23-1 When galaxies were first discovered, it was not clear that they lie far beyond the Milky Way

As early as 1755, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant suggested that vast collections of stars lie outside the confines of the Milky Way. Less than a century later, an Irish astronomer observed the structure of some of the “island universes” that Kant proposed.

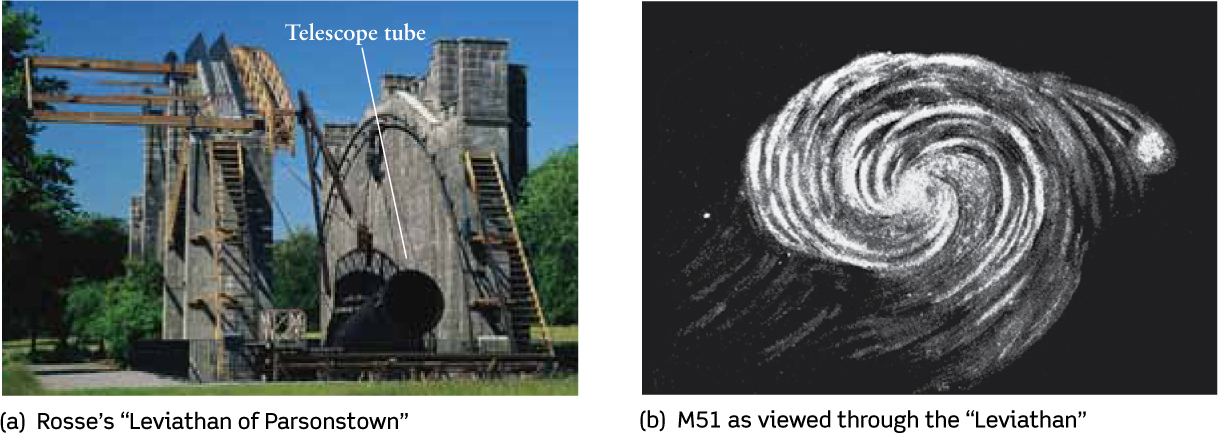

William Parsons, the third Earl of Rosse, was a wealthy amateur astronomer who used his fortune to build immense telescopes. His largest telescope, completed in February 1845, had an objective mirror 1.8 meters (6 feet) in diameter (Figure 23-1). The mirror was mounted at one end of a 60-foot tube controlled by cables, straps, pulleys, and cranes (Figure 23-1a). For many years, this triumph of nineteenth-century engineering was the largest telescope in the world.

A Pioneering View of Another Galaxy (a) Built in 1845, this structure housed the largest telescope of its day. The telescope itself (the black cylinder pointing at a 45° angle above the horizontal) was restored to its original state during 1996–1998. (b) Using his telescope, Lord Rosse made this sketch of spiral structure in M51. This galaxy, whose angular size is 8 × 11 arcminutes (about a third the angular size of the full moon), is today called the Whirlpool Galaxy because of its distinctive appearance.

As late as the 1920s it was unclear whether spiral nebulae were very remote “island universes” or simply nearby parts of our Galaxy

With this new telescope, Rosse examined many of the nebulae that had been discovered and cataloged by William Herschel. He observed that some of these nebulae have a distinct spiral structure. One of the best examples is M51, also called NGC 5194. (The “M” designations of galaxies and nebulae come from a catalog compiled by the French astronomer Charles Messier between 1758 and 1782. The “NGC” designations come from the much more extensive “New General Catalogue” of galaxies and nebulae published in 1888 by J. L. E. Dreyer, a Danish astronomer who lived and worked in Ireland.)

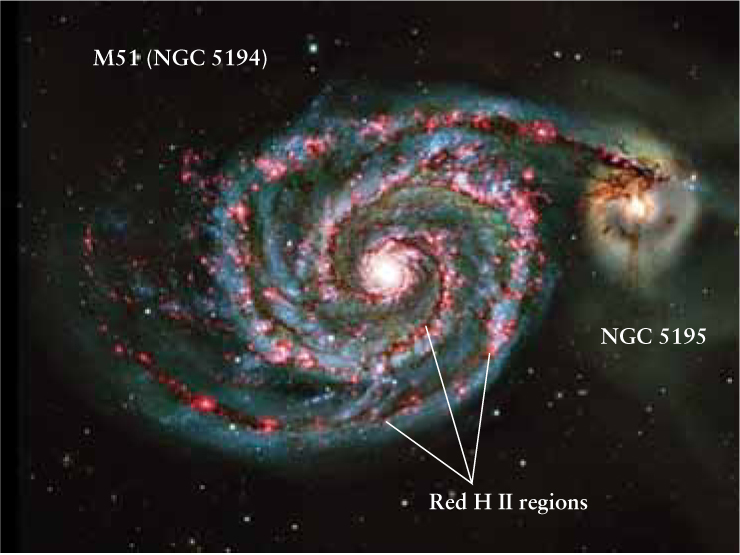

A Modern View of the Spiral Galaxy M51 This galaxy, also called NGC 5194, has spiral arms that are outlined by glowing H II regions. These regions reveal the sites of star formation (see Section 18-2). One spiral arm extends toward the companion galaxy NGC 5195.

Lacking photographic equipment, Lord Rosse had to make drawings of what he saw. Figure 23-1b shows a drawing he made of M51, which compares favorably with modern photographs, as shown in Figure 23-2. Views such as this inspired Lord Rosse to echo Kant’s proposal that such nebulae are actually “island universes.”

Many astronomers of the nineteenth century disagreed with this notion of island universes. A considerable number of nebulae are in fact scattered throughout the Milky Way. (Figure 18-2 and Figure 18-4 show some examples.) The safest assumption was that “spiral nebulae,” even though they are very different in shape from other sorts of nebulae, could also be components of our Galaxy.

The astronomical community became increasingly divided over the nature of the spiral nebulae. In April 1920, two opposing ideas were presented before the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. On one side was Harlow Shapley from the Mount Wilson Observatory, renowned for his recent determination of the size of the Milky Way Galaxy (see Section 22-1). Shapley thought the spiral nebulae were relatively small, nearby objects scattered around our Galaxy like the globular clusters he had studied. Opposing Shapley was Heber D. Curtis of the University of California’s Lick Observatory. Curtis championed the island universe theory, arguing that each of these spiral nebulae is a rotating system of stars much like our own Galaxy.

The Shapley-Curtis “debate” generated much heat but little light. Nothing was decided, because no one could present conclusive evidence to demonstrate exactly how far away the spiral nebulae are. Astronomy desperately needed a definitive determination of the distance to a spiral nebula. Such a measurement became the first great achievement of a young man who studied astronomy at the Yerkes Observatory, near Chicago. His name was Edwin Hubble.

CONCEPT CHECK 23-1

If you were observing one of the “spiral nebulae” and determined that it was closer than some of the stars of our Galaxy, would you be providing evidence in support of Shapley’s argument or Curtis’s argument?

If spiral nebulae are closer than some of the stars of our Galaxy, then the evidence presented supports Shapley’s argument that spiral nebulae are within our Galaxy and are not themselves large galaxies very far away.