2-3 The appearance of the sky changes during the course of the night and from one night to the next

Go outdoors soon after dark, find a spot away from bright lights, and note the patterns of stars in the sky. Do the same a few hours later. You will find that the entire pattern of stars (as well as the Moon, if it is visible) has shifted its position. New constellations will have risen above the eastern horizon, and some will have disappeared below the western horizon. If you look again before dawn, you will see that the stars that were just rising in the east when the night began are now low in the western sky. This daily motion, or diurnal motion, of the stars is apparent in time-exposure photographs (see the photograph that opens this chapter).

By understanding the motions of Earth through space, we can understand why the Sun and stars appear to move in the sky

If you repeat your observations on the following night, you will find that the motions of the sky are almost but not quite the same. The same constellations rise in the east and set in the west, but a few minutes earlier than on the previous night. If you look again after a month, the constellations visible at a given time of night (say, midnight) will be noticeably different, and after six months you will see an almost totally different set of constellations. Only after a year has passed will the night sky have the same appearance as when you began.

Why does the sky go through diurnal motion? Why do the constellations slowly shift from one night to the next? As we will see, the answer to the first question is that Earth rotates once a day around an axis from the north pole to the south pole, while the answer to the second question is that Earth also revolves once a year around the Sun.

Diurnal Motion and Earth’s Rotation

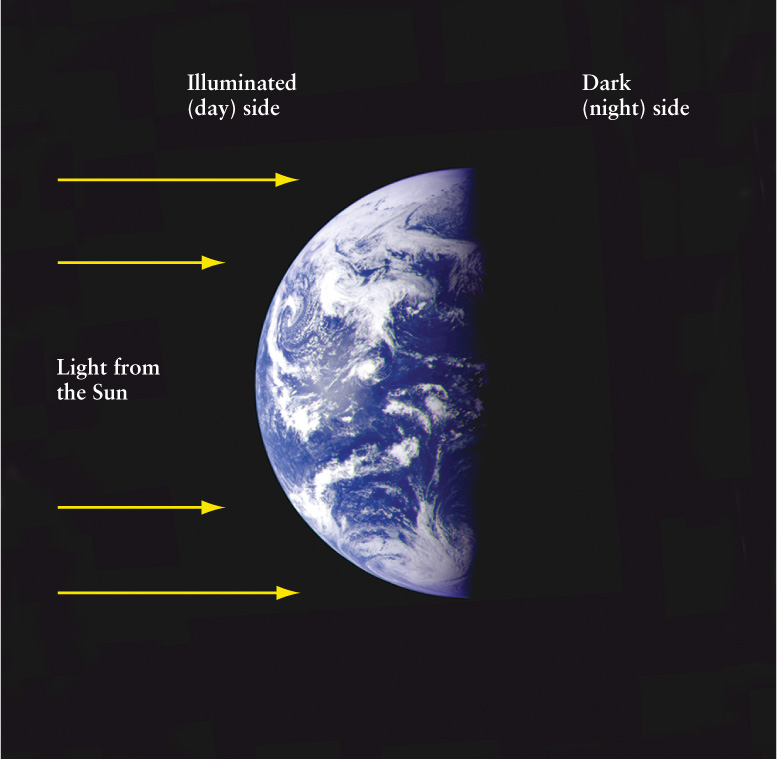

Day and Night on Earth At any moment, half of Earth is illuminated by the Sun. As Earth rotates from west to east, your location moves from the dark (night) hemisphere into the illuminated (day) hemisphere and back again. This image was recorded in 1992 by the Galileo spacecraft as it was en route to Jupiter.

To understand diurnal motion, note that at any given moment it is daytime on the half of Earth illuminated by the Sun and nighttime on the other half (Figure 2-3). Earth rotates from west to east, making one complete rotation every 24 hours, which is why there is a daily cycle of day and night. Because of this rotation, stars appear to us to rise in the east and set in the west, as do the Sun and Moon.

