Plate Tectonic Forces

Deformation is a general term that encompasses the folding, faulting, shearing, compression, and extension of rock by plate tectonic forces. The types of deformation we see exposed at Earth’s surface are caused mainly by the horizontal movements of the lithospheric plates relative to one another. For this reason, the tectonic forces that deform rocks at plate boundaries are predominantly horizontally directed and depend on the direction of relative plate movement:

Tensional forces, which stretch and pull rock formations apart, dominate at divergent boundaries, where plates move away from each other.

Tensional forces, which stretch and pull rock formations apart, dominate at divergent boundaries, where plates move away from each other. Compressive forces, which squeeze and shorten rock formations, dominate at convergent boundaries, where plates move toward each other.

Compressive forces, which squeeze and shorten rock formations, dominate at convergent boundaries, where plates move toward each other. Shearing forces, which shear two parts of a rock formation in opposite directions, dominate at transform-fault boundaries, where plates slide past each other.

Shearing forces, which shear two parts of a rock formation in opposite directions, dominate at transform-fault boundaries, where plates slide past each other.

If plates were perfectly rigid, the plate boundaries would be sharp lineations, and points on either side of those boundaries would move at the relative plate velocity. This idealization is often a good approximation in the oceans, where rift valleys at mid-ocean ridges, deep-sea trenches, and nearly vertical transform faults form narrow plate boundary zones, often just a few kilometers wide.

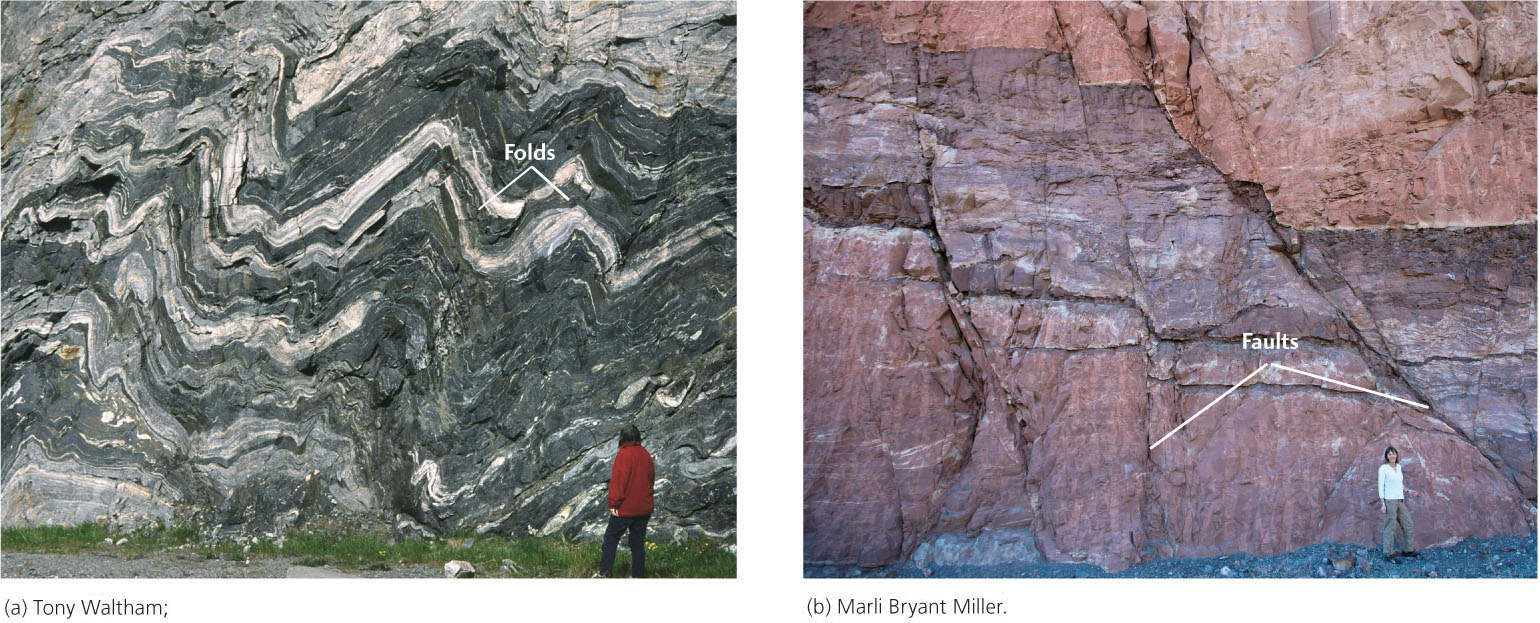

Within continents, however, the deformation caused by plate movements can be “smeared out” across a plate boundary zone hundreds or even thousands of kilometers wide. The continental crust does not behave rigidly within these broad zones, so rocks at the surface are deformed by folding and faulting. Folds in rocks are like folds in clothing. Just as cloth pushed together from opposite sides bunches up in folds, layers of rock slowly compressed by tectonic forces in the crust can be pushed into folds (Figure 7.1a). Tectonic forces can also cause a rock formation to break and slip on both sides of a fracture, forming a fault (Figure 7.1b). When such a break occurs suddenly, the result is an earthquake. Active zones of continental deformation are marked by frequent earthquakes.

Geologic folds and faults can range in size from centimeters to meters (as in Figure 7.1) to tens of kilometers or more. Many mountain ranges are actually a series of large folds and faults that have been weathered and eroded. From the geologic record of deformation laid out on Earth’s surface, geologists can deduce the directions of movement at ancient plate boundaries and reconstruct the tectonic history of the continental crust.