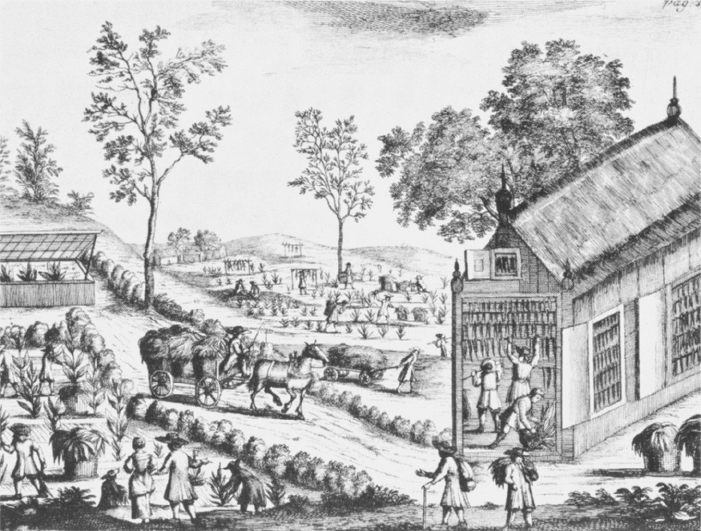

Tobacco Agriculture

Printed Page 61

Initially, the Virginia Company had no plans to grow and sell tobacco. John Rolfe — future husband of Pocahontas — planted West Indian tobacco seeds in 1612 and learned that they flourished in Virginia. By 1617, the colonists had grown enough tobacco to send the first commercial shipment to England, where it sold for a high price. After that, Virginia pivoted from a colony of rather aimless adventurers to a society of dedicated tobacco planters.

A demanding crop, tobacco required close attention and a great deal of hand labor year-round. Like the Indians, the colonists “cleared” fields by cutting a ring of bark from each tree (a procedure known as “girdling”), thereby killing the tree. Girdling brought sunlight to clearings but left fields studded with tree stumps, requiring colonists to use heavy hoes to till their tobacco fields. To plant, a visitor observed, they “just make holes [with a stick] into which they drop the seeds,” much as the Indians did.

The English settlers worked hard because their labor promised greater rewards in the Chesapeake region than in England. One colonist proclaimed that “the dirt of this Province affords as great a profit to the general Inhabitant, as the Gold of Peru doth to … the Spaniard.” Although he exaggerated, it was true that a hired man could expect to earn two or three times more in Virginia’s tobacco fields than in England. Better still, in Virginia land was so abundant that it was extremely cheap compared with land in England.

CHAPTER LOCATOR

What challenges faced early Chesapeake colonists?

How did Chesapeake tobacco society take shape?

Why did Chesapeake colonial society change in the late seventeenth century?

Why did the southern colonies move toward a slave labor system?

Conclusion: Why were export crops and slave labor important in the growth of the southern colonies?

LearningCurve

LearningCurve

Check what you know.

By the mid-seventeenth century, common laborers could buy a hundred acres for less than their annual wages — an impossibility in England. New settlers who paid their own transportation to the Chesapeake received a grant of fifty acres of free land (termed a headright). The Virginia Company granted headrights to encourage settlement, and the royal government continued them for the same reason.

Fifty acres of free land granted by the Virginia Company to new settlers who paid their own transportation to the Chesapeake and to planters for each indentured servant they purchased.

Fifty acres of free land granted by the Virginia Company to new settlers who paid their own transportation to the Chesapeake and to planters for each indentured servant they purchased.