The Social Geography of the City

Printed Page 554

During the Gilded Age, the social geography of the city changed enormously. Cleveland, Ohio, provides a good example. In the 1870s, Cleveland was a small city in both population and area. Oil magnate John D. Rockefeller could, and often did, walk from his large brick house on Euclid Avenue to his office downtown. On his way, he passed the small homes of his clerks and other middle-class families. Behind these homes ran miles of alleys crowded with the dwellings of Cleveland’s working class. Farther out, on the shores of Lake Erie, close to the factories and foundries, clustered the shanties of the city’s poorest laborers.

Within two decades, the Cleveland that Rockefeller knew no longer existed. The coming of mass transit transformed the walking city. In its place emerged a central business district surrounded by concentric rings of residences organized by ethnicity and income. First the horsecar in the 1870s and then the electric streetcar in the 1880s made it possible for those who could afford the five-cent fare to work downtown and flee after work to the “cool green rim” of the city. Social segregation — the separation of rich and poor, and of recent immigrants and old-stock Americans — became one of the major social changes engendered by the rise of the industrial metropolis.

Race and ethnicity affected the way cities evolved. Newcomers to the nation’s cities faced hostility and not surprisingly sought out their kin and country folk as they struggled to survive. Distinct ethnic neighborhoods often formed around a synagogue or church. African Americans typically experienced the greatest residential segregation, but every large city had its ethnic enclaves — Little Italy, Chinatown, Bohemia Flats, Germantown — where English was rarely spoken.

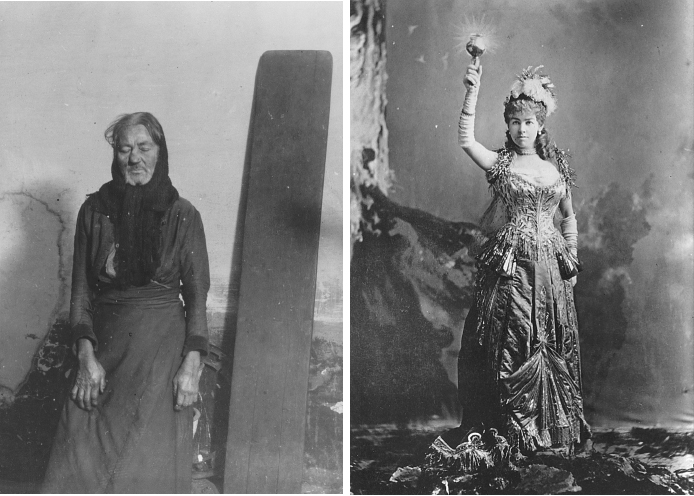

Poverty, crowding, dirt, and disease constituted the daily reality of New York City’s immigrant poor — a plight documented by photojournalist Jacob Riis in his best-selling book How the Other Half Lives (1890). By taking his camera into the hovels of the poor, Riis opened the nation’s eyes to conditions in the city’s slums.

While Riis’s audience shivered at his revelations about the “other half,” many middle-class Americans worried equally about the excesses of the wealthy. They feared the class antagonism fueled by the growing chasm between rich and poor and shared Riis’s view that “the real danger to society comes not only from the tenements, but from the ill-spent wealth which reared them.”

The excesses of the Gilded Age’s newly minted millionaires were nowhere more visible than in the lifestyle of the Vanderbilts. Alva Vanderbilt launched herself into New York society in 1883 with a costume party so opulent that her sister-in-law Alice Vanderbilt appeared as that miraculous new invention, the electric light, resplendent in a white satin evening dress studded with diamonds.

Such ostentatious displays of wealth became especially alarming when they were coupled with disdain for the well-being of ordinary people. When a reporter in 1882 asked William Vanderbilt whether he considered the public good when running his railroads, he shot back, “The public be damned.” The fear that America had become a plutocracy — a society ruled by the rich — gained credence from the fact that the wealthiest 1 percent of the population owned more than half the real and personal property in the country. As the new century dawned, reformers would form a progressive movement to address the problems of urban industrialism and the substandard living and working conditions it produced.

QUICK REVIEW

Question

What global trends were reflected in the growth of America’s cities in the late nineteenth century?

Why did American cities experience explosive growth in the late nineteenth century?

What kinds of work did people do in industrial America?

Why did the fortunes of the Knights of Labor rise in the late 1870s and decline in the 1890s?

How did urban industrialism shape home life and the world of leisure?

How did municipal governments respond to the challenges of urban expansion?

Conclusion: Who built the cities?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.