The Farmers’ Alliance

Printed Page 580

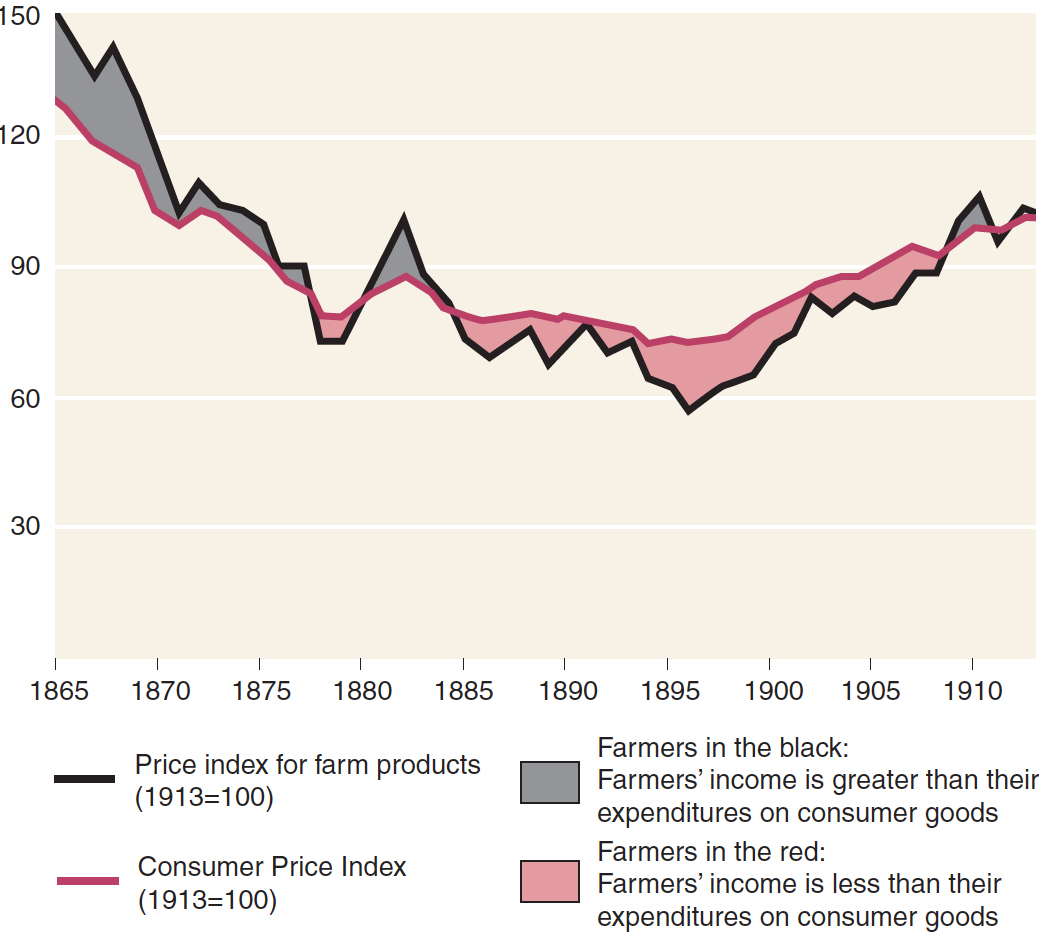

At the heart of the farmers' problems stood a banking system dominated by eastern commercial banks committed to the gold standard, a railroad rate system both capricious and unfair, and rampant speculation that drove up the price of land. In the West, farmers rankled under a system that allowed railroads to charge them exorbitant freight rates while granting rebates to large shippers (see "Railroads: America's First Big Business" in chapter 18). In the South, lack of currency and credit drove farmers to the stopgap credit system of the crop lien. Determined to do something, farmers banded together to fight for change.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

Why did American farmers organize alliances in the late nineteenth century?

What led to the labor wars of the 1890s?

How were women involved in late-nineteenth-century politics?

How did economic problems affect American politics in the 1890s?

Why did the United States largely abandon its isolationist foreign policy in the 1890s?

Conclusion: What was the connection between domestic strife and foreign policy?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.

Farm protest was not new. In the 1870s, farmers had supported the Grange and the Greenback Labor Party. As the farmers’ situation grew more desperate, they organized, forming regional alliances. The first Farmers' Alliance came together in 1876 in Lampasas County, Texas, to fight “landsharks and horse thieves.” In frontier farmhouses in Texas, in log cabins in the backwoods of Arkansas, and in the rural parishes of Louisiana, separate groups of farmers formed similar alliances for self-help.

Movement to form local organizations to advance farmers’ collective interests that gained popularity in the 1880s. Over time, farmers’ groups consolidated into two regional alliances: the Northwestern Farmers’ Alliance and the Southern Farmers’ Alliance. In 1892, the Farmers’ Alliance gave birth to the People's Party and launched the Populist movement.

Movement to form local organizations to advance farmers’ collective interests that gained popularity in the 1880s. Over time, farmers’ groups consolidated into two regional alliances: the Northwestern Farmers’ Alliance and the Southern Farmers’ Alliance. In 1892, the Farmers’ Alliance gave birth to the People's Party and launched the Populist movement.

As the movement grew in the 1880s, farmers’ groups consolidated into two regional alliances: the Northwestern Farmers’ Alliance, active in Kansas, Nebraska, and other midwestern Granger states; and the more radical Southern Farmers’ Alliance. Traveling lecturers preached the Alliance message. Worn-out men and careworn women did not need to be convinced that something was wrong. By 1890, the Southern Farmers’ Alliance alone counted more than three million members.

Radical in its inclusiveness, the Southern Alliance reached out to African Americans, women, and industrial workers. Through cooperation with the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, an African American group founded in Texas in the 1880s, blacks and whites attempted to make common cause. As Georgia’s Tom Watson, a Southern Alliance stalwart, pointed out, “The colored tenant is in the same boat as the white tenant, … and … the accident of color can make no difference in the interests of farmers, croppers, and laborers.” Women rallied to the Alliance banner. “I am going to work for prohibition, the Alliance, and for Jesus as long as I live,” swore one woman.

At the heart of the Alliance movement stood a series of farmers’ cooperatives. By “bulking” their cotton — that is, selling it together — farmers could negotiate a better price. And by setting up trade stores and exchanges, they sought to escape the grasp of the merchant/creditor. Through the cooperatives, the Farmers’ Alliance promised to change the way farmers lived. “We are going to get out of debt and be free and independent people once more,” exulted one Georgia farmer. But the Alliance faced insurmountable difficulties in running successful cooperatives. Opposition by merchants, bankers, wholesalers, and manufacturers made it impossible for the cooperatives to get credit. As the cooperative movement died, the Farmers’ Alliance moved into politics.