The Missouri Compromise

Printed Page 286

The politics of race produced the most divisive issue during Monroe’s term. In February 1819, Missouri — so recently the territory of the powerful Osage Indians — applied for statehood. Since 1815, four other states (Indiana, Mississippi, Illinois, and Alabama) had joined the Union, following the blueprint laid out by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. But Missouri posed a problem. Although much of its area was on the same latitude as the free state of Illinois, its territorial population included ten thousand slaves brought there by southern planters.

The problem led a New York congressman, James Tallmadge Jr., to propose two amendments to the statehood bill. The first stipulated that slaves born in Missouri after statehood would be free at age twenty-five, and the second declared that no new slaves could be imported into the state. Tallmadge’s model was New York’s gradual emancipation law of 1799 (see "Equality and Slavery" in chapter 8). It did not strip slave owners of their current property, and it allowed them full use of the labor of newborn slaves well into their prime productive years. Still, southern congressmen objected because in the long run the amendments would make Missouri a free state, presumably no longer allied with southern economic and political interests. Just as southern economic power rested on slave labor, southern political power drew extra strength from the slave population because of the three-fifths rule. In 1820, the South owed seventeen of its seats in the House of Representatives to its slave population.

Tallmadge’s amendments passed in the House by a close and sharply sectional vote of North against South. The ferocious debate led a Georgia representative to observe that the question had started “a fire which all the waters of the ocean could not extinguish. It can be extinguished only in blood.” The Senate, with an even number of slave and free states, voted down the amendments, and Missouri statehood was postponed until the next congressional term.

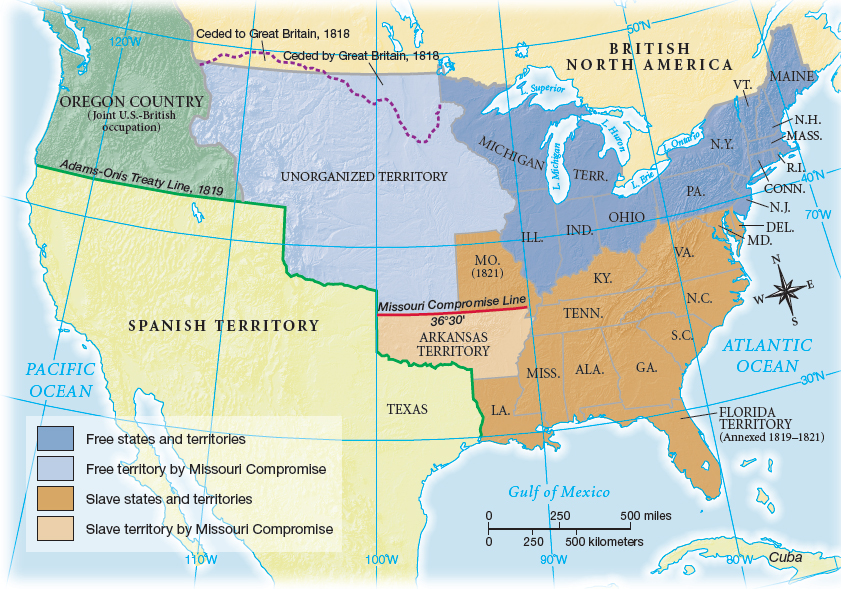

In 1820, a compromise emerged. Maine, once part of Massachusetts, applied for statehood as a free state, balancing against Missouri as a slave state. The Senate further agreed that the southern boundary of Missouri — latitude 36°30’ — extended west, would become the permanent line dividing slave from free states, guaranteeing the North a large area where slavery was banned (Map 10.4). The House also approved the Missouri Compromise, thanks to expert deal brokering by Kentucky’s Henry Clay. The whole package passed because seventeen northern congressmen decided that minimizing sectional conflict was the best course and voted with the South.

1820 congressional compromise engineered by Henry Clay that paired Missouri’s entrance into the Union as a slave state with Maine’s entrance as a free state. The compromise also established Missouri’s southern border as the permanent line dividing slave from free states.

1820 congressional compromise engineered by Henry Clay that paired Missouri’s entrance into the Union as a slave state with Maine’s entrance as a free state. The compromise also established Missouri’s southern border as the permanent line dividing slave from free states.

President Monroe and former president Jefferson at first worried that the Missouri crisis would reinvigorate the Federalist Party as the party of the North. But even ex-Federalists agreed that the split between free and slave states was too dangerous a fault line to be permitted to become a shaper of national politics. When new parties did develop in the 1830s, they took pains to bridge geography, each party developing a presence in both the North and the South. Monroe and Jefferson also worried about the future of slavery. Both understood slavery to be deeply problematic, but, as Jefferson said, “We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”