What did U.S. expansion mean for Native Americans?

Printed Page 488

CHRONOLOGY

1851

- – First Treaty of Fort Laramie.

1862

- – Great Sioux Uprising (Santee Uprising).

1864

- – Sand Creek massacre.

1867

- – Treaty of Medicine Lodge.

1868

- – Second Treaty of Fort Laramie.

1870

- – Hunters begin to decimate bison herds.

1874

- – Gold is discovered in Black Hills.

1876

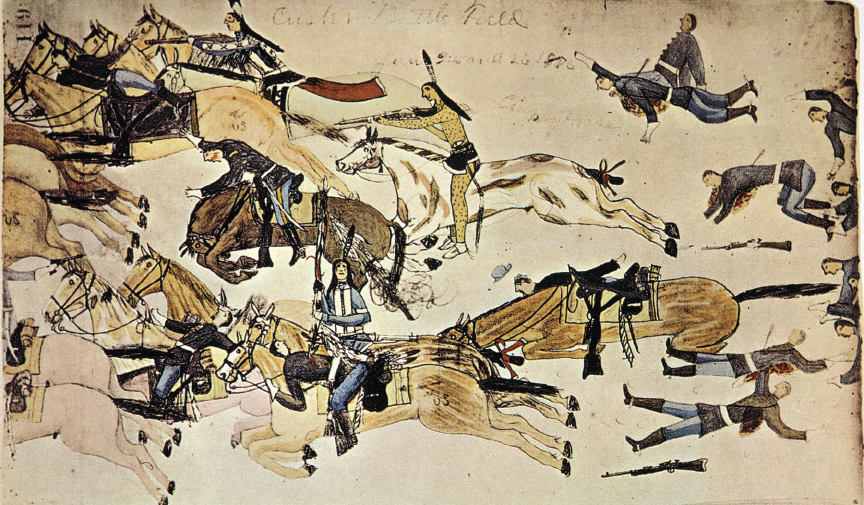

- – Battle of the Little Big Horn.

1881

- – Sitting Bull surrenders.

1893

- – Frederick Jackson Turner presents “frontier thesis.”

WHILE THE EUROPEAN POWERS expanded their authority and wealth through imperialism and colonialism in far-flung empires abroad, the United States focused its attention on the West. From the U.S. Army attack on the remainder of the Comanche empire to the conquest of the Black Hills, whites pushed Indians aside as they moved west. As posited by historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893, American exceptionalism derived from the ways in which the history of the United States differed from that of European nations, and he cited America’s western frontier as a cause. In what has become known as Turner’s “frontier thesis,” the availability of land provided a “safety valve,” releasing social tensions and providing opportunities for social mobility for Americans. Yet expansion in the trans-Mississippi West involved the conquest, displacement, and rule over native peoples — a process best understood in the global context of imperialism and colonialism.

The U.S. government, through trickery and conquest, pushed the Indians off their lands (Map 17.1) and onto designated Indian territories or reservations. The Indian wars that followed the Civil War depleted the Native American population and handed the lion’s share of Indian land over to white settlers. The decimation of the bison herds pushed the Plains Indians onto reservations, where they lived as wards of the state. Through the lens of colonialism, we can see how the United States, with its commitment to an imperialist, expansionist ideology, colonized the West.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

What did U.S. expansion mean for Native Americans?

In what ways did different Indian groups defy and resist colonial rule?

How did mining shape American expansion?

How did the fight for land and resources in the West unfold?

Conclusion: How did the West set the tone for the Gilded Age?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.