How did partisan rivalries shape the politics of the late 1790s?

Printed Page 253

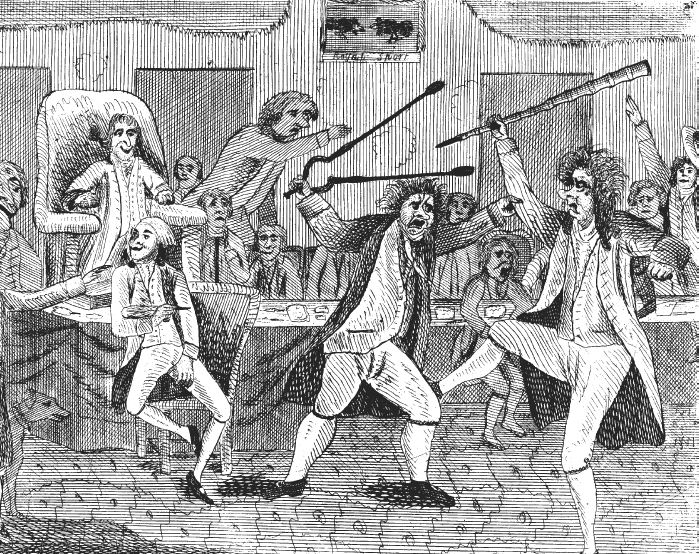

BY THE MID-1790s, polarization over the French Revolution, Haiti, the Jay Treaty, and Hamilton’s economic plans had led to two distinct and consistent rival political groups: Federalists and Republicans. Federalist leaders supported Britain in foreign policy and commercial interests at home, while Republicans rooted for liberty in France and worried about monarchical Federalists at home. The labels did not yet describe full-fledged political parties; such division was still thought to be a sign of failure of the experiment in government. Washington’s decision not to seek a third term led to serious partisan electioneering in the presidential and congressional elections of 1796. Federalist John Adams won the presidency, but party strife accelerated over failed diplomacy in France, bringing the country to the brink of war. Pro-war and antiwar antagonism created a major crisis over political free speech, militarism, and fears of sedition and treason.

CHRONOLOGY

1796

- – John Adams is elected president.

1797

- – XYZ affair.

1798

- – Quasi-War with France erupts.

- – Alien and Sedition Acts.

- – Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions.

1800

- – Thomas Jefferson is elected president.

Originally the term for the supporters of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1787–1788. In the 1790s, it became the name for one of the two dominant political groups that emerged during that decade. Federalist leaders of the 1790s supported Britain in foreign policy and commercial interests at home. Prominent Federalists included George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams.

Originally the term for the supporters of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1787–1788. In the 1790s, it became the name for one of the two dominant political groups that emerged during that decade. Federalist leaders of the 1790s supported Britain in foreign policy and commercial interests at home. Prominent Federalists included George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and John Adams.

One of the two dominant political groups that emerged in the 1790s. Republicans supported the revolutionaries in France and worried about monarchical Federalists at home. Prominent Republicans included Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

One of the two dominant political groups that emerged in the 1790s. Republicans supported the revolutionaries in France and worried about monarchical Federalists at home. Prominent Republicans included Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.