2-6 The Moon helps to cause precession, a slow, conical motion of Earth’s axis of rotation

Precession causes the apparent positions of the stars to slowly change over the centuries

The Moon is by far the brightest and most obvious naked-eye object in the nighttime sky. Like the Sun, the Moon slowly changes its position relative to the background stars; unlike the Sun, the Moon makes a complete trip around the celestial sphere in only about 4 weeks, or about a month. (The word “month” comes from the same Old English root as the word “moon.”) Ancient astronomers realized that this motion occurs because the Moon orbits Earth in roughly 4 weeks. In 1 hour, the Moon moves on the celestial sphere by about ½°, or roughly its own angular size.

The Moon’s path on the celestial sphere is never far from the Sun’s path (that is, the ecliptic). This is because the plane of the Moon’s orbit around Earth is inclined only slightly from the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun (the ecliptic plane shown in Figure 2-14a). The Moon’s path varies somewhat from one month to the next, but always remains within a band called the zodiac that extends about 8° on either side of the ecliptic. Twelve famous constellations—Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpius, Sagittarius, Capricornus, Aquarius, and Pisces—lie along the zodiac. The Moon is generally found in one of these 12 constellations. (Thanks to a redrawing of constellation boundaries in the mid-twentieth century, the zodiac actually passes through a thirteenth constellation—Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer—between Scorpius and Sagittarius.) As it moves along its orbit, the Moon appears north of the celestial equator for about two weeks and then south of the celestial equator for about the next two weeks. We will learn more about the Moon’s motion, as well as why the Moon goes through phases, in Chapter 3.

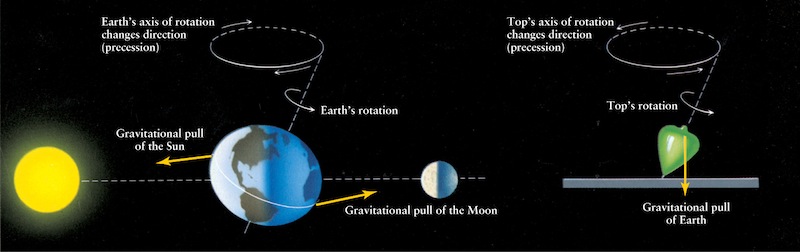

The Moon not only moves around Earth but, in concert with the Sun, also causes a slow change in Earth’s rotation. This is because both the Sun and the Moon exert a gravitational pull on Earth. We will learn much more about gravity in Chapter 4; for now, all we need is the idea that gravity is a universal attraction of matter for other matter.

The gravitational pull of the Sun and the Moon affects Earth’s rotation because Earth is slightly fatter across the equator than it is from pole to pole: Its equatorial diameter is 43 kilometers (27 miles) larger than the diameter measured from pole to pole. Earth is therefore said to have an “equatorial bulge.” Because of the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun on this bulge, the orientation of Earth’s axis of rotation gradually changes, producing a motion called precession. Although the details are beyond the scope of this book, the combined actions of gravity and rotation cause Earth’s axis to trace out a circle in the sky (Figure 2-19). As the axis precesses, it remains tilted about 23½° to the perpendicular.

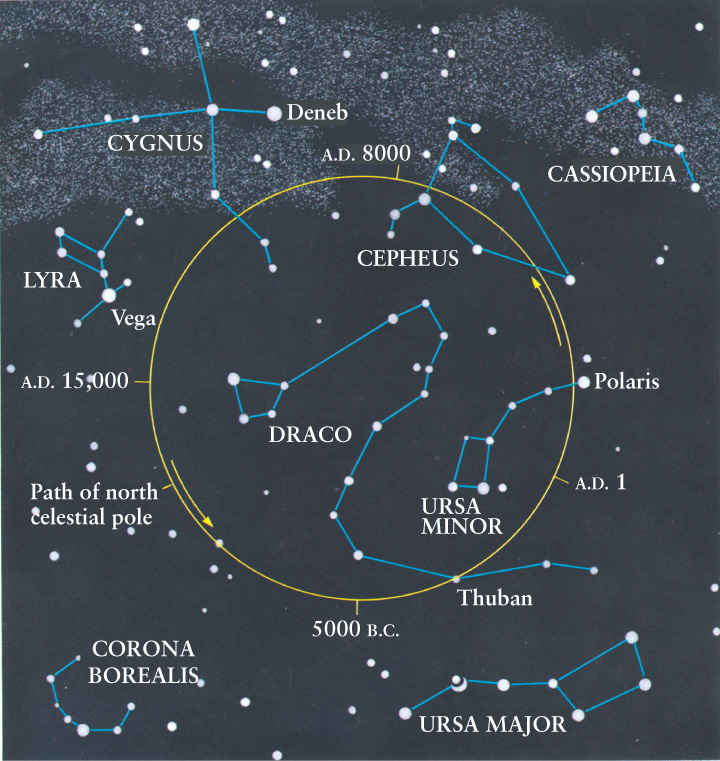

As Earth’s axis of rotation slowly changes its orientation, the north and south celestial poles—which are the projections of that axis onto the celestial sphere—change their positions relative to the stars. At present, the north celestial pole lies within 1° of the star Polaris, which is why Polaris is the North Star. But 5000 years ago, the north celestial pole was closest to the star Thuban in the constellation of Draco (the Dragon). Thus, that star and not Polaris was the North Star. And 12,000 years from now, the North Star will be the bright star Vega in Lyra (the Harp). It takes 26,000 years for the north celestial pole to complete one full precessional circle around the sky (Figure 2-20). The south celestial pole executes a similar circle in the southern sky.

Precession also causes Earth’s equatorial plane to change its orientation. Because this plane defines the location of the celestial equator in the sky, the celestial equator precesses as well. The intersections of the celestial equator and the ecliptic define the equinoxes (see Figure 2-15), so these key locations in the sky also shift slowly from year to year. For this reason, the precession of Earth is also called the precession of the equinoxes. The first person to detect the precession of the equinoxes, in the second century b.c.e., was the Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who compared his own observations with those of Babylonian astronomers three centuries earlier. Today, the vernal equinox is located in the constellation Pisces (the Fishes). Two thousand years ago, it was in Aries (the Ram). Around the year 2600 c.e, the vernal equinox will move into Aquarius (the Water Bearer).

CAUTION!

Astrological terms like the “Age of Aquarius” involve boundaries in the sky that are not recognized by astronomers and are generally not even related to the positions of the constellations. For example, most astrologers would call a person born on March 21, 1988, an “Aries” because the Sun was supposedly in the direction of that constellation on March 21. But due to precession, the Sun was actually in the constellation Pisces on that date! Indeed, astrology is not a science at all, but merely a collection of superstitions and hokum. Its practitioners use some of the terminology of astronomy but reject the logical thinking that is at the heart of science. James Randi has more to say about astrology and other pseudosciences in his essay “Why Astrology Is Not Science” at the end of this chapter.

The astronomer’s system of locating heavenly bodies by their right ascension and declination, discussed in Box 2-1, is tied to the positions of the celestial equator and the vernal equinox. Because of precession, these positions are changing, and thus the coordinates of stars in the sky are also constantly changing. These changes are very small and gradual, but they add up over the years. To cope with this difficulty, astronomers always make note of the date (called the epoch) for which a particular set of coordinates is precisely correct. Consequently, star catalogs and star charts are periodically updated. Most current catalogs and star charts are prepared for the epoch 2000. The coordinates in these reference books, which are precise for January 1, 2000, will require very little correction over the next few decades.