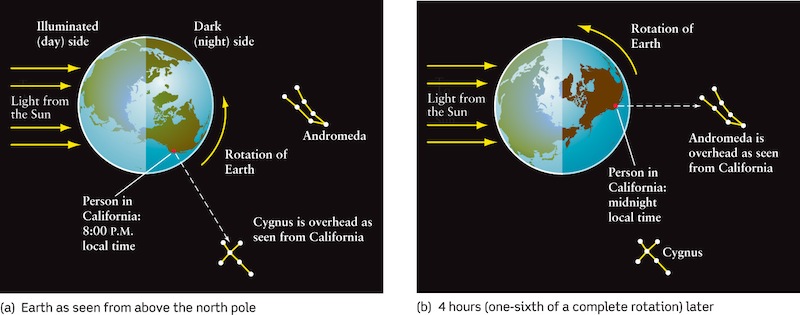

Figure 2-4 helps to further explain diurnal motion. It shows two views of Earth as seen from a point above the north pole. At the instant shown in Figure 2-4a, it is day in Asia but night in most of North America and Europe. Figure 2-4b shows Earth four hours later. Four hours is one-sixth of a complete 24-hour day, so Earth has made one-sixth of a rotation between Figure 2-4a and Figure 2-4b. Europe is now in the illuminated half of Earth (the Sun has risen in Europe), while Alaska has moved from the illuminated to the dark half of Earth (the Sun has set in Alaska). For a person in California, in Figure 2-4a the time is 8:00 p.m. and the constellation Cygnus (the Swan) is directly overhead. Four hours later, the constellation over California is Andromeda (named for a mythological princess). Because Earth rotates from west to east, it appears to us on Earth that the entire sky rotates around us in the opposite direction, from east to west.

Why Diurnal Motion Happens The diurnal (daily) motion of the stars, the Sun, and the Moon is a consequence of Earth’s rotation. (a) This drawing shows Earth from a vantage point above the north pole. In this drawing, for a person in California the local time is 8:00 p.m. and the constellation Cygnus is directly overhead. (b) Four hours later, Earth has made one-sixth of a complete rotation to the east. As seen from Earth, the entire sky appears to have rotated to the west by one-sixth of a complete rotation. It is now midnight in California, and the constellation directly over California is Andromeda.

Why Diurnal Motion Happens The diurnal (daily) motion of the stars, the Sun, and the Moon is a consequence of Earth’s rotation. (a) This drawing shows Earth from a vantage point above the north pole. In this drawing, for a person in California the local time is 8:00 p.m. and the constellation Cygnus is directly overhead. (b) Four hours later, Earth has made one-sixth of a complete rotation to the east. As seen from Earth, the entire sky appears to have rotated to the west by one-sixth of a complete rotation. It is now midnight in California, and the constellation directly over California is Andromeda.

CONCEPT CHECK 2-2

People in which of the following cities in North America experience sunrise first: New York, San Francisco, Chicago, or Denver? Explain in terms of Earth’s rotation.

Earth rotates from west to east. As locations on Earth rotate from the dark, nighttime side of the planet into the bright, daytime side of the planet, the easternmost cities experience sunrise first. New York is the farthest east of the cities listed, so the sun rises there first.

CALCULATION CHECK 2-1

If the constellation of Cygnus rises along the eastern horizon at sunset, at what time will it be highest above the southern horizon?

Earth rotates once in 24 hours, so when the stars of Cygnus rise in the east at sunset, they take about 12 hours to go from one side of the sky to the other. As a result, it takes about one half of that time, or 6 hours, for stars of Cygnus to move halfway across the sky. Thus, Cygnus will be highest in the sky around midnight.

