Washington City Burns: The British Offensive

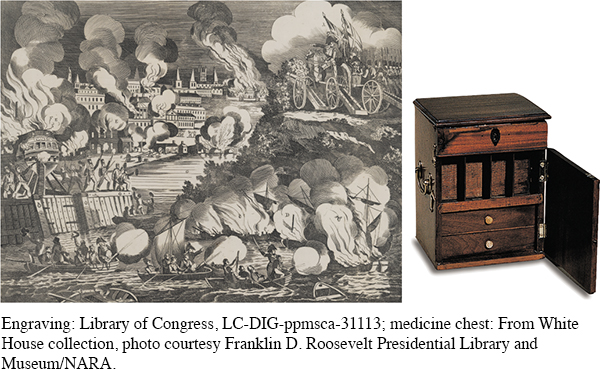

In August 1814, British ships sailed into Chesapeake Bay, landing 5,000 troops and throwing the capital into a panic. Families evacuated, banks hid their money, and government clerks carted away boxes of important papers. Dolley Madison, with dinner for guests cooking over the fire, fled with her husband’s papers, while servants rescued a portrait of George Washington. As the cook related, “When the British did arrive, they ate up the very dinner, and drank the wines, &c., that I had prepared for the President’s party.” Then the British torched the White House, the Capitol, a newspaper office, and a well-stocked arsenal. Instead of trying to hold the city, the British headed north and attacked Baltimore, but a fierce defense by the Maryland militia thwarted that effort.

In another powerful offensive that same month, British troops marched from Canada into New York State, but a series of mistakes cost them a naval skirmish at Plattsburgh on Lake Champlain, and they retreated to Canada. Five months later, another large British army landed in lower Louisiana and, in early January 1815, encountered General Andrew Jackson and his militia just outside New Orleans. Jackson’s forces carried the day. The British suffered between 2,000 and 3,000 casualties, the Americans fewer than 80. Jackson instantly became known as the hero of the battle of New Orleans. No one in the United States knew that negotiators in Europe had signed a peace agreement two weeks earlier. [[LP Photo: P10.06 The Burning of Washington City/

The Treaty of Ghent, signed in December 1814, settled few of the surface issues that had led to war. Neither country could claim victory, and no land changed hands. Instead, the treaty reflected a mutual agreement to give up certain goals. The Americans dropped their plea for an end to impressment, which in any case subsided as soon as Britain and France ended their war in 1815. They also gave up any claim to Canada. The British agreed to stop all aid to the Indians. Nothing was said about shipping rights. The most concrete result was a plan for a future commission to determine the exact boundary between the United States and Canada.

Antiwar Federalists in New England could not gloat over the war’s ambiguous conclusion because of an ill-timed and seemingly unpatriotic move on their part. The region’s leaders had convened a secret meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, in December 1814 to discuss a series of proposals aimed at reducing the South’s power and breaking Virginia’s lock on the presidency. They proposed abolishing the Constitution’s three-fifths clause as a basis of representation; requiring a two-thirds vote instead of a simple majority for imposing embargoes, admitting states, or declaring war; limiting the president to one term; and prohibiting the election of successive presidents from the same state. They even discussed secession from the Union but rejected that path. Coming just as peace was achieved, however, the Hartford Convention looked very unpatriotic. The Federalist Party never recovered, and within a few years it was reduced to a shadow of its former self, even in New England.

No one really won the War of 1812; however, Americans celebrated as though they had, with parades and fireworks. The war gave rise to a new spirit of nationalism. The paranoia over British tyranny evident in the 1812 declaration of war was laid to rest, replaced by pride in a more equal relationship with the old mother country. Indeed, in 1817 the two countries signed the Rush-Bagot disarmament treaty (named after its two negotiators), which limited each country to a total of four naval vessels, each with just a single cannon, to patrol the vast watery border between them. It was the most successful disarmament treaty for a century to come.

The biggest winners in the War of 1812 were the young men, once called War Hawks, who took up the banner of the Republican Party and carried it in new, expansive directions. These young politicians favored trade, western expansion, internal improvements, and the energetic development of new economic markets. The biggest losers of the war were the Indians. Tecumseh was dead, his brother the Prophet was discredited, the prospects of an Indian confederacy were dashed, the Creek’s large homeland was seized, and the British protectors were gone.

> QUICK REVIEW

Was the War of 1812 inevitable? Why or why not?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 268

Section Chronology