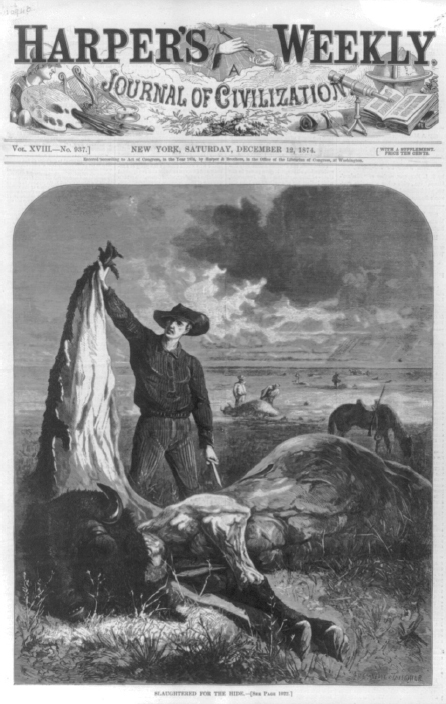

The Decimation of the Great Bison Herds

Printed Page 491

After the Civil War, the accelerating pace of industrial expansion brought about the near extinction of the American bison (buffalo). The development of larger, more accurate rifles combined with the growth of the nation’s transcontinental rail system, which cut the range in two and divided the herds, hastened the bison’s decline. For the Sioux and other nomadic tribes of the plains, the buffalo constituted a way of life — a source of food, fuel, and shelter and a central part of their religion and rituals. To the railroads, the buffalo were a nuisance, at best a cheap source of meat for their workers and a target for sport. “It will not be long before all the buffaloes are extinct near and between the railroads,” Ohio senator John Sherman predicted in 1868.

The decimation of the great bison herds contributed to the army’s conquest of the Plains Indians. General Philip Sheridan acknowledged as much when he applauded white hide hunters for “destroying the Indians’ commissary.” With their food supply gone, Indians had to choose between starvation and the reservation. “A cold wind blew across the prairie when the last buffalo fell,” the great Sioux leader Sitting Bull lamented, “a death wind for my people.”

On the southern plains in 1867, more than five thousand warring Comanches, Kiowas, and Southern Arapahos gathered at Medicine Lodge Creek in Kansas to negotiate the Treaty of Medicine Lodge. They sought to preserve limited land and hunting by moving the tribe to a reservation. Three years later, hide hunters poured into the region, and within a decade they had nearly exterminated the southern bison herds. Luther Standing Bear recounted the sight and stench: “I saw the bodies of hundreds of dead buffalo lying about, just wasting, and the odor was terrible… . They were letting our food lie on the plains to rot.” With the buffalo gone, the Indians faced starvation and became dependent on the stingy allotments provided on the reservations.