Oregon and the Overland Trail

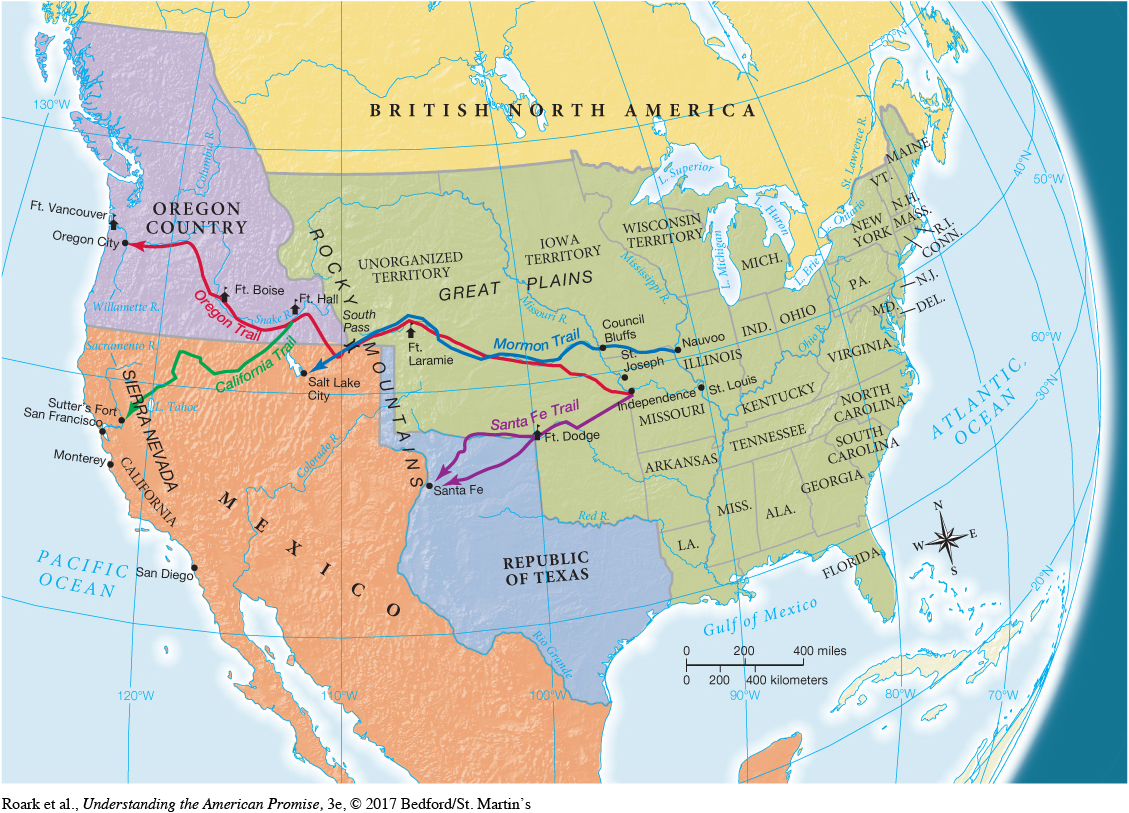

American expansionists and the British competed for the Oregon Country—a vast region bounded on the west by the Pacific Ocean, on the east by the Rocky Mountains, on the south by the forty-second parallel, and on the north by Russian Alaska. In 1818, the United States and Great Britain decided on “joint occupation” that would leave Oregon “free and open” to settlement by both countries. By the 1820s, a handful of American fur traders and “mountain men” roamed the region.

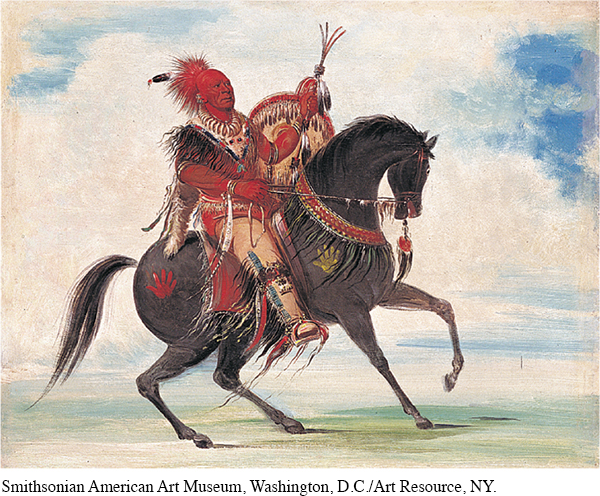

In the late 1830s, settlers began to trickle along the Oregon Trail, following a path blazed by the mountain men (Map 12.2). The first wagon trains headed west in 1841, and by 1843 about 1,000 emigrants a year set out from Independence, Missouri. By 1869, when the first transcontinental railroad was completed, approximately 350,000 migrants had traveled west in wagon trains. [[LP Photo: P12.05 Kee-O-Kuk, the Watchful Fox, Chief of the Tribe, by George Catlin, 1835/

