20-11 Neutron stars

On the morning of July 4, 1054, Yang Wei-T’e, the imperial astronomer to the Chinese court, made a startling discovery. Just a few minutes before sunrise, a new and dazzling object ascended above the eastern horizon. This “guest star,” as Yang called it, was far brighter than Venus and more resplendent than any star he had ever seen.

Yang’s records show that the “guest star” was so brilliant that it could easily be seen during broad daylight for the rest of July. Records from Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) also describe this object, and works of art made by the Chacoans in the American Southwest suggest that they may have seen it as well (Figure 20-25). Over the next 21 months, however, the “guest star” faded to invisibility.

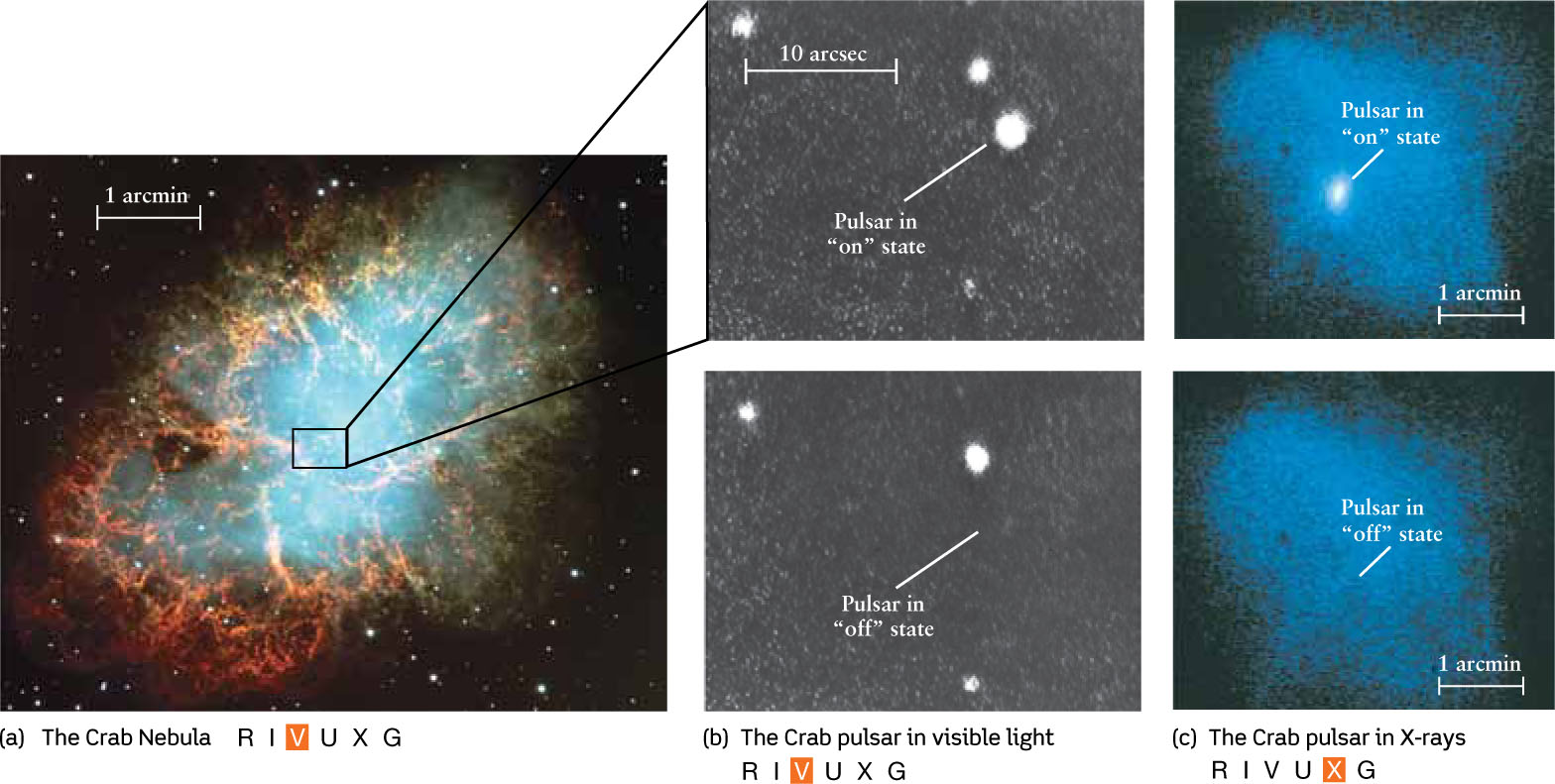

We now know that the “guest star” of 1054 was actually a remarkable stellar transformation: A massive star some 6500 ly away perished in a supernova explosion, leaving behind both a supernova remnant and a bizarre object called a neutron star—an incredibly dense sphere composed primarily of neutrons. (We learned in Section 5-7 that a neutron has about the same mass as a proton, but has no electric charge.) Today, the remnant of this supernova that was seen nearly a thousand years ago is called the Crab Nebula; the neutron star at its center is known as the Crab pulsar for reasons we will see shortly (Figure 20-26a).

