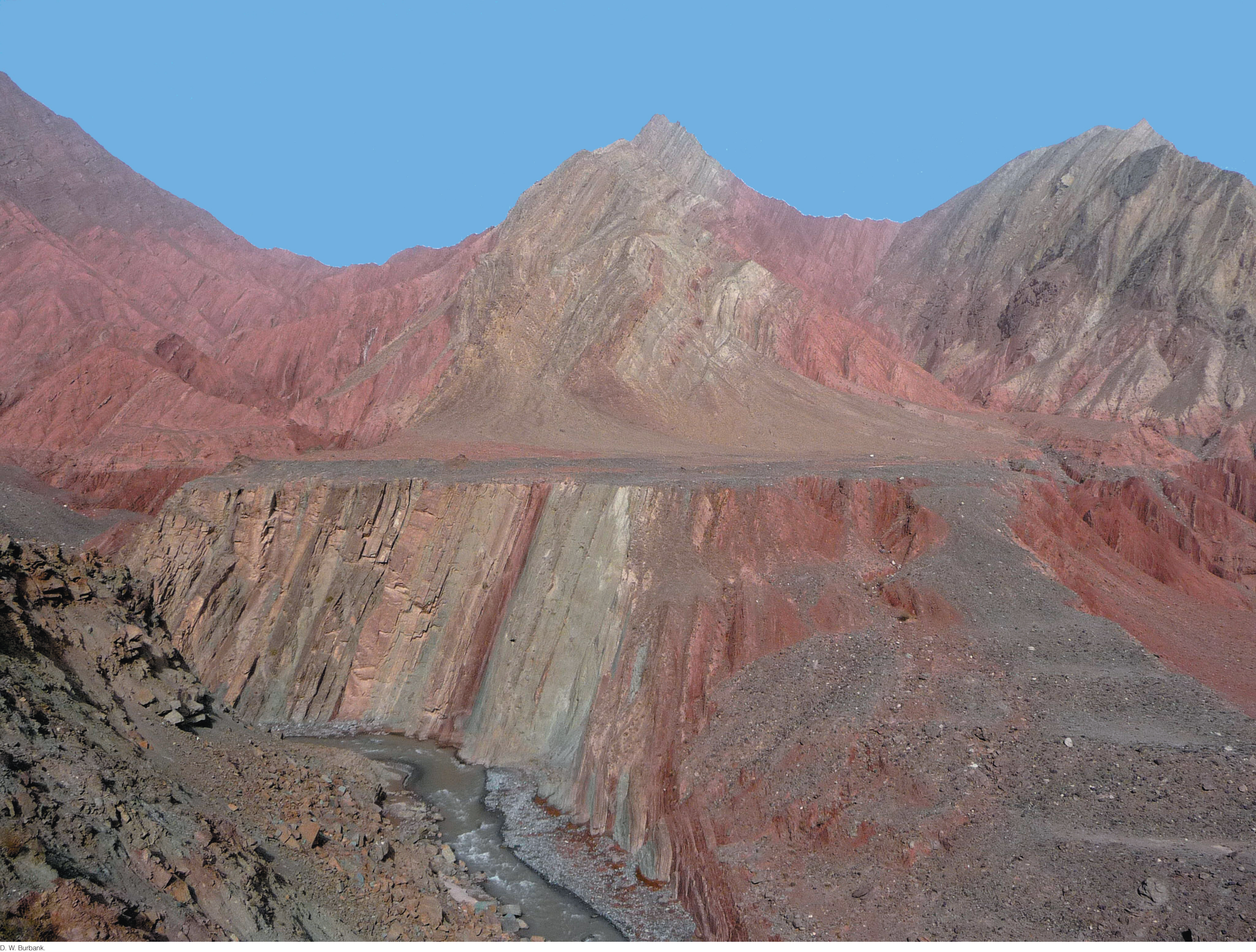

HAVE YOU EVER GAZED out over the horizon and wondered why Earth’s surface has the shape it does, or what forces created that shape? From high snowcapped peaks to broad rolling plains, Earth’s landscapes comprise a diverse array of landforms—large and small, rough and smooth. These landscapes develop through slow changes as the processes of tectonic uplift, weathering, erosion, transportation, and sedimentation combine to sculpt the land surface.

In the past, changes in landscapes were imperceptible on a human time scale, but new technologies now permit us to measure the rates of many of these changes directly. These technologies have revitalized the branch of Earth science known as geomorphology—the study of landscapes and their development. Understanding the slow processes by which landscapes develop helps us not only to manage our land resources, but also to appreciate the linkages between the plate tectonic and climate systems. Geomorphology represents a great challenge to geologists because it requires them to integrate many branches of Earth science.

In the most basic sense, landscapes can be viewed as the result of competition between processes that raise Earth’s surface and those that lower it. Processes driven by the plate tectonic system raise the elevation of Earth’s crust to form mountain ranges and high plateaus. The uplifted rocks are exposed to weathering and erosion—processes driven by the climate system. Thus, the landscape is an expression of the interaction between these two geosystems.

The uplifted areas of Earth’s crust can be narrow or broad, and uplift rates can be fast or slow. Similarly, weathering and erosion may operate over narrow or broad areas, and their intensity can be high or low. Thus, landscapes themselves depend on balance between these processes. Moreover, tectonic and surface processes influence each other. For example, uplift of a mountain range may drive regional (or even global) climate change and thus change weathering rates, which in turn influence the further uplift of the mountains.

618

In this chapter, we will look closely at how the plate tectonic and climate systems—and their component processes, including tectonic uplift, weathering, erosion, mass wasting, and sediment transport and deposition—interact in the dynamic process that sculpts Earth’s landscapes.