How did the war for union become a fight for black freedom?

Printed Page 438

CHRONOLOGY

1861

- – First Confiscation Act.

1862

- – Second Confiscation Act.

- – Militia Act.

1863

- – Emancipation Proclamation is issued.

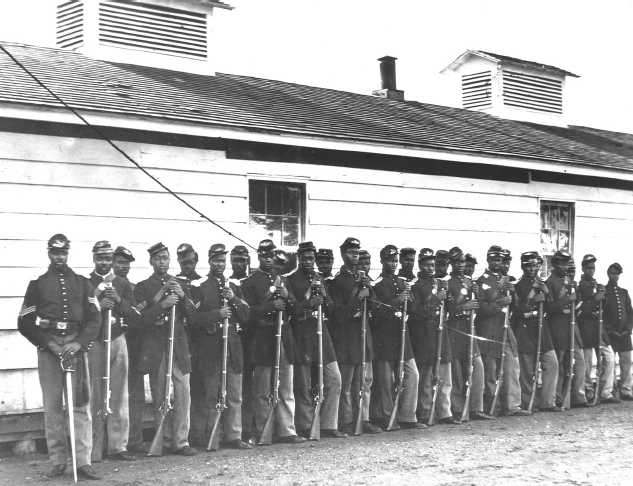

FOR A YEAR AND A HALF, Lincoln insisted that the North fought strictly to save the Union and not to abolish slavery. Nevertheless, the war for union became a war for African American freedom. Each month the conflict dragged on, it became clearer that the Confederate war machine depended heavily on slavery. Rebel armies used slaves to build fortifications, haul materiel, tend horses, and perform camp chores. On the southern home front, slaves labored in ironworks and shipyards, and they grew the food that fed both soldiers and civilians. Slavery undergirded the Confederacy as certainly as it had the Old South. Union military commanders and politicians alike gradually realized that to defeat the Confederacy, the North would have to destroy slavery. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation began the work, and soon African Americans flooded into the Union army, where they fought against the Confederacy and for black freedom.