We saw in Section 20-6 that under the very high pressures within a core-collapse supernova, a proton and an electron can combine to form a neutron (as well as a neutrino). Far from being a rare transformation, a core-collapse can convert over a solar mass of material into almost pure neutrons. Recall that white dwarfs are supported by degenerate electron pressure, and by a similar effect, neutron stars are supported against further gravitational collapse by degenerate neutron pressure. (Like electrons, neutrons obey the Pauli exclusion principle that we described in Section 19-3.)

Although the possibility for neutron stars to form was proposed in 1934, most scientists politely ignored the idea for years. After all, a neutron star must be a rather weird object. If brought to Earth’s surface, a single teaspoonful of neutron star matter would weigh the same as about 20 million elephants (about 100 million tons)!

Neutron stars can only exist for a narrow range of masses. Supported by degenerate electron pressure, stellar cores below the Chandrasekhar limit of 1.4 M⊙ form white dwarfs. Above the Chandrasekhar limit, a neutron star forms, but the maximum possible neutron star mass is only around 2 to 3 M⊙. Beyond a stellar core mass of 2 to 3 M⊙, gravity overwhelms internal pressure, and a black hole is formed. Keep in mind that these are only the masses of the stellar cores. Stars with total masses between 8 to 25 M⊙ are expected to develop neutron stars, and above 25 M⊙, black holes.

A couple of solar masses is a lot of material, but at extreme densities, these objects are surprisingly small. A 1.4-M⊙ neutron star would have a diameter of only 20 km (12 mi). Thus, a neutron star is like a giant atomic nucleus made only of neutrons, and the size of a city! Its surface gravity would be so strong that its escape speed—the speed an object would need to have in order to escape into space (Section 4-7) would be one-half the speed of light. Even climbing a 1-millimeter “mountain” on a neutron star would require about the same energy as a person on Earth jumping straight to the Moon! These conditions seemed outrageous until the late 1960s, when astronomers discovered pulsating radio sources.

The Discovery of Pulsars

The rapid flashing of radiation from a pulsar gave evidence that white dwarfs are not the only endpoint of stellar evolution

As a young graduate student at Cambridge University, Jocelyn Bell spent many months helping construct an array of radio antennas covering 4½ acres of the English countryside. The instrument was completed by the summer of 1967, and Bell and her colleagues began using it to scrutinize radio emissions from the sky. While searching for something quite different, Bell noticed that the antennas had detected regular pulses of radio noise from one particular location in the sky. These radio pulses were arriving at regular intervals of 1.3373011 seconds—much more rapid than those of any other astronomical object known at that time. Indeed, they were so rapid and regular that the Cambridge team first wondered if they might be signals from an advanced alien civilization.

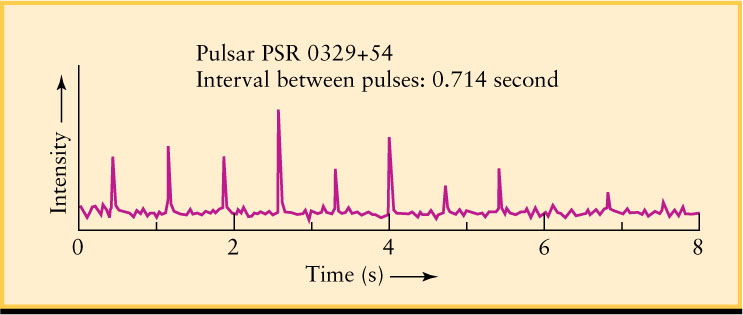

That possibility had to be discarded within a few months after several more of these pulsating radio sources, which came to be called pulsars, were discovered across the sky. In all cases, the periods were extremely regular, ranging from about 0.25 second for the fastest to about 1.5 seconds for the slowest (Figure 20-27). After ruling out other mechanisms to generate such rapid periodic pulses (such as rapidly orbiting binary systems), it appeared that a “hot spot” on a rotating white dwarf might account for pulsars. However, the discovery of a pulsar at the center of the Crab Nebula—called the Crab pulsar (Figure 20-26b)—was about to rule out white dwarfs and fundamentally change astronomy.