Yearly Motion and Earth’s Orbit

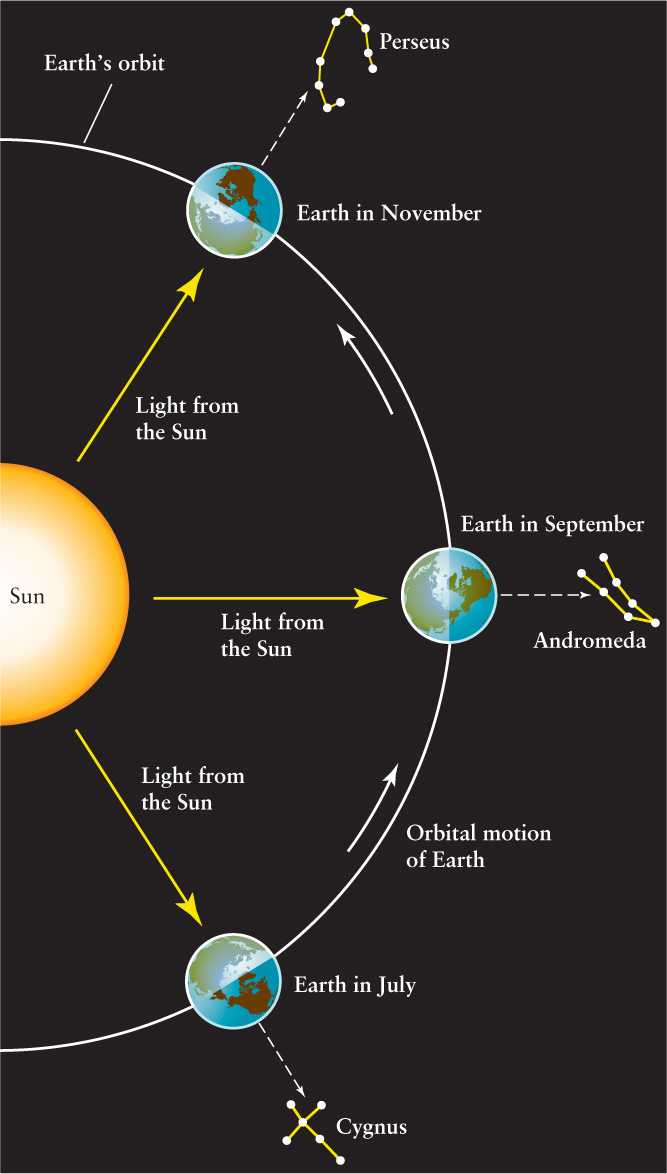

We described earlier that in addition to the diurnal motion of the sky, the constellations visible in the night sky also change slowly over the course of a year. This happens because Earth orbits, or revolves around, the Sun (Figure 2-5). Over the course of a year, Earth makes one complete orbit, and the darkened, nighttime side of Earth gradually turns toward different parts of the heavens. For example, as seen from the northern hemisphere, at midnight in late July the constellation Cygnus is close to overhead; at midnight in late September the constellation Andromeda is close to overhead; and at midnight in late November the constellation Perseus (commemorating a mythological hero) is close to overhead. If you follow a particular star on successive evenings, you will find that it rises approximately 4 minutes earlier each night, or 2 hours earlier each month.

CONCEPT CHECK 2-3

If Earth suddenly rotated on its axis 3 times faster than it does now, then how many times would the Sun rise and set each year?

The Sun would still only rise and set once each day (since that defines what a day is), but each year would have 3 times as many days (365 × 3 = 1095 days each year), and each day would be 3 times shorter.

Constellations and the Night Sky

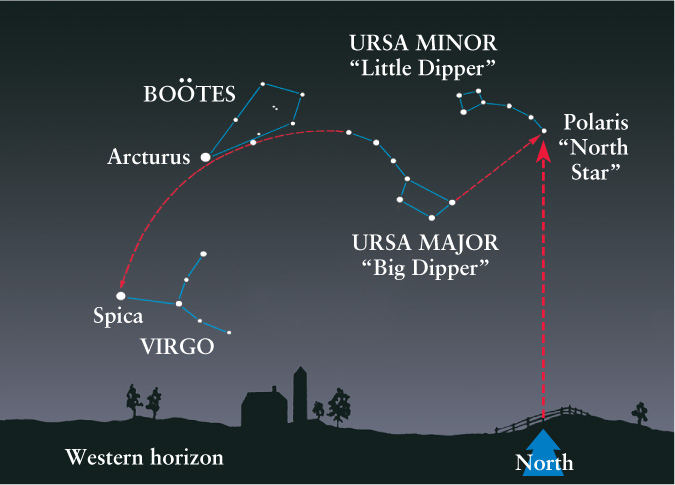

Constellations can help you find your way around the sky. For example, if you live in the northern hemisphere, you can use the Big Dipper in Ursa Major to find the north direction by drawing a straight line through the two stars at the front of the Big Dipper’s bowl (Figure 2-6). The first moderately bright star you come to is Polaris, also called the North Star because it is located almost directly over Earth’s north pole. If you draw a line from Polaris straight down to the horizon, you will find the north direction.

