Why did the United States go to war with Mexico?

Printed Page 342

CHRONOLOGY

1841

- – Vice President John Tyler becomes president when William Henry Harrison dies.

1844

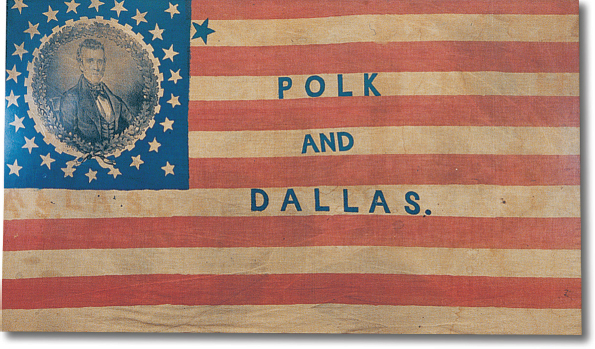

- – James K. Polk is elected president.

1845

- – Texas enters Union as slave state.

1846

- – Congress declares war on Mexico.

- – United States and Great Britain divide Oregon Country.

1848

- – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

1849

- – California gold rush begins.

ALTHOUGH EMIGRANTS ACTED as the advance guard of American empire, there was nothing automatic about the U.S. annexation of territory in the West. Acquiring territory required political action. In the 1840s, the politics of expansion became entangled with sectionalism and the slavery question. Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican borderlands also thrust the United States into dangerous diplomatic crises with Great Britain and Mexico.

Aggravation between Mexico and the United States escalated to open antagonism in 1845 when the United States annexed Texas. Absorbing territory still claimed by Mexico set the stage for war. But it was President James K. Polk’s insistence on having Mexico’s other northern provinces that made war certain. The war was not as easy as Polk anticipated, but it ended in American victory and the acquisition of a new American West. The discovery of gold in one of the nation’s new territories, California, prompted a massive wave of emigration that nearly destroyed Native American and Californio society.