At the time of its discovery, the Crab pulsar was the fastest pulsar known to astronomers. Its period is 0.0333 seconds per rotation, which means that it flashes or rotates about 1/0.0333 = 30 times each second. It was immediately apparent to astrophysicists that white dwarfs are too big and bulky to generate 30 signals per second; calculations demonstrated that a white dwarf could not rotate that fast without tearing itself apart! Hence, the Crab pulsar indicated that pulsars had to be much smaller and more compact than a white dwarf. We now understand that pulsars arise from rapidly rotating neutron stars, which were created in supernova explosions. This was truly remarkable, because most astronomers in the mid-1960s thought that all stellar corpses are white dwarfs.

The neutron star model of pulsars had to pass several stringent tests to be accepted by astronomers

Because neutron stars are very small, they should also rotate rapidly. A typical star, such as our Sun, takes nearly a full month to rotate once about its axis. But just as a spinning ice skater speeds up when she pulls in her arms, a collapsing star also speeds up as its size shrinks. (We introduced this principle, called the conservation of angular momentum, in Section 8-4; see Figure 8-7.) If our Sun were compressed to the size of a neutron star, it would spin about 1000 times per second! Because neutron stars are so small and dense, they can spin this rapidly without flying apart.

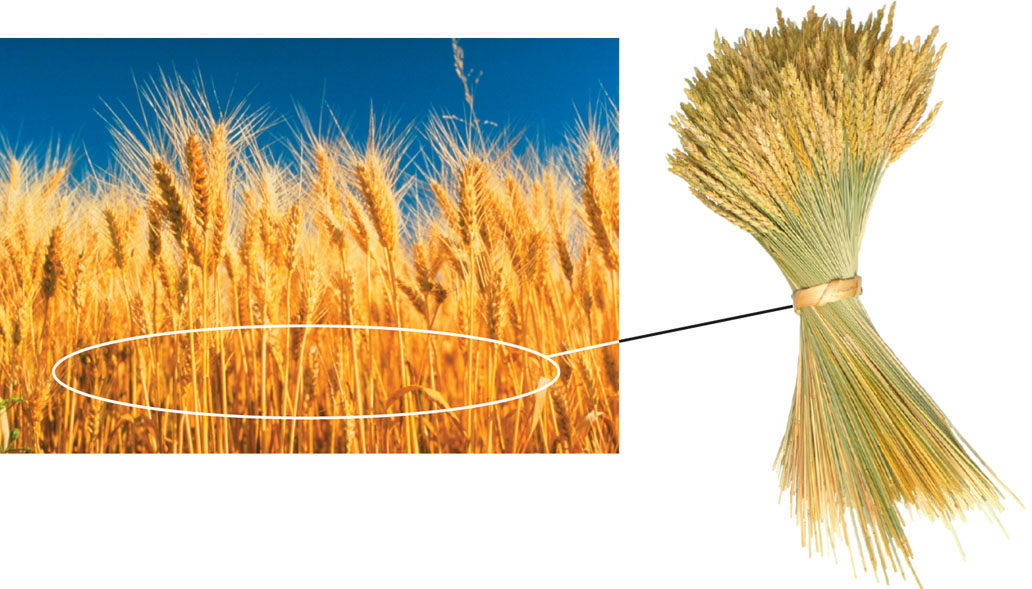

Analogy for How Magnetic Field Strengths Increase When growing, these wheat stalks cover a much larger area than when they are harvested and bound together. A star’s magnetic field behaves similarly. The collapsing star carries the field inward, thereby increasing its strength.

The small size of neutron stars also leads to intense magnetic fields. The magnetic field of a main-sequence star is spread out over billions of square kilometers of the star’s surface. However, if such a star collapses down to a neutron star, its surface area shrinks by a factor of about 1010. The magnetic field, which weaves through and is connected to the star’s ionized gases (see Section 16-9), becomes concentrated over a smaller area than before the collapse and increases by a factor of 1010 (Figure 20-28)

How can astronomers determine the strength of a neutron star’s magnetic field? Certain spectral lines can be split apart—after initially appearing as a single line—and the greater the magnetic field, the farther apart the lines move. This method reveals that magnetic fields on neutron stars are over a million times stronger than the strongest fields produced in labs on Earth.

