The Great Migrations of African Americans and Mexicans

Printed Page 670

Before the Red scare lost steam, the government raised alarms about the loyalty of African Americans. A Justice Department investigation concluded that Reds were fomenting racial unrest among blacks. Although the report was wrong about Bolshevik influence, it was correct in noticing a new stirring among African Americans.

In 1900, nine of every ten blacks still lived in the South, where poverty, disfranchisement, segregation, and violence dominated their lives. Whites remained committed to keeping blacks down. “If we own a good farm or horse, or cow, or bird-dog, or yoke of oxen,” a black sharecropper in Mississippi observed in 1913, “we are harassed until we are bound to sell, give away, or run away, before we can have any peace in our lives.”

The First World War provided African Americans with the opportunity to escape the South’s cotton fields and kitchens. When war channeled almost 5 million American workers into military service and almost ended European immigration, northern industrialists turned to black labor. Black men found work in northern steel mills, shipyards, munitions plants, railroad yards, automobile factories, and mines. From 1915 to 1920, half a million blacks (approximately 10 percent of the South’s black population) boarded trains bound for Philadelphia, Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, and other industrial cities.

Thousands of migrants wrote home to tell family and friends about their experiences in the North. One man announced proudly that he had recently been promoted to “first assistant to the head carpenter.” He added, “I should have been here twenty years ago. I just begin to feel like a man. … My children are going to the same school with the whites and I don’t have to [h]umble to no one. I have registered — will vote the next election and there ain’t any ‘yes sir’ — it’s all yes and no and Sam and Bill.”

But the North was not the promised land. Black men stood on the lowest rungs of the labor ladder. Jobs of any kind proved scarce for black women, and most worked as domestic servants as they did in the South. The existing black middle class sometimes shunned the less educated, less sophisticated rural southerners crowding into northern cities. Many whites, fearful of losing jobs and status, lashed out against the new migrants. Savage race riots ripped through two dozen northern cities. In 1918, the nation witnessed ninety-six lynchings of blacks, some of them decorated war veterans still in uniform.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

What was Woodrow Wilson’s foreign policy agenda?

What role did the United States play in World War I?

What impact did the war have on the home front?

What part did Woodrow Wilson play at the Paris peace conference?

Why was America’s transition from war to peace so turbulent?

Conclusion: What was the domestic cost of foreign victory?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.

Still, most black migrants stayed in the North and encouraged friends and family to follow. By 1940, more than one million blacks had left the South, profoundly changing their own lives and the course of the nation’s history. Black enclaves such as Harlem in New York and the South Side of Chicago, “cities within cities,” emerged in the North. These assertive communities provided a foundation for black protest and political organization in the years ahead.

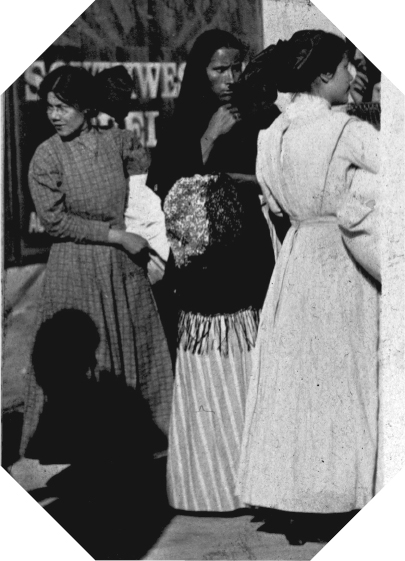

At nearly the same time, another migration was under way in the American Southwest. Between 1910 and 1920, the Mexican-born population in the United States soared from 222,000 to 478,000. Mexican immigration resulted from developments on both sides of the border. When Mexicans revolted against dictator Porfirio Díaz in 1910, initiating a ten-year civil war, migrants flooded northward. In the United States, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and later the disruption of World War I cut off the supply of cheap foreign labor and caused western employers in the expanding rail, mining, construction, and agricultural industries to look south to Mexico for workers.

Like immigrants from Europe and black migrants from the South, Mexicans in the American Southwest dreamed of a better life. And like the others, they found both opportunity and disappointment. Wages were better than in Mexico, but life in the fields, mines, and factories was hard, and living conditions — in boxcars, labor camps, or urban barrios — were dismal. Signs warning “No Mexicans Allowed” increased rather than declined. Mexicans were considered excellent prospects for manual labor but not for citizenship. Among Mexican Americans, some of whom had lived in the Southwest for more than a century, los recién llegados (the recent arrivals) encountered mixed reactions. One Mexican American expressed this ambivalence: “We are all Mexicans anyway because the gueros [Anglos] treat us all alike.” But he also called for immigration quotas because the recent arrivals drove down wages and incited white prejudice that affected all Mexican Americans.

Despite friction, large-scale immigration into the Southwest meant a resurgence of the Mexican cultural presence, which became the basis for greater solidarity and political action for the ethnic Mexican population. In 1929 in Texas, Mexican Americans formed the League of United Latin American Citizens.