Andrew Carnegie, Steel, and Vertical Integration

Printed Page 521

If Jay Gould was the man Americans loved to hate, Andrew Carnegie became one of America’s heroes. Unlike Gould, Carnegie turned his back on speculation and worked to build something enduring — Carnegie Steel, the biggest steel business in the world during the Gilded Age.

The growth of the steel industry proceeded directly from railroad building. The first railroads ran on iron rails, which cracked and broke with alarming frequency. Steel, both stronger and more flexible than iron, remained too expensive for use in rails until Englishman Henry Bessemer developed a way to make steel more cheaply. Andrew Carnegie, among the first to champion the new “King Steel,” came to dominate the emerging industry.

Carnegie, a Scottish immigrant, landed in New York in 1848 at the age of twelve. He rose from a job cleaning bobbins in a textile factory to become one of the richest men in America. Before he died, he gave away more than $300 million, most notably to public libraries. His generosity, combined with his own rise from poverty, burnished his public image.

While Carnegie was a teenager, his skill as a telegraph operator caught the attention of Tom Scott, superintendent of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott hired Carnegie, soon promoted him, and lent him the money for his first foray into Wall Street investment. As a result of this crony capitalism, Carnegie became a millionaire before his thirtieth birthday. At that point, Carnegie turned away from speculation. “My preference was always manufacturing,” he wrote. “I wished to make something tangible.” By applying the lessons of cost accounting and efficiency that he had learned with the Pennsylvania Railroad, Carnegie turned steel into the nation’s first manufacturing big business (Figure 18.2).

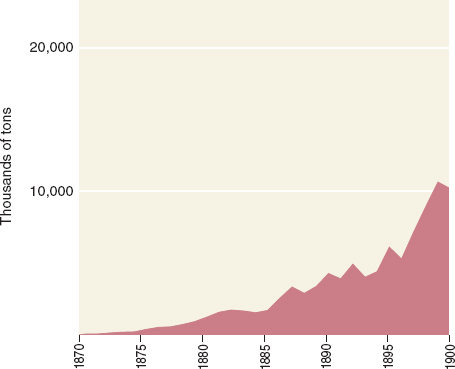

In 1872, Andrew Carnegie built the world’s largest, most up-to-date steel mill in Braddock, Pennsylvania. At that time, steelmakers produced about 70 tons a week. Within two decades, Carnegie’s blast furnaces poured out an incredible 10,000 tons a week. His formula for success was simple: “Cut the prices, scoop the market, run the mills full; watch the costs and profits will take care of themselves.” Carnegie pioneered a system of business organization called vertical integration, in which all aspects of the business were under Carnegie’s control — from the mining of iron ore, to its transport on the Great Lakes, to the production of steel. As one observer noted, “There was never a price, profit, or royalty paid to any outsider.”

The great productivity Carnegie encouraged came at a high price. He deliberately pitted his managers against one another, firing the losers and rewarding the winners with a share in the company. Workers achieved the output Carnegie demanded by enduring low wages, dangerous working conditions, and twelve-hour days six days a week. One worker, observing the contradiction between Carnegie’s generous endowment of public libraries and his labor policy, observed, “After working twelve hours, how can a man go to a library?”

By 1900, Andrew Carnegie had become the best-known manufacturer in the nation, and the age of iron had yielded to an age of steel. Steel from Carnegie’s mills supported the elevated trains in New York and Chicago, formed the skeleton of the Washington Monument, supported the first steel bridge to span the Mississippi, and girded America’s first skyscrapers. As a captain of industry, Carnegie’s only rival was the titan of the oil industry, John D. Rockefeller.