Grant’s Troubled Presidency

Printed Page 476

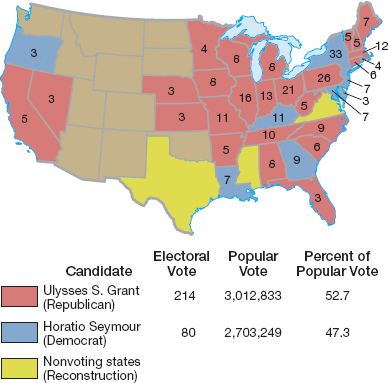

In 1868, the Republican Party’s presidential nomination went to Ulysses S. Grant, the North’s favorite general. His Democratic opponent, Horatio Seymour of New York, ran on a platform that blasted reconstruction as “a flagrant usurpation of power … unconstitutional, revolutionary, and void.” The Republicans answered by “waving the bloody shirt” — that is, they reminded voters that the Democrats were “the party of rebellion.” Grant gained a narrow 309,000-vote margin in the popular vote and a substantial victory (214 votes to 80) in the electoral college (Map 16.2).

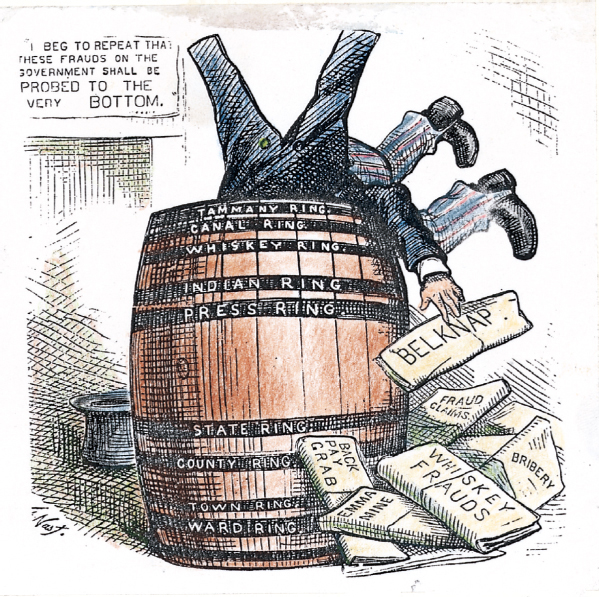

Grant was not as good a president as he was a general. The talents he had demonstrated on the battlefield — decisiveness, clarity, and resolution — were less obvious in the White House. Grant sought both justice for blacks and sectional reconciliation. But he surrounded himself with fumbling kinfolk and old friends from his army days and made a string of dubious appointments that led to a series of damaging scandals. Charges of corruption tainted his vice president, Schuyler Colfax, and brought down two of his cabinet officers. Though never personally implicated in any scandal, Grant was aggravatingly naive and blind to the rot that filled his administration.

In 1872, anti-Grant Republicans bolted and launched the Liberal Party. To clean up the graft and corruption, Liberals proposed ending the spoils system, by which victorious parties rewarded loyal workers with public office, and replacing it with a nonpartisan civil service commission that would oversee competitive examinations for appointment to office. Liberals also demanded that the federal government remove its troops from the South and restore “home rule” (southern white control). Democrats liked the Liberals’ southern policy and endorsed the Liberal presidential candidate, Horace Greeley, the longtime editor of the New York Tribune. The nation, however, still felt enormous affection for the man who had saved the Union and reelected Grant with 56 percent of the popular vote.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

Why did Congress object to Lincoln’s wartime plan for reconstruction?

How did the North respond to the passage of black codes in the southern states?

How radical was congressional reconstruction?

What brought the elements of the South’s Republican coalition together?

Why did reconstruction collapse?

Conclusion: Was reconstruction “a revolution but half accomplished”?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.