As Figure 2-6 shows, by following the handle of the Big Dipper you can locate the bright reddish star Arcturus in Boötes (the Shepherd) and the prominent bluish star Spica in Virgo (the Virgin). The saying “Follow the arc to Arcturus and speed to Spica” may help you remember these stars, which are conspicuous in the evening sky during the spring and summer.

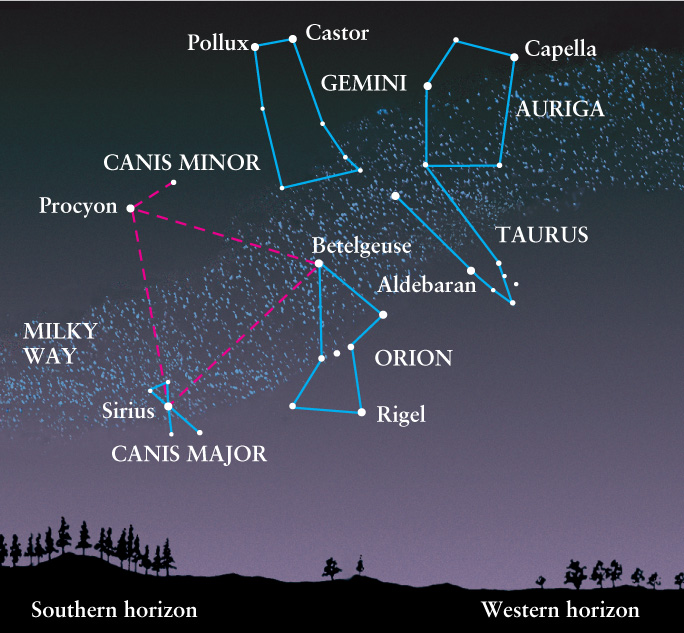

During winter in the northern hemisphere, you can see some of the brightest stars in the sky. Many of them are in the vicinity of the “winter triangle” (Figure 2-7), which connects bright stars in the constellations of Orion (the Hunter), Canis Major (the Large Dog), and Canis Minor (the Small Dog).

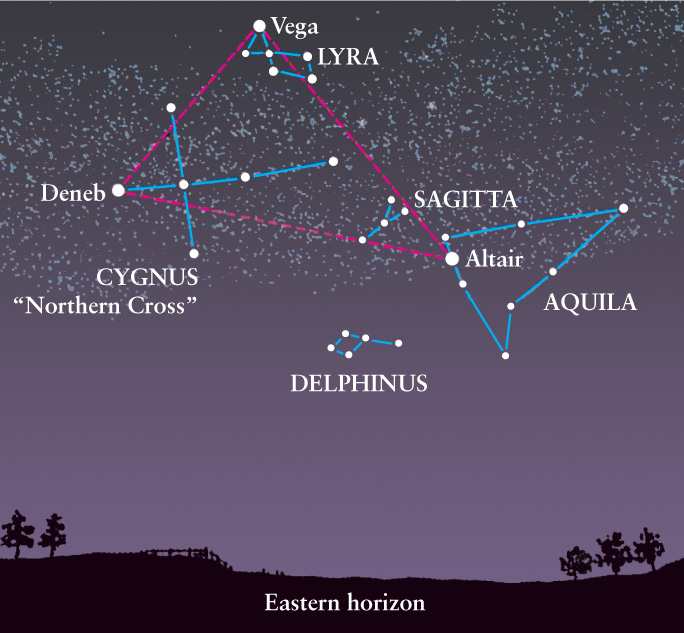

A similar feature, the “summer triangle,” graces the summer sky in the northern hemisphere. This triangle connects the brightest stars in Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), and Aquila (the Eagle) (Figure 2-8). A conspicuous portion of the Milky Way forms a beautiful background for these constellations, which are nearly overhead during the middle of summer at midnight.

A wonderful tool to help you find your way around the night sky is the planetarium program Starry Night™, which is on the CD-ROM that accompanies certain print copies of this book. (You can also obtain Starry Night™ separately.) In addition, at the end of this book you will find a set of selected star charts for the evening hours of all 12 months of the year. You may find stargazing an enjoyable experience, and Starry Night™ and the star charts will help you identify many well-known constellations.

Note that all the star charts in this section and at the end of this book are drawn for an observer in the northern hemisphere. If you live in the southern hemisphere, you can see constellations that are not visible from the northern hemisphere, and vice versa. In the next section we will see why this is so.