Modern Republicanism

Printed Page 806

In contrast to the old guard conservatives in his party who criticized containment and wanted to repeal much of the New Deal, Dwight D. Eisenhower preached “modern Republicanism.” This meant resisting additional federal intervention in economic and social life but not turning the clock back to the 1920s. Democratic control of Congress after the elections of 1954 further contributed to Eisenhower’s moderate approach.

The new president attempted to distance himself from the anti-Communist fervor that had plagued the Truman administration, even as he intensified Truman’s loyalty program, allowing federal executives to dismiss thousands of employees on grounds of loyalty, security, or “suitability.” Reflecting his inclination to avoid controversial issues, Eisenhower refused to denounce Senator Joseph McCarthy publicly. In 1954, McCarthy began to destroy himself when he hurled reckless charges of communism against military personnel during televised hearings. When the army’s lawyer demanded of McCarthy, “Have you left no sense of decency?” those in the hearing room applauded. In 1954, the Senate voted to condemn him, marking the end of his influence but not the end of pursuing radicals.

Eisenhower sometimes echoed the conservative Republicans’ conviction that government was best left to the states and economic decisions to private business. Yet he signed laws bringing ten million more workers under Social Security, increasing the minimum wage, and creating a new Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. And when the spread of polio neared epidemic proportions, Eisenhower obtained funds from Congress to distribute a vaccine, even though conservatives wanted to leave that responsibility to the states.

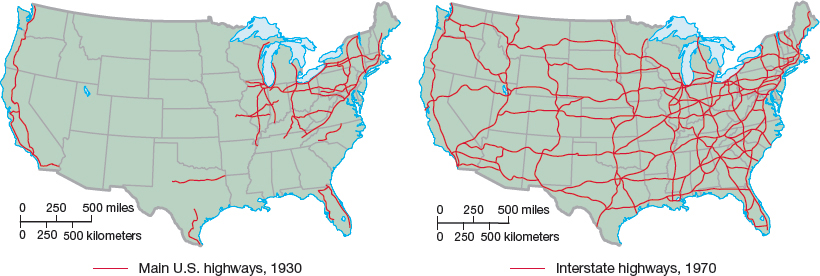

Eisenhower’s greatest domestic initiative was the Interstate Highway and Defense System Act of 1956 (Map 27.1). Promoted as essential to national defense and an impetus to economic growth, the act authorized construction of a national highway system, with the federal government paying most of the costs through increased fuel and vehicle taxes. The new highways accelerated the mobility of people and goods, and they benefited the trucking, construction, and automobile industries, which had lobbied hard for the law. Eventually, the monumental highway project exacted such unforeseen costs as air pollution, increased energy consumption, declining railroads and mass transportation, and the decay of central cities.

Law authorizing the construction of a national highway system. Promoted as essential to national defense and an impetus to economic growth, the national highway system accelerated the movement of people and goods and changed the nature of American communities.

Law authorizing the construction of a national highway system. Promoted as essential to national defense and an impetus to economic growth, the national highway system accelerated the movement of people and goods and changed the nature of American communities.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

What was Eisenhower’s “middle way” on domestic issues?

How did Eisenhower’s foreign policy differ from Truman’s?

What fueled the prosperity of the 1950s?

How did prosperity affect American society and culture?

How did African Americans fight for civil rights in the 1950s?

Conclusion: What unmet challenges did peace and prosperity mask?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.

In other areas, Eisenhower restrained federal activity in favor of state governments and private enterprise. His large tax cuts directed most benefits to business and the wealthy, and he resisted federal aid to primary and secondary education as well as strong White House leadership on behalf of civil rights. Eisenhower opposed national health insurance, preferring the growing practice of private insurance provided by employers. Although Democrats sought to keep nuclear power in government hands, Eisenhower signed legislation authorizing the private manufacture and sale of nuclear energy.