Factories, Workingwomen, and Wage Labor

Transportation advances accelerated manufacturing after 1815, creating an ever-expanding market for goods. The two leading industries, textiles and shoes, altered methods of production and labor relations. Textile production was greatly spurred by the development of water-driven machinery built near fast-coursing rivers. Shoe manufacturing, still using the power and skill of human hands, involved only a reorganization of production. Both industries pulled young women into wage-earning labor for the first time.

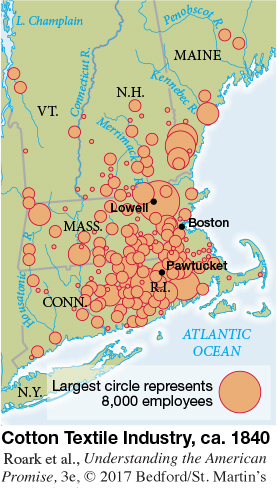

The earliest American textile factory was built in the 1790s by an English immigrant in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. By 1815, nearly 170 spinning mills stood along New England rivers. While British manufacturers hired entire families for mill work, American factory owners innovated by hiring young women, assumed to be cheap to hire because of their limited employment options and their short-term prospects, since most left to get married. [[LP Spot Map: SM11.01 Cotton Textile Industry, ca. 1840/

In 1821, a group of Boston entrepreneurs founded the town of Lowell on the Merrimack River, centralizing all aspects of cloth production: combing, shrinking, spinning, weaving, and dyeing. By 1836, the eight Lowell mills employed more than five thousand young women, who lived in carefully managed company-owned boardinghouses. Corporation rules at the Lowell mills required church attendance and prohibited drinking and unsupervised courtship; dorms were locked at 10 p.m. A typical mill worker earned $2 to $3 for a seventy-hour week, more than a seamstress or domestic servant could earn but less than a young man’s wages.

Despite the long hours, young women embraced factory work as a means to earn spending money and build savings before marriage; several banks in town held the nest eggs of thousands of workers. Also welcome was the unprecedented, though still limited, personal freedom of living in an all-female social space, away from parents and domestic tasks. In the evening, the women could engage in self-improvement activities, such as attending public lectures. In 1837, 1,500 mill girls crowded Lowell’s city hall to hear the sisters Angelina and Sarah Grimké speak about the evils of slavery.

In the mid-1830s, worldwide growth and competition in the cotton market impelled mill owners to speed up work and decrease wages. The workers protested, emboldened by their communal living arrangement and by their relative independence as temporary employees. In 1834 and again in 1836, hundreds of women at Lowell went out on strike. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: Mill Girls Stand Up to Factory Owners, 1834.”) Such strikes spread; in 1834, mill workers in Dover, New Hampshire, denounced their owners for trying to turn them into “slaves.” Their assertiveness surprised many, but ultimately the ease of replacing them undermined their bargaining power, and owners in the 1840s began to shift to immigrant families as their primary labor source.

The shoe manufacturing industry centered in eastern New England reorganized production and hired women, including wives, as shoebinders. Male shoemakers still cut the leather and made the soles in shops, but female shoebinders working from home now stitched the upper parts of the shoes. Working from home meant that wives could contribute to family income—unusual for most wives in that period—and still perform their domestic chores.

In the economically turbulent 1830s, shoebinder wages fell. Unlike mill workers, female shoebinders worked in isolation, a serious hindrance to organized protest. In Lynn, Massachusetts, a major shoemaking center, women used female church networks to organize resistance, communicating via religious newspapers. The Lynn shoebinders who demanded higher wages in 1834 built on a collective sense of themselves as women. “Equal rights should be extended to all—to the weaker sex as well as the stronger,” they proclaimed.

> COMPARE AND CONTRAST

What did female textile workers have in common with female shoebinders, and how and why did their experiences in the workforce differ?

In the end, the Lynn shoebinders’ protests failed to achieve wage increases. At-home workers all over New England continued to accept low wages, and even in Lynn many women shied away from organized protest, preferring to situate their work in the context of family duty (helping their husbands to finish the shoes) instead of market relations.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 287

Section Chronology