The Second Great Awakening

Printed Page 315

A newly invigorated version of Protestantism gained momentum in the 1820s and 1830s as the economy reshaped gender and age relations. The earliest manifestations of this fervent piety, which historians call the Second Great Awakening, appeared in 1801 in Kentucky, when a crowd of ten thousand people camped out on a hillside at Cane Ridge for a revival meeting that lasted several weeks. By the 1810s and 1820s, “camp meetings” had spread to the Atlantic seaboard states, accelerating and intensifying the emotional impact of the revival.

Unprecedented religious revival in the 1820s and 1830s that promised access to salvation. The Second Great Awakening proved to be a major impetus for reform movements of the era, inspiring efforts to combat drinking, sexual sin, and slavery.

Unprecedented religious revival in the 1820s and 1830s that promised access to salvation. The Second Great Awakening proved to be a major impetus for reform movements of the era, inspiring efforts to combat drinking, sexual sin, and slavery.

The gatherings attracted women and men hungry for a more immediate access to spiritual peace, one not requiring years of soul-searching. One eyewitness reported that “some of the people were singing, others praying, some crying for mercy. … At one time I saw at least five hundred swept down in a moment as if a battery of a thousand guns had been opened upon them, and then immediately followed shrieks and shouts that rent the very heavens.”

From 1800 to 1820, church membership doubled in the United States, much of it among the evangelical groups. Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians formed the core of the new movement, which attracted women more than men; wives and mothers typically recruited husbands and sons to join them.

A central leader of the Second Great Awakening was a lawyer turned minister named Charles Grandison Finney. Finney lived in western New York, where the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 fundamentally altered the social and economic landscape overnight. Growth and prosperity came with other, less admirable side effects, such as prostitution, drinking, and gaming. Finney saw New York canal towns as ripe for evangelical awakening. In Rochester, he sustained a six-month revival through the winter of 1830–31, generating thousands of converts.

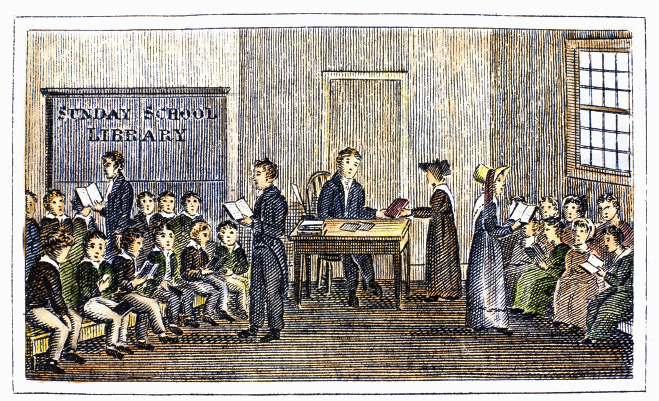

Finney’s message, directed primarily at the business classes, argued for a public-spirited outreach to the less-than-perfect to foster their salvation. Evangelicals promoted Sunday schools to bring piety to children; they battled to honor the Sabbath by ending mail delivery, stopping public transport, and closing shops on Sundays. Many women formed missionary societies that distributed millions of Bibles and religious tracts. Through such avenues, evangelical religion offered women expanded spheres of influence. Finney adopted the tactics of Jacksonian-era politicians — publicity, argumentation, rallies, and speeches — to sell his cause. His object, he said, was to get Americans to “vote in the Lord Jesus Christ as the governor of the Universe.”