[[LP Map: M12.02 Major Trails West /

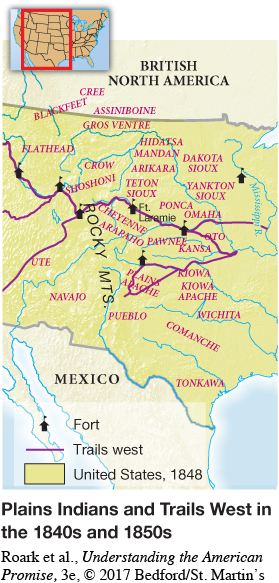

Emigrants encountered the Plains Indians, a quarter of a million Native Americans scattered over the area between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. Some were farmers who lived peaceful, sedentary lives, but a majority—the Sioux, Cheyenne, Shoshoni, and Arapaho of the central plains and the Kiowa, Wichita, and Comanche of the southern plains—were horse-mounted, nomadic, nonagricultural peoples whose warriors symbolized the “savage Indian” in the minds of whites.

Horses, which had been brought to North America by Spaniards in the sixteenth century, permitted the Plains tribes to become highly mobile hunters of buffalo. They came to depend on buffalo for nearly everything—food, clothing, shelter, and fuel. Competition for buffalo led to war between the tribes. Young men were introduced to warfare early, learning to ride ponies at breakneck speed while firing off arrows and, later, rifles with astounding accuracy. “A Comanche on his feet is out of his element,” observed western artist George Catlin, “but the moment he lays his hands upon his horse, his face even becomes handsome, and he gracefully flies away like a different being.”

The Plains Indians struck fear in the hearts of whites on the wagon trains. But Native Americans had far more to fear from whites. Indians killed fewer than four hundred emigrants on the trail between 1840 and 1860, while whites brought alcohol and deadly epidemics. Moreover, white hunters slaughtered buffalo for the international hide market and sometimes just for sport.

> CONSIDER CAUSE

AND EFFECT

What were the consequences of Americans’ westward migration for the Native American groups who lived west of the Mississippi River in the 1840s and 1850s?

The government constructed a chain of forts along the Oregon Trail (Map 12.2) and adopted a new Indian policy: “concentration.” In 1851, government negotiators at the Fort Laramie conference persuaded the Plains Indians to sign agreements that cleared a wide corridor for wagon trains by restricting Native Americans to specific areas that whites promised they would never violate. This policy of concentration became the seedbed for the subsequent policy of reservations. But whites would not keep out of Indian territory, and Indians would not easily give up their traditional ways of life. Struggle for control of the West meant warfare for decades to come.

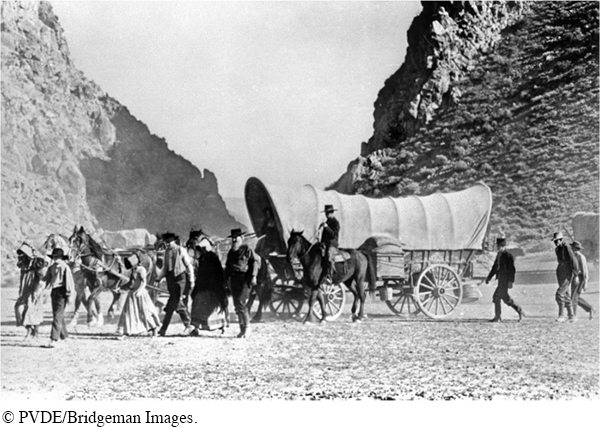

Still, Indians threatened emigrants less than life on the trail did. Emigrants could count on at least six months of grueling travel. With nearly two thousand miles to go and traveling no more than fifteen miles a day, the pioneers endured parching heat, drought, treacherous rivers, disease, physical and emotional exhaustion, and, if the snows closed the mountain passes before they got through, freezing and starvation. Women faced the ordeal of trailside childbirth. It was said that a person could walk from Missouri to the Pacific stepping only on the graves of those who had died heading west. [[LP Spot Map: SM12.01 Plains Indians and Trails West in the 1840s and 1850s/

Men usually found Oregon “one of the greatest countries in the world.” From “the Cascade mountains to the Pacific, the whole country can be cultivated,” exclaimed one eager settler. When women reached Oregon, they found that neighbors were scarce and things were in a “primitive state.” “I had all I could do to keep from asking George to turn around and bring me back home,” one woman wrote to her mother in Missouri. Work seemed unending. “I am a very old woman,” declared twenty-nine-year-old Sarah Everett. “My face is thin sunken and wrinkled, my hands bony withered and hard.” Another settler observed, “A woman that can not endure almost as much as a horse has no business here.” Yet despite the ordeal of the trail and the difficulties of starting from scratch, emigrants kept coming. [[LP Photo: P12.06 Pioneers Heading West/

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 323

Section Chronology