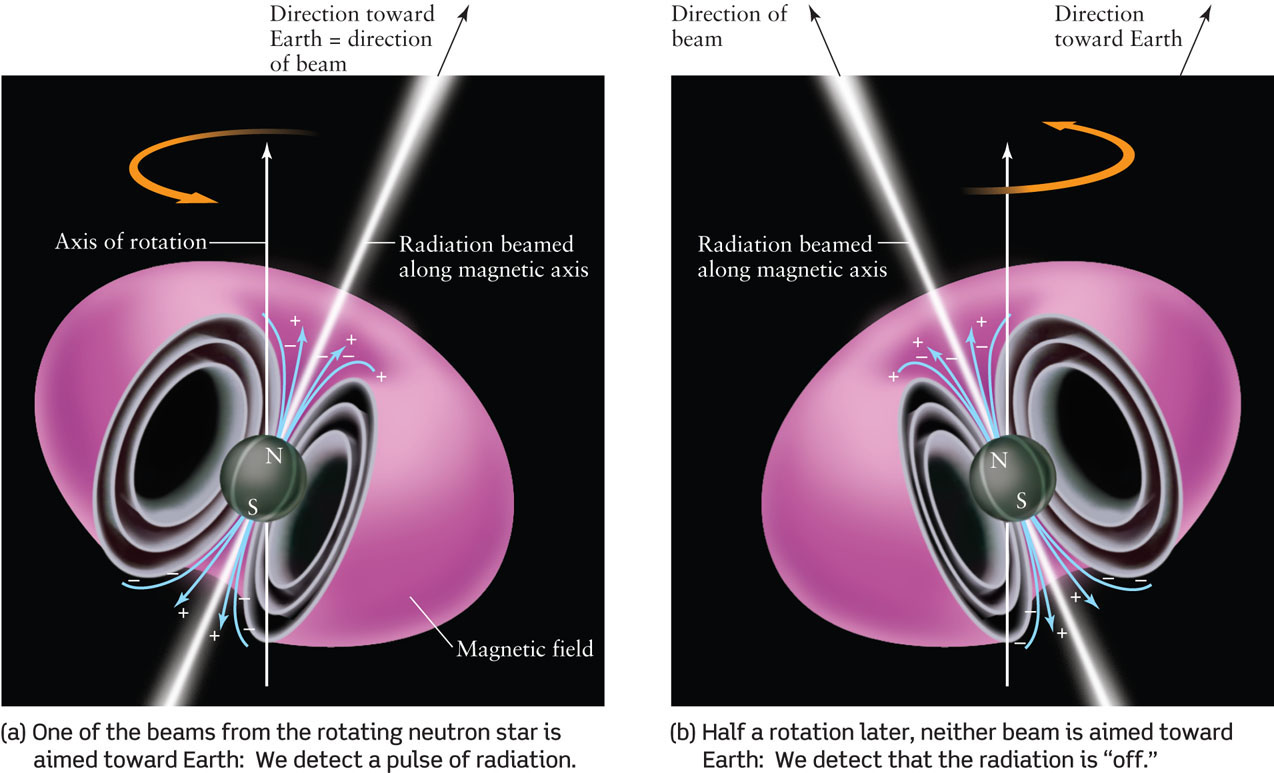

The magnetic field of a neutron star makes it possible for the star to radiate pulses of energy toward our telescopes. As a neutron star rotates, the magnetic axis of a neutron star—the imaginary line passing through the north and south magnetic poles—is likely to be inclined at an angle to the rotation axis (Figure 20-29). After all, there is no fundamental reason for these two axes to coincide. (Indeed, these two axes do not coincide for any of the planets of our solar system.) Furthermore, nearby electrically charged particles are accelerated by the magnetic fields, and this motion produces electromagnetic radiation. The result is that two narrow beams of radiation pour out of the neutron star’s north and south magnetic polar regions. While pulsars were originally discovered at radio wavelengths, some also pulse in visible light and X-rays (Figure 20-26b,c). Note that a neutron star is not a star in the usual sense: it isn’t powered by nuclear reactions.

ANALOGY

A rotating, magnetized neutron star is somewhat like a lighthouse beacon. As the star rotates, the beams of radiation sweep around the sky. If at some point during the rotation one of those beams happens to point toward Earth, as shown in Figure 20-29a, we will detect a brief flash as the beam sweeps over us. At other points during the rotation, the beam will be pointed away from Earth, and the radiation from the neutron star will appear to have turned off (Figure 20-29b). Hence, a radio telescope will detect regular pulses of radiation, with one pulse being received for each rotation of the neutron star.

CAUTION!

The name pulsar may lead you to think that the source of radio waves is actually pulsing. But in the model just described, this is not the case at all. Instead, beams of radiation are emitted continuously from the magnetic poles of the neutron star. The pulsing that astronomers detect here on Earth is simply a result of the rapid rotation of the neutron star, which brings one of the beams periodically into our line of sight, as Figure 20-29 shows. In this sense, the analogy between a pulsar and a lighthouse beacon is a very close one.

CONCEPT CHECK 20-17

What prevents a neutron star from collapsing under its own tremendous gravitational attraction?

Just as a white dwarf is held up by degenerate electron pressure, a neutron star is held up by degenerate neutron pressure.

CONCEPT CHECK 20-18

How can a rotating neutron star lead to radio pulses?

By shrinking during formation, neutron stars spin rapidly and have very large magnetic fields. Charged particles in these magnetic fields emit the light (often radio waves) observed at Earth. The light arrives in pulses the way a lighthouse beacon repeatedly sweeps by an observer.